Assessing the Synergistic Anticancer impact of Metronidazole and Ciprofloxacin in Cervical Cancer: MAPK-RAS Pathway as a Key Mechanism

Download

Abstract

Objective: This study assessed the anticancer impact of the Metronidazole-Ciprofloxacin mixture, focusing on its molecular mechanism by examining its ability to target the Ras-MAPK signaling pathway.

Methods: The MTT assay evaluated the anticancer and safety properties of a Metronidazole-Ciprofloxacin mixture. HeLa cells and human-derived adipose tissue (NHF) cell lines were used in two incubations for 24 and 72 hours, with concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 1000 µg/ml for each treatment. Cisplatin was employed for comparative purposes. The combination index CI and the selective toxicity index SI were used to assess the possible synergistic effects of the mixture’s ingredients and selective toxicity. Computational molecular docking simulations were utilized to investigate the binding affinity of the mixture ingredients to various kinase signal proteins within the MAPK-RAS pathway.

Results: The MTT assay demonstrated that metronidazole, ciprofloxacin, cisplatin, and the mixture inhibit cervical cancer growth, with the mixture having a significantly greater impact than the others. The mixture showed a lesser effect on the viability of the NHF cell line and exhibited a favorable selectivity index compared to cisplatin. Additionally, the CI suggests that the medications act synergistically when used together. The molecular docking study revealed that the optimal interactions were between ciprofloxacin and RAS GTPase, and metronidazole and ERK2 kinase, with docking scores of -7.3 kcal/mol and -6.3 kcal/mol, respectively.

Conclusion: Regarding the study outcomes and the well-known pharmacokinetic and safety profiles of the mixture ingredients, the metronidazole-ciprofloxacin mixture presents an attractive and safer alternative for treating cervical cancer.

1. Introduction

Cervical cancer poses a considerable global health challenge, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where it is the fourth most prevalent cancer among women [1]. Chronic infections with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types, particularly HPV-16 and HPV-18, are the leading causes of about 70% of cases [2-4]. Although effective screening programs and HPV vaccinations are accessible, unequal access to these preventive measures results in higher incidence and mortality rates in low- and middle-income countries relative to high-income countries [3, 5, 6]. “Early cervical cancer detection through Pap smears and HPV testing has significantly reduced cancer rates in regions with robust healthcare systems.” [3, 7-10]. The primary treatment for cervical cancer is chemoradiotherapy. Chemotherapy, typically involving cisplatin-based regimens, faces notable challenges such as systemic toxicity, drug resistance, and adverse effects on healthy cell tissues [11]. Side effects such as nephrotoxicity, myelosuppression, and gastrointestinal distress frequently reduce patients’ quality of life and restrict the effectiveness of treatment options. [12].

The adverse effects linked to chemotherapy highlight the need for safer alternatives. Many trials have been undertaken to discover an effective treatment for cervical cancer by repurposing a drug created initially for different therapeutic uses rather than for cervical cancer [13-19]. Along with this aspect, metronidazole and ciprofloxacin are two medications that may show anticancer effects. The selection criteria for these drugs were based on a comprehensive and established pharmacokinetic and safety profile, along with their proven effectiveness against cancer, as demonstrated by several previous studies.

Several studies have explored the anti-cancer effects of metronidazole. Earlier ones suggest that metronidazole might inhibit the growth of CHO (Chinese hamster ovary) cells, HeLa cells (originating from cervical cancer), and human marrow cells. Nonetheless, this effect appears to be influenced by both the concentration of the drug and the degree of hypoxia [20, 21]. Additionally, metronidazole demonstrated cytotoxic effects on the MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line. Cytotoxicity was noted at higher concentrations, up to 250 µg/ml, following 72 hours of incubation [22].

A recent study has explored the anticancer properties of metronidazole, focusing on its selective cytotoxic effects in low-oxygen settings. Consequently, the tumor microenvironments often show hypoxia, which results in the enzymatic reduction of metronidazole’s nitro group. This process generates reactive intermediates that lead to DNA damage and activate the death of cancer cells. [23]. Preclinical studies show that pairing metronidazole with radiotherapy boosts tumor sensitivity in low-oxygen regions, thus improving treatment outcomes. [24]. Additionally, in vitro studies with colorectal and glioblastoma cell lines demonstrate that metronidazole derivatives exhibit selective antiproliferative effects, highlighting their potential for repurposing [25].

Likewise, the other mixture component, “ciprofloxacin,” has demonstrated anticancer properties highlighted by numerous earlier studies. A recent investigation into the repurposing of this fluoroquinolone antibiotic has revealed its potential as an anticancer agent, underscoring its capacity to affect cellular pathways crucial for tumor growth. Typically prescribed for bacterial infections, the drug’s inhibition of DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV in prokaryotes has sparked interest in its effects on eukaryotic topoisomerases, which are frequently overexpressed in cancer cells to support rapid growth. In vitro research has shown that ciprofloxacin can induce apoptosis and cause cell cycle arrest in various cancer cell lines. Specifically, studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCT-116) indicated that ciprofloxacin (at concentrations of 50–100 μM) activates caspase-3 and downregulates cyclin D1, leading to G1 phase arrest and apoptosis [26-31]. Similarly, in non-small cell lung cancer (cells from A549), ciprofloxacin inhibited metastasis by decreasing epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) through modulation of the TGF-β/Smad3 pathway [32, 33]. Animal models support these findings. A 2023 study utilizing xenograft mice with triple-negative breast cancer (MDA-MB-231 cells) demonstrated that a daily dose of ciprofloxacin (20 mg/kg) lowered tumor growth by 40% through ROS-mediated DNA damage and p53 activation upregulation [34].

The RAS-MAPK signaling pathway governs essential cellular functions such as proliferation, differentiation, survival, and apoptosis. Disruption of this pathway is a hallmark of cancer [35].

The small GTPase family RAS, which includes HRAS, KRAS, and NRAS, is essential for regulating cellular growth, survival, and differentiation through signaling pathways such as MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT [36]. Oncogenic RAS mutations, which occur in approximately 19% of cancers, lead to sustained GTP-bound activation, promoting uncontrolled tumor growth and resistance to treatment. KRAS mutations are particularly prevalent in pancreatic cancer (90%), colorectal cancer (40%), and non-small cell lung cancer (30%) [37]. RAS was considered “undruggable” due to its smooth structure and picomolar affinity for GTP, making direct inhibition difficult. Nevertheless, new developments, including allele-specific covalent inhibitors designed for KRAS G12C (such as Sotorasib and Adagrasib), have shown clinical effectiveness in NSCLC, indicating a significant shift in the approach to treating RAS-driven cancer malignancies [38]. These inhibitors maintain KRAS G12C in a dormant GDP-bound state, inhibiting downstream signalling. Recent research highlights the importance of combining counter-resistance strategies, such as KRAS inhibitors with SOS1, SHP2 inhibitors, or immune checkpoint blockers, to enhance antitumor responses. Moreover, cryo-EM and molecular modelling advances reveal new regions for targeting specific mutants [39, 40].

Moreover, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 (ERK2), which is also known as MAPK1, is a key effector in the MAPK pathway and has a vital role in cancer progression by influencing cell proliferation, survival, and metastasis. As one of the primary ERK isoforms (ERK1 and ERK2), ERK2 frequently shows hyperactivation in tumors caused by upstream RAS/RAF mutations or growth factor receptor signaling [41]. In contrast to ERK1, ERK2 possesses distinctive roles in cancer cell motility and invasion. Studies indicate that it is essential for the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) across different carcinoma types [42]. Continuous ERK2 activation leads to uncontrolled cell cycle progression by phosphorylating targets like RSK and c-Myc and enhancing resistance to targeted therapies [43]. A recent study has highlighted the localization of nuclear versus cytoplasmic ERK2 as a key factor in oncogenic output, with nuclear ERK2 enhancing transcriptional programs that sustain tumor growth [44]. Despite the development of ERK1/2 dual inhibitors (e.g., Ulixertinib), selectively targeting ERK2 remains challenging due to the structural similarities with ERK1. However, novel allosteric inhibitors and proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) are promising strategies to disrupt ERK2-dependent processes and signaling processes.

Due to their crucial roles in cancer, ERK2 and RAS kinase signaling proteins are positioned as promising targets for effective cancer treatment therapies. Several trials have been carried out to identify ERK2 inhibitors, such as Ulixertinib [45], Temuterkib [46] and MK-8353 [47]. Furthermore, various initiatives were undertaken to identify an agent that can target the RAS kinase protein. Such as Sotorasib [48], Adagrasib [49] and GDC-6036 [50].

Marketed drug repositioning for cancer treatment offers a promising approach for creating effective therapies. Numerous studies have explored this idea, including one that showed the amygdalin esomeprazole combination effectively destroys cervical cancer cells, with the effectiveness dependent on the medication’s concentration and the duration of the incubation period. [13, 14]. A recent study showed that the combination of laetrile and vinblastine notably reduced the growth of esophageal cancer, suggesting a synergistic interaction between the two components [19, 51]. Another study shows that the pairing of ciprofloxacin and laetrile significantly hinders the growth of esophageal cancer cells [15]. Another demonstrated the linagliptin-metformin combination’s capacity to inhibit the HeLa cancer cell line’s growth synergistically [17].

Despite numerous studies on this issue, they have not demonstrated the anticancer effects of the metronidazole- ciprofloxacin mixture and its capacity to target RAS and ERK2 kinase signaling proteins. This study investigated the metronidazole-ciprofloxacin mixture’s anticancer properties and molecular mechanisms by assessing its ability to target the MAPK-RAS signaling proteins.

2. Materials and Methods

2-1- Medications

Metronidazole and ciprofloxacin (as raw materials) were sourced from the Samarra Pharmaceutical Factory in Iraq. Serial dilutions of each treatment were prepared using MEM media to achieve concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 1000 µg/ml. For the mixture, the individual concentrations of metronidazole and ciprofloxacin varied between 0.05 and 50 µg/ml, resulting in a combined concentration of 0.1 to 1000 µg/ml./ml.

2-2- Cytotoxicity Assay

Cytotoxicity assessment was performed on HeLa cancer cells to evaluate the anticancer capabilities of metronidazole, ciprofloxacin, cisplatin, and the metronidazole-ciprofloxacin mixture. Additionally, despite the mixture’s established pharmacokinetics and safety profile, the cytotoxicity of the mix was tested on the NHF cell line, which represents a “normal healthy cell line.” This was done to assess the safety of the mixture and to determine whether any drug-pharmaceutical interactions occurred between the components that might negatively impact normal cells.

The cytotoxicity and safety characteristics of metronidazole, ciprofloxacin, cisplatin, and the metronidazole-ciprofloxacin mixture were examined by evaluating the viability of cancerous and healthy normal cells at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 100 µg/ml for each treatment.

2-2-1- Cell Lines Used: The following cell line was used as a model in the study.

HeLa cell line: The cell line originated from cervical cancer cells [52, 53].

NHF cell line: The cell line that originated from Normal human-derived adipose tissue [54].

2-2-2- Cell culture conditions

The cell lines were cultured in MEM media (US Biological, USA), supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Capricorn-Scientific, Germany). To prevent bacterial contamination, the medium contained 100 IU/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Capricorn-Scientific, Germany). Cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C, and all experiments were conducted using cells in the exponential growth phase [55].

2-2-3- MTT cytotoxicity assay

The MTT colorimetric assay measures cell viability through mitochondrial activity. In this method, metabolically active cells reduce the yellow MTT tetrazolium salt to purple formazan crystals via mitochondrial dehydrogenase enzymes. The assay is performed by culturing cells in 96-well plates and treating them with varying concentrations of test compounds. After an appropriate incubation period, MTT reagent is added to each well and incubated for further use. Only viable cells with active metabolism convert MTT into the insoluble purple formazan product. Following the dissolution of these crystals, the absorbance of the resulting solution is quantified spectrophotometrically at a specific wavelength, providing a quantitative measure of cell viability.

The number of viable cells precisely determines the amount of formazan generated. Cytotoxicity is indicated by a reduction in formazan generation after treatment with the test chemical, affecting absorbance. The dose-response curve helps determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) [19].

Cells were seeded in 96-well microplates at a density of 10,000 cells per well and cultured at 37°C for 24 hours to achieve monolayer confluence. The cytotoxicity of compounds was assessed using the MTT assay, evaluating metronidazole, ciprofloxacin, cisplatin, and their mixture over a concentration range of 0.1 to 1000 µg/ml, with six replicates for each concentration. Untreated wells served as negative controls.

Following 24- and 72-hour treatment periods, 28 µL of MTT solution (2 mg/ml) was added to each well and incubated for 3 hours. The formazan crystals were then solubilized with 100 μL DMSO during a 15-minute incubation. Absorbance measurements at 570 nm were obtained using a microplate reader. Cytotoxicity percentages were calculated using the following formula:

Growth inhibition %= (optical density of control wells-optical density of treated wells)/(optical density of control wells)*100%

OD control signifies the mean optical density of untreated wells, whereas OD Sample represents the optical density of treated wells [56].

2-2-3-1- Selective toxicity index

The selective toxicity index score was calculated to evaluate the selective toxicity of the metronidazole- ciprofloxacin mixture and cisplatin against cancer cells over 24- and 72-hour incubation periods. After determining the IC50 levels for the mixture and cisplatin, the selective cytotoxicity index was estimated using a mathematical equation derived from cell growth curves for each HeLa and NHF cell line [57].

Selective toxicity Index (SI)=(IC 50 ofnormal cell lines)/(IC 50 ofcancer cell lines)

An SI score greater than 1.0 indicates that a drug targets cancer cells more effectively than normal cells.

2-2- 3-2- Molecular docking

Using the ChemDraw application (Cambridge Soft, USA), the chemical structures of metronidazole and ciprofloxacin were generated and refined with Chem3D version. Results from a pilot study that performed a screening of the chemical docking of metronidazole and ciprofloxacin with the RAS-MAPK signaling pathway indicated that the best interaction of metronidazole and ciprofloxacin was with human ERK2 and RAS GTPase. The molecular structures of human ERK2 (PDB: 2Y9Q) and human RAS (PDB: 6IY1) were sourced from the Protein Data Bank.

AutoDock Tools optimized and modified protein structures. This program identified the best ligand configurations and generated PDBQT files for them. Once optimization was complete, the structures of the ligands (metronidazole and ciprofloxacin) and the human ERK2 and RAS GTPase were processed in AutoDock Tools. The docking procedure was then performed using the same software. The docking energy scores and binding interactions were analyzed with BIOVIA Discovery Studio, UCSF Chimera, and AutoDock Vina [58, 59].

2-2- 3-3- (Combination Index- CI) Scoring

Compusyn, a computational simulator, was utilized to determine the combination index (CI) and dose reduction index (DRI) scores. The evaluation of the CI score sought to assess the likelihood of synergistic, additive, or antagonistic interactions among the mixture’s components. Concentration-effect curves can demonstrate the percentage of cells displaying reduced growth concerning drug concentration, assessed after 24 and 72 hours of treatment. CI values below 1 suggest synergistic impact, equal to 1 denotes additivity, and values above 1 reflect antagonism. Compusyn software (Biosoft, Ferguson, MO, USA) calculated the combination index values [60, 61].

2-2- 3-4- (dose reduction index- DRI) Scoring

Compusyn, a computational simulator, was used to determine the dose reduction index (DRI) scores. The DRI score estimation quantifies how much the concentration of each drug in a mixture can be reduced while maintaining its cytotoxic effectiveness. A DRI exceeding 1 indicates a favorable concentration reduction, whereas a DRI below 1 indicates an unfavorable concentration reduction. Compusyn software (Biosoft, Ferguson, MO, USA) calculated the dose reduction index values [60, 61].

2-2- 3-5- Ethical approval

This study was conducted solely using in vitro cell line models, without any experimentation involving human participants or laboratory animals. All research procedures complied with institutional ethical guidelines for laboratory-based investigations.

2-2- 3-6- Statistical Analysis

Cytotoxicity results are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). We evaluated intergroup variability using one-way ANOVA and post-hoc pairwise comparisons with LSD tests. For direct group comparisons, we applied paired t-tests. All analyses were conducted in SPSS (version 20), with statistical significance determined as p < 0.05 [62].

To enhance data interpretation, we implemented a letter-coding system in our tables. Where Groups sharing the same letter indicate statistically similar means. Different letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05) between groups. This visual method Simplifies comparison of multiple groups at a glance, reduces the need for repetitive statistical annotations, and maintains rigor while improving readability.

3. Results

3-1- Cytotoxic study

Initially, we evaluated the cytotoxicity of metronidazole and ciprofloxacin separately before assessing the cytotoxic effects of their mixture. This preliminary evaluation aimed to clarify the mechanisms of cytotoxicity and investigate the interactions between the mixture’s components, specifically examining whether these interactions demonstrate synergistic, antagonistic, or additive effects.

3-1-1- Metronidazole Cytotoxicity

The study results on metronidazole’s efficacy in inhibiting HeLa cell proliferation depended on the concentration of metronidazole and the duration of incubation. A reduction in the IC50 time interval effect (Table 1).

| Concentration (µg/ml) | Inhibition of cellular proliferation (mean ± SD) | P- value | |

| 24 hr. | 72 hr. | ||

| 0.1 | B 0.00 ± 0.000 | C 3.00 ± 2.000 | 0.026 * |

| 1 | B 1.00 ± 1.000 | BC 10.00 ± 5.000 | 0.038 * |

| 10 | A 6.00 ± 3.000 | B 18.00 ± 5.000 | 0.023 * |

| 100 | A 11.00 ± 1.000 | B 22.00 ± 2.000 | 0.001 * |

| 1000 | AB 16.00 ± 6.000 | A 37.00 ± 2.000 | 0.005 * |

| LSD value | 11.16 | 12.82 | - |

| IC 50 | 3651 µg/ml | 1489 µg/ml | - |

*, significant at (P<0.05)

3-1-2- Ciprofloxacin cytotoxicity

Ciprofloxacin exhibited cytotoxic effects on cervical cancer cells, inhibiting cellular proliferation, which intensified with higher concentrations of ciprofloxacin and more extended incubation periods. The latter factor has a more pronounced effect on growth inhibition than concentration. The decline in the IC50 level between each incubation period indicated a time-dependent manner of growth inhibition (Table 2).

| Concentration (µg/ml) | Inhibition of cellular proliferation (mean ± SD) | P- value | |

| 24 hr. | 72 hr. | ||

| 0.1 | C 0.00 ± 0.000 | C 4.00 ± 2.000 | 0.026 * |

| 1 | C 0.00 ± 0.000 | C 11.00 ± 3.000 | 0.004 * |

| 10 | C 3.00 ± 2.000 | B 32.00 ± 2.000 | 0.000 * |

| 100 | B 19.00 ± 4.000 | A 43.00 ± 3.000 | 0.001 * |

| 1000 | A 29.00 ± 2.000 | A 47.00 ± 1.000 | 0.0001 * |

| LSD value | 7.98 | 8.46 | |

| IC 50 | 1771 µg/ml | 1035 µg/ml |

*, significant at (P<0.05)

3-1-3- Cisplatin cytotoxicity

For comparative purposes, cisplatin was selected as a positive control. Its cytotoxicity revealed its ability to inhibit the growth of each cell line (HeLa and NHF) in a concentration and time-dependent manner. IC50 level dropping at 72 hours compared to 24 hours of incubation, supporting a time-dependent manner of inhibition (Table 3).

| Inhibition of cellular proliferation (mean ± SD) | ||||||

| Concentration (µg/ml) | HeLa cell line | NHF cell line | ||||

| 24 hr. | 72 hr. | P- value | 24 hr. | 72 hr. | P- value | |

| 0.1 | C 0.00 ± 0.000 | C 5.00 ± 2.000 | 0.012 * | D 2.00 ± 1.000 | E 11.00 ± 1.000 | 0.0001 * |

| 1 | B 2.00 ± 2.000 | BC 11.00 ± 1.000 | 0.002 * | CD 10.00 ± 5.000 | D 22.00 ± 2.000 | 0.018 * |

| 10 | BC 10.00 ± 2.000 | B 18.00 ± 3.000 | 0.018 * | C 17.00 ± 4.000 | C 35.00 ± 2.000 | 0.002 * |

| 100 | A 33.00 ± 3.000 | A 43.00 ± 3.000 | 0.015 * | B 34.00 ± 4.000 | B 49.00 ± 5.000 | 0.015 * |

| 1000 | A 41.00 ± 1.000 | A 56.00 ± 6.000 | 0.013 * | A 51.00 ± 1.000 | A 66.00 ± 2.000 | 0.0001 * |

| LSD value | 6.9 | 12.5 | - | 12.3 | 10.04 | - |

| IC 50 | 1213 µg/ml | 800 µg/ml | - | 933 µg/ml | 556 µg/ml | - |

*, significant at (P<0.05)

3-1-4-(metronidazole-ciprofloxacin) mixture cytotoxicity

The study outcomes indicated that the metronidazole- ciprofloxacin mixture suppressed the growth of human cervical cancer, with the inhibitory mechanism influenced by both the mixture’s concentration and the duration of treatment. Moreover, the cytotoxicity of the mixture on the NHF cell line was less pronounced than that on the cancer cell line, suggesting a favorable safety profile and selective toxicity toward cancer cells (Table 4, 5).

| Inhibition of cellular proliferation (mean ± SD) | ||||||

| Concentration (µg/ml) | HeLa cell line | NHF cell line | ||||

| 24 hr. | 72 hr. | P- value | 24 hr. | 72 hr. | P- value | |

| 0.1 | D 5.00 ± 3.000 | C 13.00 ± 3.000 | 0.031 * | B 0.00 ± 0.000 | B 0.00 ± 0.000 | N. S |

| 1 | CD 11.00 ± 1.000 | C 20.00 ± 5.000 | 0.038 * | B 0.00 ± 0.000 | B 0.00 ± 0.000 | N. S |

| 10 | C 24.00 ± 4.000 | B 36.00 ± 3.000 | 0.014 * | AB 1.00 ± 1.000 | AB 2.00 ± 2.000 | 0.482 |

| 100 | B 39.00 ± 1.000 | B 47.00 ± 5.000 | 0.053 | A 7.00 ± 2.000 | A 10.00 ± 1.000 | 0.081 |

| 1000 | A 56.00 ± 1.000 | A 71.00 ± 1.000 | 0.0001 * | A 11.00 ± 3.000 | A 15.00 ± 5.000 | 0.3 |

| LSD value | 8.62 | 13.52 | - | 6.08 | 8.92 | - |

| IC 50 | 805 µg/ml | 501 µg/ml | - | 4937 µg/ml | 3627 µg/ml | - |

*, significant at (P<0.05)

| Concentration (µg/ml) | Inhibition of cellular proliferation (mean ± SD) | |||||

| 24 hr. | 72 hr. | |||||

| HeLa cell line | NHF cell line | P- value | HeLa cell line | NHF cell line | P- value | |

| 0.1 | D 5.00 ± 3.000 | B 0.00 ± 0.000 | 0.045 * | C 13.00 ± 3.000 | B 0.00 ± 0.000 | 0.002 * |

| 1 | CD 11.00 ± 1.000 | B 0.00 ± 0.000 | 0.0001 * | C 20.00 ± 5.000 | B 0.00 ± 0.000 | 0.002 * |

| 10 | C 24.00 ± 4.000 | AB 1.00 ± 1.000 | 0.001 * | B 36.00 ± 3.000 | AB 2.00 ± 2.000 | 0.0001 * |

| 100 | B 39.00 ± 1.000 | A 7.00 ± 2.000 | 0.0001 * | B 47.00 ± 5.000 | A 10.00 ± 1.000 | 0.0001 * |

| 1000 | A 56.00 ± 1.000 | A 11.00 ± 3.000 | 0.0001 * | A 71.00 ± 1.000 | A 15.00 ± 5.000 | 0.0001 * |

| LSD value | 8.62 | 6.08 | - | 13.52 | 8.92 | - |

| IC 50 | 805 µg/ml | 4937 µg/ml | - | 501 µg/ml | 3627 µg/ml | - |

*, significant at (P<0.05)

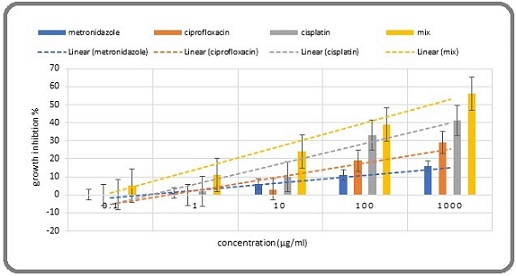

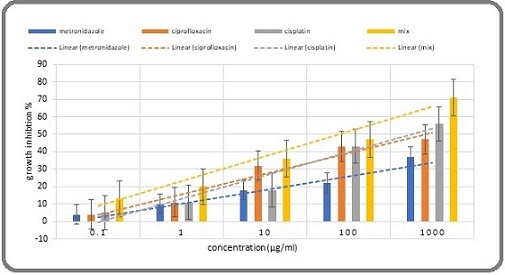

During each incubation period, particularly during the 24-hour incubation, the growth inhibition of the mixture was significantly greater than that of cisplatin and its components (Table 6, 7, 10 and Figure 1, 2).

| Concentration (µg/ml) | Growth inhibition (mean ± SD) | LSD value | |||

| Cisplatin | Metronidazole | Ciprofloxacin | Mix | ||

| 0.1 | C 0.00 ± 0.000 a | B 0.00 ± 0.000 a | C 0.00 ± 0.000 a | D 5.00 ± 3.000 a | N. S |

| 1 | B 2.00 ± 2.000 b | B 1.00 ± 1.000 b | C 0.00 ± 0.000 b | CD 11.00 ± 1.000 a | 4.62 |

| 10 | BC 10.00 ± 2.000 b | A 6.00 ± 3.000 b | C 3.00 ± 2.000 b | C 24.00 ± 4.000 a | 10.82 |

| 100 | A 33.00 ± 3.000 a | A 11.00 ± 1.000 b | B 19.00 ± 4.000 b | B 39.00 ± 1.000 a | 9.78 |

| 1000 | A 41.00 ± 1.000 b | AB 16.00 ± 6.000 c | A 29.00 ± 2.000 b | A 56.00 ± 1.000 a | 12.2 |

| LSD value | 6.9 | 11.16 | 7.98 | 8.62 | - |

| IC 50 | 1213 µg/ml | 3651 µg/ml | 1771 µg/ml | 805 µg/ml | - |

significant at (P<0.05)

| Concentration (µg/ml) | Growth inhibition (mean ± SD) | LSD value | |||

| Cisplatin | Metronidazole | Ciprofloxacin | Mix | ||

| 0.1 | C 0.00 ± 0.000 a | B 0.00 ± 0.000 a | C 0.00 ± 0.000 a | D 5.00 ± 3.000 a | N. S |

| 1 | B 2.00 ± 2.000 b | B 1.00 ± 1.000 b | C 0.00 ± 0.000 b | CD 11.00 ± 1.000 a | 4.62 |

| 10 | BC 10.00 ± 2.000 b | A 6.00 ± 3.000 b | C 3.00 ± 2.000 b | C 24.00 ± 4.000 a | 10.82 |

| 100 | A 33.00 ± 3.000 a | A 11.00 ± 1.000 b | B 19.00 ± 4.000 b | B 39.00 ± 1.000 a | 9.78 |

| 1000 | A 41.00 ± 1.000 b | AB 16.00 ± 6.000 c | A 29.00 ± 2.000 b | A 56.00 ± 1.000 a | 12.2 |

| LSD value | 6.9 | 11.16 | 7.98 | 8.62 | - |

| IC 50 | 1213 µg/ml | 3651 µg/ml | 1771 µg/ml | 805 µg/ml | - |

significant at (P<0.05)

Figure 1. A Comparison of 24-hour Growth Inhibition among Metronidazole, Ciprofloxacin, a Mixture, and Chemotherapy.

Figure 2. A Comparison of 72-hour Growth Inhibition among Metronidazole, Ciprofloxacin, a Mixture, and Chemotherapy.

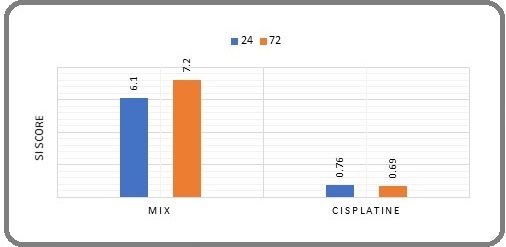

3-2- Selective toxicity index study

The SI score for the mixture was 6.1 at 24 hours and 7.2 at 72 hours, indicating favorable selective toxicity toward cancer cells compared to normal healthy cells. The cisplatin SI score was 0.76 at 24 hours and 0.69 at 72 hours, respectively, indicating lower selective toxicity toward cancer cells than healthy cells (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Comparison of the Mixture with Cisplatin SI over 24 and 72 hours. (An SI greater than 1.0 indicates that a drug is more effective against tumor cells compared to its toxicity towards normal cells).

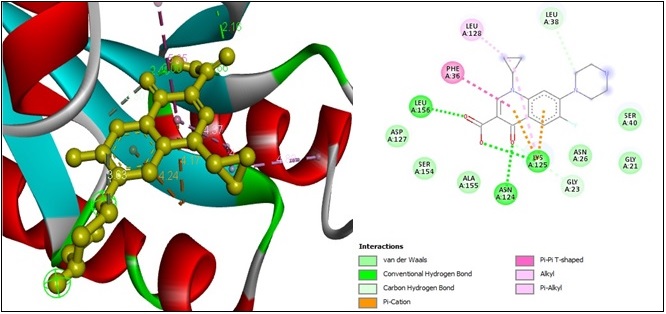

3-3- Molecular docking studies

A computational molecular docking simulation examined the binding affinity of the drug mixture (metronidazole and ciprofloxacin) with various signal protein kinases in the Ras-MAPK pathway. The results indicated that ciprofloxacin had a higher affinity for binding with RAS GTPase (PDB code: 6iy1), yielding a docking score equal to (-7.3) kcal/mol. At the same time, metronidazole exhibited a greater affinity for ERK2 kinase proteins (PDB code: 2y9q), with a docking score equivalent to (-6.3) kcal/mol.

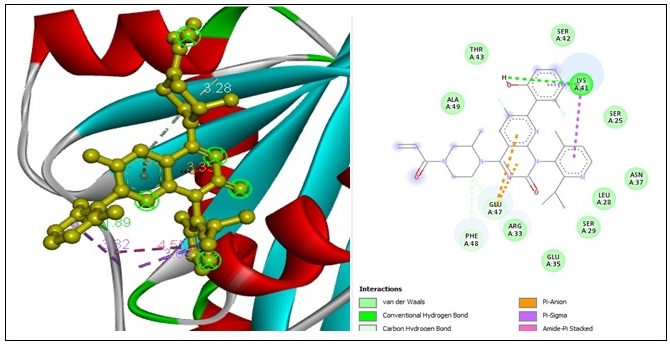

The exploration of molecular docking interactions between ciprofloxacin and RAS GTPase yielded the following outcomes. Four “conventional hydrogen bonds” with the ASN A:124, LYS A:125, LEU A:156, and UNK A:42 amino acid residues at 2.48 Å, 2.65 Å, 2.15 Å, and 2 Å of distance formed subsequently. Two “carbon-hydrogen bond” constrictions occur with GLY A:23 and LEU A:38 amino acid residues at 3.29 Å and 3.6 Å of distance. Two “pi-cation bonds” formed with the two LYA A:125 amino acid residues at a 4.17 Å and 4.24 Å distance, respectively, and one “pi-pi T-shaped bond” with PHE A:36 amino acid residues at 5.34 Å of distance. Two “alkyl bonds” with LYS A:125 and LEU A:128 amino acid residues at a 4.78 Å and 4.88 Å distance, respectively. Finally, one “Pi-alkyl bond” constrains with LYS A:125 amino acid residues at 4.37 Å of distance (Figure 4).

Figure 4. 2D and 3D Structures for the Binding Site of Ciprofloxacin with Human RAS GTPase.

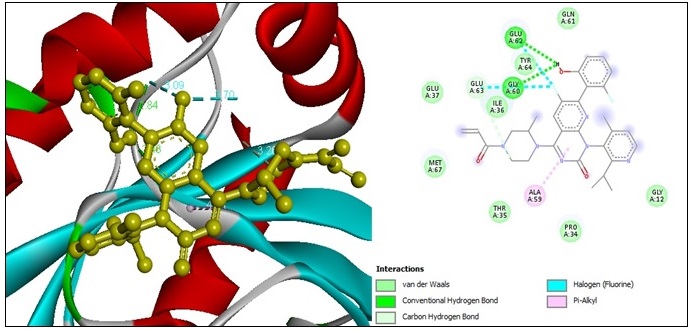

A molecular docking study was conducted for comparative purposes to assess the interaction between Sotorasib, a “RAS GTPase inhibitor” [63, 64]. And RAS GTPase, revealing a docking score of -7.6 kcal/mol for binding and presenting. One “conventional hydrogen bond” constrains the LYS A:41 amino acid residues at a distance of 1.88 Å. Two “carbon-hydrogen bonds” constrict with GLU A:47 and PHE A:48 amino acid residues at a distance of 3.48 Å and 3.27 Å, distance. Two “pi-pi anion bond” constrictions are formed with two GLU A:47 amino acid residues at 3.35 Å and 3.51 Å of distance. Two “pi-pi sigma bond” constrains with two LYS A:41 amino acid residues at 3.68 Å and 3.81 Å of distance subsequently. Finally, one “amine pi-stacked bond” constrains with LYS A:194 amino acid residues at 4.54 Å of distance (Figure 5).

Figure 5. 2D and 3D Structures for the Binding Site of Sotorasib with Human RAS GTPase.

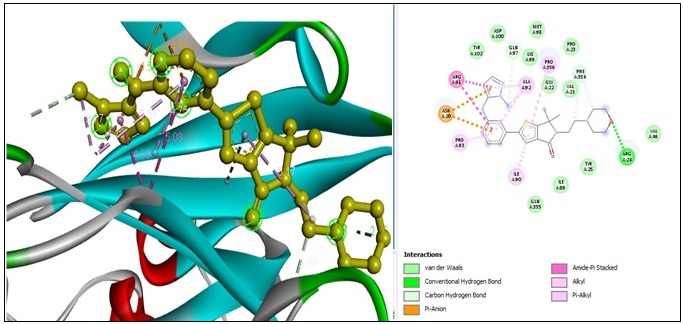

Moreover, The analysis of molecular docking for the interaction of “metronidazole” with the ERK2 protein kinase revealed the following bonds: seven “conventional hydrogen bonds” involving four ARG A:148 and three ARG A:172 amino acid residues at distances of 2.96 Å, 2.01 Å, 2.34 Å, 2.05 Å, 2.06 Å, 2.68 Å, and 2.40 Å.

Additionally, there were two “carbon-hydrogen bonds” involving GLN A:66 and GLU A:169 amino acid residues at distances of 3.48 Å and 3.66 Å, respectively. There were also two “alkyl bonds” involving ARG A:67 and LEU A:170 amino acid residues at distances of 4.22 Å and 5.18 Å. Finally, one “alkyl bond” involved the LEU A:170 amino acid residue at a distance of 5.36 Å (Figure 6).

Figure 6. 2D and 3D Structures for the Binding Site of Metronidazole with Human ERK2.

Temuterkib was chosen as an “ERK2 inhibitor.” [64] To compare its docking with the ERK2 kinase protein against metronidazole. The molecular docking results from the interaction between Temuterkib and the ERK2 kinase protein yield a docking score of (-8.4) kcal/mol. One “conventional hydrogen bond” constricted with ARG A:24 amino acid residues at a distance of 2.45 Å. Three “carbon-hydrogen bond” constrictions are observed with GLN A:97, PHE A:354, and PHE A:354 at 3.37 Å, 3.43 Å, and 3.74 Å of distance. Two “pi-anion bonds” constrict with two ASP A:20 amino acid residues at 4.48 Å, 4.58 Å of distance subsequently. Two “amide-pi-stacked bonds” constrict with two ARG A:91 amino acid residues at 5.08 Å, 4.09 Å of distance; subsequently, one “alkyl bonds” constrict with ALA A:91 amino acid residues at 3.76 Å of distance. And finally, five “pi-alkyl bond” constrictions are formed with ILE A:90, PRO A:356, ALA A:92, PRO A:93, and ALA A:92 amino acid residues at 2.62 Å, 5.17 Å, 5.21 Å, 4.74 Å, and 4.18 Å of distance (Figure 7).

Figure 7. 2D and 3D Structures for the Binding Site of Temuterkib with Human ERK2.

To clarify the effectiveness of the mixture’s ability to target the kinase signaling proteins (RAS and ERK2), their docking scores and conventional hydrogen bonds were compared with those of standard medicine (Table 8).

| Cellular target | (docking scores) kcal/mol | Number of conventional hydrogen bonds | ||||||

| metronidazole | Temuterkib | ciprofloxacin | Sotorasib | metronidazole | Temuterkib | ciprofloxacin | Sotorasib | |

| RAS GTPase | - | - | -7.3 | -7.6 | - | - | 4 | 1 |

| ERK2 kinase protein | -6.3 | -8.4 | - | - | 7 | 1 | - | - |

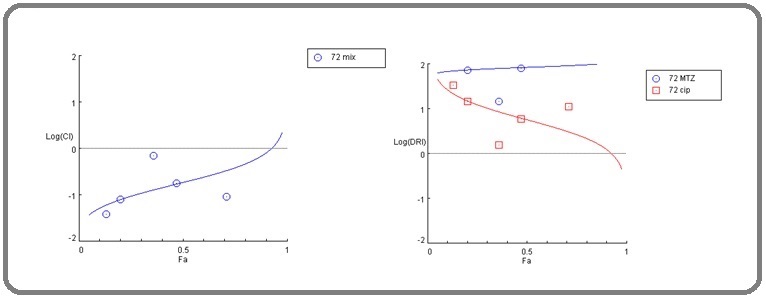

3-4- (Combination Index- CI) Scoring

The CI score indicated a diverse pattern of combinations among the mixture ingredients. After 24 hours of incubation, concentrations of 0.1, 1, and 10 μg/ml exhibited very strong synergism, while 100 μg/ ml displayed strong synergism. Furthermore, 10 μg/ml revealed a nearly additive effect pattern.

After 72 hours of incubation, 0.1 and 1 μg/ml concentrations exhibited very strong synergism, while 10 μg/ml showed moderate synergism. Furthermore, a concentration of 100 μg/ml demonstrated strong synergism. Lastly, 1000 μg/ml displayed very strong synergistic effects (Table 9,10 and Figure 8, 9)

| Concentration μg/ml | CI score | Combination pattern | DRI score | ||||

| Metronidazole | Ciprofloxacin | Mix | Ratio | metronidazole | ciprofloxacin | ||

| 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 1:01 | 0.0016 | Very Strong Synergism | 1025.82 * | 1598.28 * |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.00736 | Very Strong Synergism | 248.532 * | 299.514 * | |

| 5 | 5 | 10 | 0.03196 | Very Strong Synergism | 65.7159 * | 59.7224 * | |

| 50 | 50 | 100 | 0.1729 | Strong Synergism | 13.6523 * | 10.0348 * | |

| 500 | 500 | 1000 | 0.95931 | Nearly Additive | 2.78701 * | 1.66526 * |

| Concentration μg/ml | CI score | Combination pattern | DRI score | ||||

| Metronidazole | Ciprofloxacin | Mix | ratio | metronidazole | ciprofloxacin | ||

| 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 1:01 | 0.03909 | Very Strong Synergism | 109.400 * | 33.3930 * |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.08074 | Very Strong Synergism | 73.4551 * | 14.8970 * | |

| 5 | 5 | 10 | 0.70397 | Moderate Synergism | 14.7602 * | 1.57178 * | |

| 50 | 50 | 100 | 0.18208 | Strong Synergism | 79.5381 * | 5.89960 * | |

| 500 | 500 | 1000 | 0.09159 | Very Strong Synergism | 340.729 * | 11.2796 * |

The CI (Combination Index) and DRI (Dose Reduction Index) Values were estimated by using Compusyn software. (A CI >1 indicates antagonism, a CI = 1 denotes an additive effect, and a CI ˂1 suggests synergism. A (DRI) >1 correlates with reduced toxicity. * denotes a positive reduction in the effective cytotoxic concentration [65].

Figure 8. Log CI (left) and Log DRI (right) for the Mixture after a 24-hour Incubation Period. MTZ: metronidazole, CIP: ciprofloxacin, CI: combination index, DRI: dose reduction index.

Figure 9. Log CI (left) and Log DRI (right) for the Mixture after a 72-hour Incubation Period. MTZ: metronidazole, CIP: ciprofloxacin, CI: combination index, DRI: dose reduction index.

3-5- (dose reduction index- DRI) Scoring

Throughout each incubation period, the dose reduction index score indicated that the concentrations of each ingredient in the mixture, which produced a significant cytotoxicity, were lower than their corresponding significant cytotoxic concentrations when used individually. The observed decline in concentrations suggests a reduced likelihood of side effects from the mixture compared to the probability of side effects connected with each drug individually (Table 9, 10 and Figure 8, 9).

3-6- Morphological Assessment of Cytotoxicity

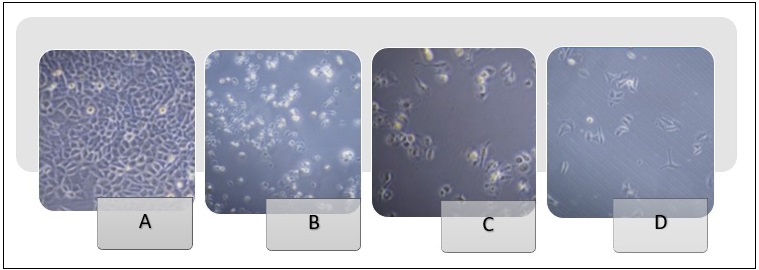

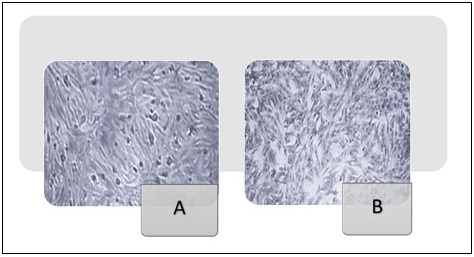

Microscopic examination of HeLa and NHF cells after 72 hours of treatment revealed notable morphological changes, as demonstrated in Figures 10 and 11.

Figure 10. Morphological Characteristics of the HeLa cell line (400x). (A) (Hela cell cancer line), untreated. (B) Hela cells were treated with 100 µg/ml metronidazole for 72 hours. (C) Hela cells exposed to 1000 µg/ml of ciprofloxacin for 72 hours. (D) Hela cells were exposed to a metronidazole-ciprofloxacin mixture at a 1000 µg/ml concentration for 72 hours.

Figure 11. Morphological Characteristics of the NHF Cell Line (400x). (A) (NHF cell line) untreated. (B) NHF normal cells underwent exposure to a mixture of metronidazole and ciprofloxacin at a concentration of 1000 µg/ml for 72 hours.

4. Discussion

Reassessing existing non-cancer medications offers an opportunity to provide alternative treatments. Accordingly, this study investigates the anticancer effects of combining ciprofloxacin and metronidazole. This choice of drugs stems from various earlier studies indicating their anticancer potential. Furthermore, both drugs were rigorously evaluated for their pharmacokinetics and safety profile.

The MTT assay results showed that the metronidazole- ciprofloxacin combination inhibited cervical cancer growth and exhibited reduced cytotoxicity towards normal healthy cell lines. The mixture showed improved anticancer effectiveness compared to the cytotoxicity of cisplatin and each component of the mix. The CI score suggests that the two medications work together synergistically. Furthermore, regarding safety, the DRI score indicated that this mixture presents a reduced risk of adverse effects compared to its components. The safety of the mix is supported by its favorable selectivity index score, indicating selective toxicity towards cancer cells compared to healthy cells.

The anticancer mechanism of the mixture can be understood through two approaches: first, by analyzing the suggested anticancer mechanisms of each component from various previous studies, and second, by considering the novel anticancer mechanism introduced through our molecular docking study.

A variety of studies have explored the anticancer effects of metronidazole. Earlier research suggests that metronidazole might help decrease the growth of CHO (Chinese hamster ovary), HeLa cells (from cervical cancer), and human marrow cells. Nonetheless, this effect appears to be influenced by both the concentration of the drug and the degree of hypoxic conditions [20, 21], and showed cytotoxic effects on the MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line. Cytotoxicity was noted at elevated concentrations, up to 250 µg/ml, after 72 hours of incubation [22].

Recent studies have examined the anticancer potential of metronidazole, particularly its selective cytotoxic effects in low-oxygen environments. Tumor microenvironments frequently exhibit hypoxia, leading to the enzymatic reduction of the nitro group in metronidazole, which produces reactive intermediates that harm DNA and initiate cancer cell death [23]. Preclinical studies show that combining metronidazole with radiotherapy enhances tumor sensitivity in hypoxic regions, improving therapeutic outcomes [24]. Furthermore, in vitro studies involving colorectal and glioblastoma cell lines demonstrate that metronidazole derivatives exhibit selective antiproliferative effects, highlighting their potential for repurposing [25].

Several studies have examined the anticancer effects of ciprofloxacin. A recent survey regarding the repurposing of this fluoroquinolone antibiotic has uncovered its potential as an anticancer agent, emphasizing its ability to influence cellular pathways essential for tumor growth. Traditionally prescribed for bacterial infections, the drug’s inhibition of DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV in prokaryotes has raised interest in its impact on eukaryotic topoisomerases, which are often overexpressed in cancer cells to facilitate rapid growth. In vitro studies have shown that ciprofloxacin can induce apoptosis and cause cell cycle arrest in various cancer cell lines. Specifically, studies on colorectal cancer cells (HCT-116) indicated that ciprofloxacin (at concentrations of 50–100 μM) activates caspase-3 and downregulates cyclin D1, resulting in G1 phase arrest and apoptosis [26-28, 66]. Similarly, in non-small cell lung cancer (A549 cells), ciprofloxacin inhibited metastasis by reducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) via modulation of the TGF-β/Smad3 pathway [32, 33, 67].

Animal models reinforce these results. A study from 2023, which used xenograft mice with triple-negative breast cancer (MDA-MB-231 cells), revealed that a daily dosage of ciprofloxacin (20 mg/kg) reduced tumor growth by 40% via ROS-mediated DNA damage and p53 activation upregulation [34].

Furthermore, in addition to the anticancer mechanisms elucidated earlier, the current study examines novel anticancer mechanisms for each metronidazole and ciprofloxacin, as demonstrated by the findings of the molecular docking study, which suggests their affinity to target ERK2 and RAS GTPase.

The RAS-MAPK pathway regulates cellular functions such as proliferation, differentiation, survival, and apoptosis. An imbalance in this pathway is a defining characteristic of cancer [35].

The RAS family of small GTPases, which includes HRAS, KRAS, and NRAS, is essential for controlling cellular growth, survival, and differentiation via signaling pathways like MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT [36]. Oncogenic RAS mutations, found in roughly 19% of cancers, result in persistent GTP-bound activation, driving uncontrolled tumor growth and resistance to treatment therapy. KRAS mutations are widespread, particularly in pancreatic cancer (90%), colorectal cancer (40%), and non-small cell lung cancer (30%) [37]. Generally, RAS was considered “undruggable” due to its smooth surface and picomolar affinity for GTP, which limited direct inhibition. However, recent breakthroughs, including allele-specific covalent inhibitors that target KRAS G12C (such as Sotorasib and Adagrasib), have shown clinical efficacy in NSCLC, indicating a paradigm shift in targeting RAS-driven malignancies [38]. These inhibitors keep KRAS G12C in a dormant GDP-bound Form, hindering downstream signaling. Recent research emphasizes combining counter-resistance approaches, such as KRAS inhibitors alongside SOS1, SHP2 inhibitors, or immune checkpoint blockers, to boost antitumor responses. Furthermore, cryo-EM and molecular modeling improvements uncover new regions for targeting specific mutants [14, 39, 40].

Additionally, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 (ERK2), another critical effector kinase protein in the MAPK pathway, significantly contributes to cancer progression by modulating cell proliferation, survival, and metastasis. Being one of the two primary ERK isoforms (ERK1 and ERK2), ERK2 is frequently hyperactivated in tumors due to upstream RAS/RAF mutations or growth factor receptor signaling [41]. Unlike ERK1, ERK2 appears to have distinct functions in cancer cell motility and invasion. Studies have demonstrated its necessity for epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in multiple carcinoma types [42]. Persistent ERK2 activation drives uncontrolled cell cycle progression by phosphorylating substrates such as RSK and c-Myc, while also promoting resistance to targeted therapies [43]. A recent study has highlighted nuclear versus cytoplasmic ERK2 localization as a determinant of oncogenic output, with nuclear ERK2 enhancing transcriptional programs that sustain tumor growth [44]. Despite the development of ERK1/2 dual inhibitors (e.g., Ulixertinib), selective targeting of ERK2 remains challenging due to structural similarities with ERK1. However, novel allosteric inhibitors and proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) are emerging as promising strategies to disrupt ERK2-dependent signaling [68].

Given the crucial role of the previously mentioned signal proteins, this study aims to examine the marketing of drugs that target these cellular entities. The findings of our molecular docking study revealed that both metronidazole and ciprofloxacin target specific signal proteins in the RAS-MAPK pathway. This diversity in targeting suggests that using these medications together can potentially have a synergistic effect. The combination index study supports the mixture’s synergistic behavior, which indicates that the combination of drugs acts synergistically when used together. Furthermore, targeting diverse tyrosine kinase proteins within the RAS-MAPK pathway provides a therapy that reduces the development of resistance in cancer cells, thereby enhancing its effectiveness.

The crucial role of ERK2 and RAS GTPase in cancer positions them as promising targets for effective cancer treatment therapies. Several trials have been conducted to identify ERK2 inhibitors, such as Ulixertinib [45], Temuterkib [46], MK-8353 [47]. Furthermore, various initiatives were undertaken to identify an agent that can target the RAS GTPase. Such as Sotorasib [48], Adagrasib [49] and GDC-6036 [50].

Although there are several cancer-targeted therapies, they have notable disadvantages that need to be considered, such as toxicity and side effects, the emergence of resistance, limited efficacy in certain cancers, a narrow spectrum of activity, and high costs [36, 37, 69, 70]. The present study aims to address these gaps.

The research faces limitations, including laboratory validation linked to molecular studies, which are influenced by financial constraints and obstacles.

In conclusion, this study focused on identifying a safe and effective anticancer treatment for cervical cancer through the repurposing of a combination of metronidazole and ciprofloxacin. Results from the MTT assay showed that the combination of metronidazole and ciprofloxacin inhibits the proliferation of cervical cancer cells, significantly more than the growth inhibition caused by chemotherapy (cisplatin), metronidazole, and ciprofloxacin. Metronidazole and ciprofloxacin synergistically enhance their effects, as the CI score indicates.

From a safety standpoint, the drug concentrations in the mixture that induce cytotoxicity are lower than those used individually, indicating that the mixture is relatively safe regarding the occurrence of its side effects.

The mixture shows selectivity, indicating its specific targeting of cancer cells instead of healthy cells. Furthermore, the study explores a novel anticancer mechanism of the mix by focusing on two essential kinase signaling proteins within the MAPK-RAS pathway. This is achieved by targeting the RAS GTPase with ciprofloxacin and the ERK2 kinase protein with metronidazole. This dual targeting of the MAPK-RAS pathway supports the synergistic anticancer effect of the mixture, as demonstrated by the combination index assessment.

In light of these findings, the metronidazole- ciprofloxacin combination offers an attractive alternative therapeutic option for cervical cancer, particularly considering its established pharmacokinetic properties and safety profile.

Acknowledgements

The research team thanks the researchers and instructional staff at ICMGR/Mustansiriyah University in Baghdad and the Iraqi National Cancer Research Center/ University of Baghdad for their essential support during this study. I also wish to express my deep appreciation to the quality control team at the Samarra Pharmaceutical Factory for supplying the drugs used in this research.

Conflicts of interest

The authors indicate that they have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted

technologies in the writing process:

The authors specify that this work does not utilize generative AI or AI-assisted technologies.

Abbreviations

(ICCMGR), The Iraqi Centre for Cancer and Medical Genetics Research; MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)- 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide stain; MEM, Minimum Essential Medium; SAS, Statistical Analysis System; LSD, Least Significant Difference; DRI, dose reduction index; CI, combination index; Hsp 60, heat shock protein 60; NHF cell line, human-derived adipose tissue cell line; PPIs, proton pump inhibitors; HSB, heat shock protein; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; OD, optical density.

Originality Declaration for Figures

All figures included in this manuscript are original and have been created by the authors specifically for the purposes of this study. No previously published or copyrighted images have been used. The authors confirm that all graphical elements, illustrations, and visual materials were generated from the data obtained in the course of this research or designed uniquely for this manuscript.

References

- Incidence and risk factors of VTE in patients with cervical cancer using the Korean national health insurance data Yuk JS , Lee B, Kim MH , Kim K, Seo YS , Hwang SO , Cho YK , Kim YB . Scientific Reports.2021;11(1). CrossRef

- Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: a worldwide analysis Arbyn M, Weiderpass E, Bruni L, Sanjosé S, Saraiya M, Ferlay J, Bray F. The Lancet. Global Health.2020;8(2). CrossRef

- The Effect of Twist Expression On The Development Ofcervical Carcinoma in A Group Of Iraqi Women Infected with Hpv Khashman BM , Abdulla KN , Karim S, Alhashimi S, Mohammed ML , Sarah NA . Biochem Cell Arch.2019;19(2):3913-6.

-

The diagnostic validity of P16

INK4A for cervical carcinoma in a group of Iraqi women infected with HPV Khashman BM . Biochemical and cellular archives.2019. - Cervical cancer screening programmes and age-specific coverage estimates for 202 countries and territories worldwide: a review and synthetic analysis Bruni L, Serrano B, Roura E, Alemany L, Cowan M, Herrero R, Poljak M, et al . The Lancet. Global Health.2022;10(8). CrossRef

- Evaluation of Quality of Life for Women With Breast Cancer Khalifa MF , Ghuraibawi ZAGA , Hade IM , Mahdi MA . Scripta Medica.2024;55(1). CrossRef

- Cervical cancer Cohen PA , Jhingran A, Oaknin A, Denny L. Lancet (London, England).2019;393(10167). CrossRef

- Integrated genomic and molecular characterization of cervical cancer Network CGAR . Nature.2017;543(7645). CrossRef

- Physiological Scrutiny to Appraise a Flavonol Versus Statins Hashim WS , Yasin YS , Jumaa AH , Al-Zuhairi MI , Abdulkareem AH . Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal.2023;16(1).

- Involvement of Total Antioxidant Activity and eNOS Gene rs1799983/ rs2070744 Polymorphisms in Breast Carcinogenesis Hade IM Istikrar M., Al-Khafaji ASK , Lafta FM . Iraqi Journal of Science.2024. CrossRef

- Novel Therapeutics for Recurrent Cervical Cancer: Moving Towards Personalized Therapy Cohen AC , Roane BM , Leath CA . Drugs.2020;80(3). CrossRef

- Changing paradigms in the systemic treatment of advanced cervical cancer Pfaendler KS , Tewari KS . American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology.2016;214(1). CrossRef

- Esomeprazole and amygdalin combination cytotoxic effect on human cervical cancer cell line (Hela cancer cell line) Jumaa AH , Al Uboody WSH , Hady AM . Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research.2018;10(9):2236-41.

- The Effect of Esomeprazole on Cell Line Human Cervical Cancer Jumaa AH , Jarad AS , Al Uboody WSH . ResearchGate.2025.

- The Cytotoxic Effect of Ciprofloxacin Laetrile Combination on Esophageal Cancer Cell Line Jumaa AH , Abdulkareem AH , Yasin YS . Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP.2024;25(4). CrossRef

- Antiproliferative Impact of Linagliptin on the Cervical Cancer Cell Line Muafaq Said A, Abdulla KN , Ahmed NH , Yasin YS . Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP.2024;25(9). CrossRef

- Synergistic Antiproliferative Effect of Linagliptin-Metformin Combination on the Growth of Hela Cancer Cell Line Ahmed A, Sabreen G, Youssef Y, Azal J. Journal of Cancer Research Updates.2025;14:12-23.

- The Cytotoxic Effect Of Ephedra Transitoria On Hela Cancer Cell Line: Bio-Engineering Arean AG , Jumaa AH , Hashim WS , Mohamed AA , Yasin YS . .

- The Cytotoxic Effect Of Ethanolic Extract Of Cnicus Benedictus L. Flowers On The Murine Mammary Adenocarcinoma Cancer Cell Line Amn-3 Yasin Al-Samarray YS , Jumaa AH , Hashim WS , Khudhair YI . Biochemical & Cellular Archives. 2020;20.2020;:20.

- Increased cell killing by metronidazole and nitrofurazone of hypoxic compared to aerobic mammalian cells Mohindra JK , Rauth AM . Cancer Research.1976;36(3).

- MRI Guided Analysis of Changes in Tumor Oxygenation in Response to Hypoxia Activated/Targeted Therapeutics: Arizona State University Agarwal S. 2017.

- Multifunctional Silver(I) Complexes with Metronidazole Drug Reveal Antimicrobial Properties and Antitumor Activity against Human Hepatoma and Colorectal Adenocarcinoma Cells Żyro D, Radko L, Śliwińska A, Chęcińska L, Kusz J, Korona-Głowniak I, Przekora A, et al . Cancers.2022;14(4). CrossRef

- Clinical and Preclinical Outcomes of Combining Targeted Therapy With Radiotherapy Elbanna M, Chowdhury NN , Rhome R, Fishel ML . Frontiers in Oncology.2021;11. CrossRef

- Repurposing Drugs for Overcoming Therapy Resistance in Colon Cancer – A Review Darvishi M, Chekeni AM , Fazelhosseini M, Iqbal Z, Mirza MA , Aslam M, Bayrakdar ETA . Journal of Angiotherapy.2024;8(2). CrossRef

- Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptotic Effect of 7-(4-(N-substituted carbamoylmethyl) piperazin-1-yl) Ciprofloxacin-derivative on HCT 116 and A549 Cancer Cells Alaaeldin R, Nazmy MH , Abdel-Aziz M, Abuo-Rahma GEA , Fathy M. Anticancer Research.2020;40(5). CrossRef

- Unveiling the Anticancer Potential of a New Ciprofloxacin-Chalcone Hybrid as an Inhibitor of Topoisomerases I & II and Apoptotic Inducer Ali DME , Aziz HA , Bräse S, Al Bahir A, Alkhammash A, Abuo-Rahma GEA , Elshamsy AM , Hashem H, Abdelmagid WM . Molecules (Basel, Switzerland).2024;29(22). CrossRef

- The Assessment of Cytotoxicity, Apoptosis Inducing Activity and Molecular Docking of a new Ciprofloxacin Derivative in Human Leukemic Cells Pashapour N, Dehghan-Nayeri MJ , Babaei E, Khalaj-Kondori M, Mahdavi M. Journal of Fluorescence.2024;34(3). CrossRef

- Determination of Heavy Metals in Freshwater Fishes of the Tigris River in Baghdad Mensoor M, Said A. Fishes.2018;3(2). CrossRef

- The evaluation of antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity of the essential oil extracted from the aerial parts of southernwood herb (Artemisia abrotanum L.) that recently grown in Iraq Almahdawy S, Said AM , Abbas IS , Dawood AH . Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research. 2017;10(10).2025;10(10). CrossRef

- Study of the cytotoxic and genotoxic effects for fractioniated extracts of Convolulus arvensis on bone marrow in mice Said Am , Numan IT , Hamad MN . International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences Received.2013;:303-5.

- In Vitro Anticancer Activity of Novel Ciprofloxacin Mannich Base in Lung Adenocarcinoma and High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer Cell Lines via Attenuating MAPK Signaling Pathway Fawzy MA MA , Abu-Baih RH RH , Abuo-Rahma GEA , Abdel-Rahman IM , El-Sheikh AAK , Nazmy MH . Molecules (Basel, Switzerland).2023;28(3). CrossRef

- Fluoroquinolones Suppress TGF-β and PMA-Induced MMP-9 Production in Cancer Cells: Implications in Repurposing Quinolone Antibiotics for Cancer Treatment Huang CY , Yang JL , Chen JJ , Tai SB , Yeh YH , Liu PF , Lin MW , Chung CL , Chen CL . International Journal of Molecular Sciences.2021;22(21). CrossRef

- Implications of nanotherapeutic advancements to leverage multi-drug resistant breast cancer: The state-of-the-art review Aravindan A, Gupta A, Moorkoth S, Dhas N. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology.2024;100. CrossRef

- MAPK/ERK Signaling Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Moon H, Ro SW . Cancers.2021;13(12). CrossRef

- The clinical KRAS(G12C) inhibitor AMG 510 drives anti-tumour immunity Canon J, Rex K, Saiki AY , Mohr C, Cooke K, Bagal D, Gaida K, et al . Nature.2019;575(7781). CrossRef

- KRASG12C Inhibition with Sotorasib in Advanced Solid Tumors Hong DS , Fakih MG , Strickler JH , Desai J, Durm GA , Shapiro GI , Falchook GS , et al . The New England Journal of Medicine.2020;383(13). CrossRef

- Treatment Strategies for KRAS-Mutated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer O'Sullivan É, Keogh A, Henderson B, Finn SP , Gray SG , Gately K. Cancers.2023;15(6). CrossRef

- Targeting SHP1 and SHP2 to suppress tumors and enhance immunosurveillance Zhao Y, Jiang L. Trends in Cell Biology.2025;35(8). CrossRef

- Targeting KRAS in cancer Singhal A, Li BT , O'Reilly EM . Nature Medicine.2024;30(4). CrossRef

- ERK pathway agonism for cancer therapy: evidence, insights, and a target discovery framework Timofeev O, Giron P, Lawo S, Pichler M, Noeparast M. NPJ precision oncology.2024;8(1). CrossRef

- Loss of E-cadherin Activates EGFR-MEK/ERK Signaling, Promoting Cervical Cancer Progression Yun H, Han GH , Wee DJ , Chay DB , Chung JY , Kim JH , Cho H. Cancer Genomics & Proteomics.2025;22(2). CrossRef

- c-Myc-PD-L1 Axis Sustained Gemcitabine-Resistance in Pancreatic Cancer Yao J, Huang M, Shen Q, Ding M, Yu S, Guo Y, Lin Y, et al . Frontiers in Pharmacology.2022;13. CrossRef

- Nuclear ERK: Mechanism of Translocation, Substrates, and Role in Cancer Maik-Rachline G, Hacohen-Lev-Ran A, Seger R. International Journal of Molecular Sciences.2019;20(5). CrossRef

- ERK Inhibitor Ulixertinib Inhibits High-Risk Neuroblastoma Growth In Vitro and In Vivo Yu Y, Zhao Y, Choi J, Shi Z, Guo L, Elizarraras J, Gu A, et al . Cancers.2022;14(22). CrossRef

- Effects of ERK1/2 Inhibitors on the Growth of Acute Leukemia Cells Itoh M, Tohda S. Anticancer Research.2024;44(12). CrossRef

- A phase 1b study of the ERK inhibitor MK-8353 plus pembrolizumab in patients with advanced solid tumors Lakhani NJ , Burris H, Miller WH , Huang M, Chen LC , Siu LL . Investigational New Drugs.2024;42(5). CrossRef

- Sotorasib in KRAS p.G12C-Mutated Advanced Pancreatic Cancer Strickler JH , Satake H, George TJ , Yaeger R, Hollebecque A, Garrido-Laguna I, Schuler M, et al . The New England Journal of Medicine.2023;388(1). CrossRef

- Adagrasib in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Harboring a KRASG12C Mutation Jänne PA , Riely GJ , Gadgeel SM , Heist RS , Ou SHI , Pacheco JM , Johnson ML , et al . The New England Journal of Medicine.2022;387(2). CrossRef

- Single-Agent Divarasib (GDC-6036) in Solid Tumors with a KRAS G12C Mutation Sacher A, LoRusso P, Patel MR , Miller WH , Garralda E , Forster MD , Santoro A, et al . The New England Journal of Medicine.2023;389(8). CrossRef

- Effect of Laetrile Vinblastine Combination on the Proliferation of the Hela Cancer Cell Line Yasin YS , Jumaa AH , Jabbar S, Abdulkareem AH . Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP.2023;24(12). CrossRef

- Saboowala HK. What HeLa Cells aka Immortal Cells Are and Why They Are Important. An Example of Racism in Medicine: Dr. Hakim Saboowala; 2022 Saboowaia HK . .

- HeLa cell culture: Immortal heritage of henrietta lacks Lyapun I, Andryukov B, Bynina M. Molecular Genetics, Microbiology and Virology.2019;34(4):195-200. CrossRef

- In vitro periodontal ligament cell expansion by co-culture method and formation of multi-layered periodontal ligament-derived cell sheets Safi IN , Mohammed Ali Hussein B, Al-Shammari AM . Regenerative Therapy.2019;11. CrossRef

- Cell line authentication: a necessity for reproducible biomedical research Souren NY , Fusenig NE , Heck S, Dirks WG , Capes-Davis A, Bianchini F, Plass C. The EMBO journal.2022;41(14). CrossRef

- The changing 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of cisplatin: a pilot study on the artifacts of the MTT assay and the precise measurement of density-dependent chemoresistance in ovarian cancer He Y, Zhu Q, Chen M, Huang Q, Wang W, Li Q, Huang Y, Di W. Oncotarget.2016;7(43). CrossRef

- Chemical composition, Evaluation of Antiparasitary and Cytotoxic Activity of the essential oil of Psidium brownianum MART EX. DC Bezerra JN , Gomez MCV , Rolon M, Coronel C, Almeida-Bezerra JW , Fidelis KR , et al . Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology.2025;39:102247. CrossRef

- PLIP: fully automated protein-ligand interaction profiler Salentin S, Schreiber S, Haupt JV , Adasme MF , Schroeder M. Nucleic Acids Research.2015;43(W1). CrossRef

- Recent Advances in Molecular Docking for the Research and Discovery of Potential Marine Drugs Chen G, Seukep AJ , Guo M. Marine Drugs.2020;18(11). CrossRef

- Charting the Fragmented Landscape of Drug Synergy Meyer GT , Wooten DJ , Lopez CF , Quaranta V. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences.2020;41(4). CrossRef

- Chou T-CJS. The combination index (CI< 1) as the definition of synergism and of synergy claims. Elsevier; 2018. p. 49-50. Chou TCJS . .

- Cary NJSIIU. Statistical analysis system, User's guide. Statistical. Version 9. 2012 Cary NJSIIU . .

- Sotorasib: First Approval Blair HA . Drugs.2021;81(13). CrossRef

- Abstract PR-15: Identifying synergistic combinations with KRAS inhibition in PDAC | Request PDF ResearchGate.2025.

- Interaction Effect of Methotrexate and Aspirin on MCF7 cell line Proliferation: In vitro Study Mahdi HM , Wadee SA . Journal of Advanced Veterinary Research.2023;13(9).

- Diabetic wound healing enhancement by tadalafil Jarad A. Int J Pharm Res.2020;12(3):841-7. CrossRef

- Evaluation of LH, FSH, Oestradiol, Prolactin and Tumour Markers CEA and CA-125 in Sera of Iraqi Patients With Endometrial Cancer Dawood YJ , Mahdi MA , Jumaa AH , Saad R, Khadim RM . Scripta Medica.2024;55(4). CrossRef

- Targeting Extracellular Signal-Regulated Protein Kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) in Cancer: An Update on Pharmacological Small-Molecule Inhibitors Fu L, Chen S, He G, Chen Y, Liu B. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry.2022;65(20). CrossRef

- Overcoming Resistance to Anti-EGFR Therapy in Colorectal Cancer Dienstmann R, Salazar R, Tabernero J. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Annual Meeting.2015. CrossRef

- Current Development Status of MEK Inhibitors Cheng Y, Tian H. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland).2017;22(10). CrossRef

- Metronidazole affects breast cancer cell lines Sadowska A, Prokopiuk S, Miltyk W, Surazynski A, Kononczuk J, Sawicka D, et al . Advances in medical sciences.2013;58(1):90-5. CrossRef

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright

© Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Biology , 2026

Author Details