The Effect of EPS of Biofilm on Expression of Bax and Bcl-2 Genes in Human Cervical Carcinoma Cell Line (HeLa)

Download

Abstract

Background: The third most common malignancy in women is cervical carcinoma (CC). worldwide and remains a major reason of cancer-related losses. between females. Even though the availability of conventional therapies, their efficacy is often limited, which has encouraged the search for novel agents that selectively target cancer cells. Recent studies suggest that bacterial biofilms may possess anticancer activity.

Objective: Establish exopolysaccharides (EPS) as promising candidates for natural, cost-effective, and biologically compatible cancer therapies.

Methods: In this study, the cytotoxic influence of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) derived from Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms was assessed on HeLa cervical cancer cells via the methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) test to calculate the IC50, or half-maximal inhibitory concentration. Following EPS treatment, apoptotic markers were analyzed by real-time PCR.

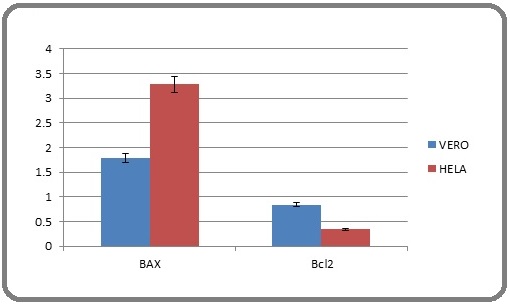

Results: EPS exposure led to a significant, dose-dependent inhibition of HeLa cell proliferation matched to Vero cells (p<0.05). Furthermore, cervical cancer cells treated with EPS exhibited a marked rise in the expression of the pro-apoptotic gene Bax and a concomitant reduction in the expression of the anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2 (p<0.05).

Conclusion: These outcomes indicate that EPS can induce apoptosis in HeLa cells, as reflected by the upregulation of Bax and the downregulation of Bcl-2. This highlights the potential of EPS such as a promising candidate for the development of novel anticancer therapies for cervical cancer.

Introduction

Approximately 70% of cervical cancers originate from abnormal cellular growth within the cervical epithelium, often beginning at the transformation zone near the top of the cervix, which makes early detection challenging. Multiple factors are associated with a heightened threat of growing cervical cancer, such as human papillomavirus (HPV) sickness tobacco use, compromised immune function, and early sexual activity, particularly involving multiple partners [1]. Although significant progress in surgical techniques, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy has led to improved survival rates, and monoclonal antibody treatments, a significant proportion of patients still face the danger of recurrence or mortality [2]. In recent years, bacteria-mediated malignant tumor therapy has emerged such as a promising field of interest due to its unique advantages [3].

The therapeutic use of bacteria against tumors has been investigated for more than a century [4]. As early as 1923, William B. Coley, a pioneer bone surgeon, reported tumor regression in sarcoma patients following injections of heat-inactivated Streptococcus pyogenes, laying the foundation for bacteriotherapy in oncology [5, 6]. The levels of apoptotic expression regulatory proteins, including Bcl-2 and Bax have recently been identified as a critical factor in the induction of apoptosis in cancer cells [7]. Proteins belonging to the Bcl-2 family serve a central role in governing programmed cell death and are essential for maintaining tissue homeostasis; alterations or mutations in these proteins are frequently associated with tumor development [4, 5]. Modulating the cell cycle through the regulation of Both the pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins within the Bcl-2 family.

Specifically, Bcl-2 acts to suppress apoptosis, whereas Bax promotes apoptotic signaling pathways [8].

Advances in medical biotechnology have increased interest in bacteria-mediated cancer therapy (BMCT) as a novel therapeutic strategy [9]. Several bacterial genera, including Salmonella, Bifidobacterium, Clostridium, and Streptococcus, have been extensively studied for their potential antitumor activity. Within this context, Bacterial biofilms are organized societies of microorganisms that stick to surfaces and are surrounded through a self-generated extracellular polymeric substance have attracted significant attention [4]. Exopolysaccharides (EPS), which constitute the major structural component of biofilm matrices, account for approximately 50– 90% of the total organic carbon content. While the chemical and physical properties of EPS differ across bacterial species, polysaccharides remain the dominant constituents [10]. Research conducted by Suresh Kumar, Mody, and Jha 2007 demonstrated that extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) are vital components of the defense mechanisms in algae, fungi, and bacteria [11]. Furthermore, bacterial EPS extracts have been shown to exert antitumor activity by inducing apoptosis in several cancer cell lines. Their strong anticancer, immunomodulatory, and antioxidant properties suggest that EPS may serve as a promising candidate for the development of novel cancer therapeutics [10]. Considerable attention has also been directed toward identifying apoptotic biomarkers as potential targets for advanced cancer treatment [9].

The Bcl-2 gene family shows a pivotal role in controlling apoptotic pathways. As reported by Kunac et al. [12], function to inhibit programmed cell death, whereas others, including Bax, promote apoptotic signaling. As tumor progression advances, a decline in anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein expression is often observed, supporting the concept that early downregulation of these proteins allows survival of cells harboring otherwise lethal mutations. With further oncogenic stimulation, tumor cells may develop additional mechanisms to evade apoptosis [13]. At certain stages of tumor progression, the loss of Bcl-2 function may confer a proliferative advantage to malignant cells. Previous investigations have presented that Bcl-2 displays a role in suppressing cell division [8]. Consequently, its expression tends to be elevated in low-grade or early-stage cancers, which are typically characterized by reduced apoptotic activity, but declines in aggressive or advanced tumors where apoptosis is more pronounced [14]. The connection between apoptotic mechanisms particularly the mitochondrial release of cytochrome C and therapeutic strategies targeting programmed cell death has been extensively investigated [14]. This regulatory pathway is largely governed by the interplay between anti-apoptotic proteins from the Bcl-2 family and pro-apoptotic proteins like Bax [8].

The aim of study to investigating bacterial exopolysaccharides (EPS) as an anticancer agent aims to develop safer and more effective alternatives to conventional chemotherapy, reducing side effects and overcoming drug resistance. Ultimately, the target is to establish EPS as promising candidates for natural, cost-effective, and biologically compatible cancer therapies.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strain and Culture medium

Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC® 27853 for this study, the strain was cultured either on tryptic soy agar (TSA) (Himedia,India) plates or in tryptic soy broth (TSB) at 37 °C. Media were prepared following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Detection of biofilm formation

Microtiter plate test (Quantitative biofilm formation)

Biofilm development was assessed through a microtiter plate adherence assay.. Each well of the 96-well plate received 200 µl of tryptic soy broth. Overnight-grown stationary-phase bacterial cells were diluted at a ratio of 1:100 in new medium before being administered to the wells. The plates were incubated for twenty-four hours at 37°C. Subsequent incubation, wells were gently washed by deionized water to remove non-adherent cells and air-dried under laminar flow for 30 minutes. The adhering biofilms were stained for 30 minutes using a 0.1% crystal violet solution (200 µl/well) (Thomas Baker, India). Excess stain was removed, and the bound dye was solubilized with 300 µl of 70% ethanol) (Thomas Baker, India). The solution obtained was moved into a clean plate for absorbance measurement at 590 nm to determine biofilm biomass [15].

Congo Red Agar Method

As an alternative qualitative method, biofilm-producing bacteria were grown on Congo red agar (CRA) (Himedia,India). The CRA medium was formulated from BHI broth with the addition of 5% sucrose and Congo red. Bacterial colonies forming on this medium were examined for characteristic black or dark red coloration and morphology, indicative of biofilm formation [16].

Development of a Mature Biofilm of Pseudomonas aeruginosa

For the purification of EPS, biofilms were established by transferring 20 mL of anvernight Pseudomonas aeruginosa culture (OD600=0.5) into 400 mL of tryptic soy broth (TSB) freshly prepared and enriched with (0.25-4) % glucose. The cultures were grown in 1.5 L Fernbach flasks, which provided an extensive surface area to promote biofilm adherence. Incubation was carried out at 37 °C under static conditions for 4–5 days, allowing the formation of a thick biofilm matrix [17].

Extraction of Crude Exopolysaccharides (EPS)

Biofilm-matured cultures were centrifuged for 15 minutes at 4 °C and 3,500 g to extract the cell pellets. Any leftover cells and proteins were eliminated after the supernatant was treated with 5% trichloroacetic acid (Thomas Baker, India) and left at 4°C for the entire night. A second centrifugation at 3,500 g was followed by the addition of three liters of 95% ethanol (Thomas Baker,India), 0.1 M NaOH (Thomas Baker, India) to bring the supernatant’s pH down to 7.0, and an overnight incubation at 4 °C to achieve EPS precipitation. After recovering the precipitate (3.500 g, 20 min, 4 °C) by centrifugation, two acetone (Thomas Baker, India) washes, ether dehydration, desiccator drying, weighing, and room temperature storage were performed [18].

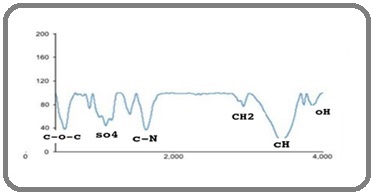

Characterization of EPS

The dried EPS Attenuated total reflection Fourier- transform infrared (FTIR-ATR) (Shimadzu,Japan) spectroscopy was used to analyze the samples. Spectra were recorded in transmittance mode over the range of (400–4,000) cm-1 [18, 19].

Preparation of EPS Extract for Treatment

To prepare EPS solutions for biological assays, the dried biofilm extract was dissolved in sterile DMSO (Thomas Baker, India), filtered twice through filter paper, and sterilized using a 0.22µm membrane filter. Serial dilutions were subsequently conducted using a 640 µg/ ml stock solution to obtain the desired experimental concentrations.

In Vitro Experimental Cell Culture and Treatment Procedures

The effect of bacterial EPS extracts on cell survival was examined using Vero cells, a normal cell type, and HeLa cells, which are used to study human cervical cancer. The Iranian Pasteur Institute supplied them. Following standard culture procedures, the cells were grown at 37 °C in a humidified environment with 5% CO2 in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Fisher Scientific (Austria) GmbH), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Fisher Scientific (Austria) GmbH). The investigations were conducted on cells that were in the logarithmic phase of growth. All investigations were conducted using cells in the logarithmic growth phase, in accordance with previously published protocols [20].

Assay for Cell Viability

The MTT test was used to measure cell growth, according to previously published methods [21].

Primer Preparation for RT-PCR

Lyophilized primers were reconstituted in 300 µl of Enzyme-free water to generate a working reserve solution with a final concentration of 100 pmol /µl, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Microgen, South Korea). A working stock of primers adjusted to 10 pmol/µl, 90 µl of nuclease-free water (Fisher Scientific (Austria) GmbH), and 10 µl of stock were combined to create the solution, which was then stored at -20 °C. Sense and antisense primer sequences for RT-PCR were selected based on previously published studies. Table 1 provides a summary of the sequences used in this study.

| Oligo Name | Primer seq. (5-3) | Reference |

| GAPDH | F 5'-'TGAAGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTGGTC-3 | [22] |

| R 5'-CATGTAGGCCATGAGGTCCACCAC-3' | ||

| Bcl-2 | F 5′-ATCTTCTCCTTCCAGCCTGA-3′ | [23] |

| R 5′TGCAGCTGACTGGACATCTC3′ | ||

| Bax | F5′-CTGCAGAGGATGATTGCTGA-3′R 5′GAGGAAGTCCAGTGTCCAGC-3′ | [23] |

RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

As described previously in reference [24], RNA isolation and subsequent cDNA synthesis were carried out.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (BioRad USA) amplification was carried out in real time. Table 2 lists all of the primer genes that were utilized in the PCR amplification of GAPDH, which was done as a housekeeping gene, utilizing forward and reverse primers. The expression was determined through quantification by gene expression was quantified shown as fold change and calculated using The relative standard curve approach [25].

Statistical Analysis

To examine the differences between data from the treatment and control groups, a one-way ANOVA was employed. (p<0.05) was used to determine statistical significance, and all data were displayed as mean ±SD.

Results

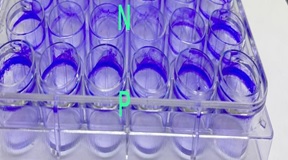

Significant biofilm formation was detected using the TCP assay. Results were deemed (p<0.05) is considered statistically significant. The mean optical density (OD) was used for analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Positive Control B) was 0.3168, whereas the uninoculated medium (Negative Control A) exhibited a mean OD of 0.0912 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Using crystal violet staining in a 96-well tissue culture plate, high and non-slime biofilm producers were identified throughout the TCP technique screening process.

N (Negative), P (Positive) By Congo Red Agar (CRA) technique

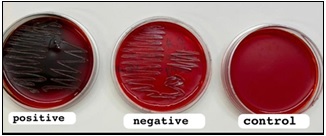

An overnight culture of Pseudomonas aeruginosa was used to inoculate a pleat of Congo red agar (CRA). After being incubated for 24 to 48 hours at 37 °C, colonies showing a black, dry, crystalline morphology after (24-48) hours of incubation at 37 °C were considered positive for biofilm formation, while negative results did not display this characteristic. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Congo Red Agar method show positive of biofilm of P. aeruginosa (Black colonies).

The EPS of biofilm description

Pseudomonas aeruginosa can develop biofilms on the base of culture flasks. Following a four day incubation period at 37 °C, substantial bacterial growth was observed on TSB agar (Himedia, India), with colonies appearing opaque, off-white and exhibiting a mucoid texture. The crude extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) was obtained from P. aeruginosa grown to the stationary phase under optimal conditions and was subsequently separated and refined.as described in the section on Materials and Methods.

Analysis of the EPS extract

FTIR spectroscopy analysis of the EPS revealed several characteristic peaks corresponding to its main functional groups (Figure 3). A broad band between (4000–3500) cm-1 was attributed to O–H stretching vibrations. Bands observed at (2800–3000) cm-1 indicated lipid residues (CH, CH, CH ) as well as contributions from protein amide groups (C=O, N–H, C–N, corresponding to amide I and II). The sulfate functional group (SO) was detected in the (1800–1000) cm-1 region, while polysaccharides and nucleic acids, including C–O, C–O–C, and N–H (amide III) groups, were identified in the (900–125) cm-1 range. Overall, FTIR spectroscopy confirmed the EPS contained various functional groups, including a sulfur containing moiety (Figure 3).

Figure 3. FTIR Spectroscopy was Used to Identify the Main Functional Groups of EPS. Wave number (cm-1) IR Spectrum of EPS from P. aeruginosa biofilm.

Treatment with varying concentrations of EPS extract led to a marked increase in apoptotic cells, accompanied by a significant, dose-dependent reduction in overall cell viability and survival rates. The viability of Vero cells was influenced by exposure to EPS derived from P. aeruginosa biofilms with increasing dose. Cells treated with the lowest concentration (20 µg/ml) exhibited the highest viability, whereas the highest concentration (640 µg/ml) resulted in the greatest reduction in cell viability. Overall, EPS treatment produced a significant inhibitory effect on Vero cell proliferation (Table 2). No significant time-dependent differences in viability were observed, as summarized in (Table 2).

| Concentrations (µg/ml) | Viability percentage % Vero 24h |

| 0 | 100±.00 |

| 20 | 84.302±0.68 |

| 80 | 61.387±8.44 |

| 160 | 55.865±11.80 |

| 320 | 39.454± 18.81 |

| 640 | 20.311±0. 46 |

Notably significant changes were detected in the viability of HeLa cells following treatment with EPS, showing a clear dose-dependent response (Table 3).

| Concentrations EPS (µg/ml) | Viability percentage % HeLa 24h |

| 0 | 100±.00 |

| 20 | 57.065±0.68 |

| 80 | 39.72±8.44 |

| 160 | 28.57±11.80 |

| 320 | 24.777± 18.81 |

| 640 | 23.33±0. 46 |

All data of result given as mean values ± SD (n=3) indicate a statistically significant difference (p<0.05) between groups subjected to treatment and those under control conditions.

After 24 hours of exposure, the highest cell viability was recorded at the lowest concentration (20 µg/ml), whereas the lowest viability occurred at 640 µg/ml. EPS treatment produced a pronounced inhibitory effect on the HeLa cell population (Table 3). and marked differences in cell viability were evident across the various treatment concentrations at the 24 hour time point.

The EPS concentrations Required to inhibit both the growth and proliferation of Vero and HeLa cell lines were determined based on IC50 values derived from dose–response curves using MS Excel. The IC50 for Vero cells was 297.72 µg/ml, while HeLa cells displayed a lower IC50 of 148.39 µg/ml, indicating greater susceptibility to EPS treatment. Notable differences in IC50 values between the two cell lines were also observed (Table 4).

| Cell line | IC 50 (µg/ml) |

| Vero | 297.7248±.784 * |

| HeLa | 148.3851±1 * |

Vero and HeLa cells were exposed to IC50 doses for 24 hours in order to assess the effect of EPS on gene expression, with a particular focus on the BAX and Bcl-2 genes (Figure 4). To create first- strand cDNA, total RNA was taken out of the treated cells and reverse-transcribed. To determine the relative levels of gene expression, quantitative PCR (qPCR) was carried out using the SYBR Green master mix and the cDNA templates and gene specific primers. The ΔΔCT technique (p<0.05) was used to calculate relative expression after normalizing the data against the GAPDH housekeeping gene. Three duplicates of each experiment were conducted to ensure repeatability. The results indicated that EPS treatment increased BAX gene expression in both Vero and HeLa cells compared to their respective controls (Figure 4). The effect was more pronounced in HeLa cells, demonstrating a stronger response to EPS treatment relative to Vero cells. The findings demonstrated that EPS treatment significantly reduced Bcl-2 gene expression in HeLa cells Relative onto the corresponding group under control (p<0.05). By comparison, Vero cells exhibited a comparatively smaller decrease in Bcl-2 expression following EPS exposure (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Demonstrate the Relative Expression of BAX and Bcl2 Ratio in Vero and HeLa .

Discussion

The present findings highlight the pivotal role of bacterial exopolysaccharides (EPS) in modulating apoptotic signaling in human cervical cancer cells. EPS, as the major structural component of microbial biofilms, constitutes up to 90% of the total organic carbon within the matrix, where polysaccharides dominate its composition [11]. Beyond their ecological role in microbial defense, accumulating evidence supports their therapeutic relevance, particularly as anticancer agents [18]. The findings of our study indicate that EPS induces apoptosis in HeLa cells, with this effect being mediated by altering the balance of Bcl-2 family proteins, with significant Bax upregulation accompanied via downregulating Bcl-2.caused the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio to rise, a well-established hallmark of mitochondrial pathway activation. This observation suggests that EPS can trigger intrinsic apoptosis and thereby suppress tumor cell sustained existence.

These results are consistent with research reporting the cytotoxic potential of EPS derived from bacterial sources. For example, Exposure to EPS has been reported to inhibit proliferation and trigger apoptosis in HepG2 cells, while maintaining selectivity toward malignant phenotypes under optimized conditions [19]. Similarly Nami et al., found that EPS secreted by E. lactis IW5 preserved the viability of nearly 95% of normal cells [26], reinforcing the notion that EPS selectively targets cancer cells while sparing healthy counterparts. Such selectivity is of significant therapeutic importance, as it reduces the likelihood of off-target toxicity a major limitation of conventional chemotherapies.

Taken together, these findings position bacterial EPS as a promising bioactive compound for cancer treatment. By modulating apoptotic regulators such as Bax and Bcl-2, EPS may act as a natural apoptosis inducer [27], offering a potential strategy for the creation of anticancer treatments that are both safe and efficient. Further studies are warranted to delineate the signaling pathways involved and to evaluate the effectiveness of EPS in in vivo cancer models.

Also these findings are consistent with prior research demonstrating that natural compounds, especially microbial-derived metabolites, can influence apoptotic signaling and suppress tumor progression [3]. The observed regulatory effect of EPS on apoptosis-related genes underscores its relevance as a therapeutic candidate. Importantly, the bioactivity of EPS is closely linked to its chemical composition. Studies have reported that EPS enriched with sugars, uronic acids, and sulfate groups can exhibit strong anticancer activity [27, 28]. Anionic EPS, carrying phosphate, uronic acid, and sulfate residues, have been shown to interact with tumor-secreted epidermal growth factor (EGF) and inhibit EGF receptor phosphorylation, thereby disrupting proliferative signaling cascades [29]. This is corroborated by the finding that EPS at 300 µg/ml caused cytotoxicity in U87MG glioblastoma cells, with an IC50 of 234.04 µg/ml. while EPS derived from Bacillus species selectively targeted the breast cancer cell line, which is not very harmful to healthy cells [11, 29]. Further evidence supports the selective anticancer properties of EPS from probiotic bacteria [6, 9]. For instance, polysaccharide extracts of Lactobacillus acidophilus (LA- EPS-20079 [30, 31] inhibited colon cancer cell proliferation by approximately 87.27% and induced cell death at nearly 80.65%. Notably, a purified pentasaccharide demonstrated a high selectivity index of 51.3 for cancer cells, underscoring the potent and tumor-specific action of this bacterial metabolite [32]. Such findings reinforce the therapeutic promise of EPS as natural anticancer agents capable of targeting malignant cells while sparing normal tissues. Together, our results, in line with prior studies, suggest that bacterial EPS can act as effective modulators of cancer cell survival by promoting apoptosis and suppressing oncogenic pathways [33]. The observed ability to regulate important genes linked to cell death (Bax and Bcl-2), and impede development factor signaling, supports their role as novel bioactive compounds. These findings not only broaden the understanding of EPS as microbial defense molecules but also highlight their translational potential in oncology. However, further mechanistic studies and in vivo validation are essential to establish their efficacy, safety, and potential clinical application. A crucial checkpoint in the control of apoptosis is provided by proteins belonging to the Bcl-2 family [13], mediating the balance between cell survival and programmed cell death. A high Bax/Bcl-2 ratio is particularly critical, as the promotion of cytochrome c release brought on by MOMP starts the caspase activation cascade. Ultimately leading to cell death. In the current investigation, therapy of HeLa cells with IC₅₀ concentrations of EPS extract for 24 hours significantly upregulated Bax expression while suppressing Bcl-2 expression, thereby elevating. The percentage of Bax to Bcl-2 shifts the balance toward apoptosis. In contrast, minimal alterations in the expression of Bcl-2 and Bax were observed in non-cancerous Vero cells, indicating a degree of selectivity for malignant cells. These findings are consistent with earlier studies reporting that microbial-derived EPS triggers apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway, mediated by Bax upregulation and Bcl-2 downregulation [34]. The ability of EPS to differentially modulate these apoptotic regulators suggests its potential utility as a targeted anticancer agent [35]. Notably, expression levels of Bax and Bcl-2 are considered important prognostic markers in cervical cancer, with Bcl-2 expression providing independent prognostic information on disease progression [7, 36]. Since altering this ratio is a known method for boosting apoptosis in cancer treatment, the observed rise in the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio after EPS treatment in HeLa cells further emphasizes the therapeutic importance of this route [35, 37]. Beyond its role in apoptosis induction, EPS has been widely studied for its antimicrobial and anti-biofilm activities [38]. The present findings extend its biological significance, highlighting its anticancer potential. Importantly, the selective impact on cancer cells, coupled with limited effects on normal cells, supports the feasibility of developing EPS as a therapeutic agent with reduced cytotoxic side effects compared to conventional chemotherapeutics.

Nevertheless, several limitations remain, the current study was confined to in vitro analyses, and additional investigations are required to elucidate the precise molecular mechanisms underlying EPS-mediated apoptosis. In vivo validation using relevant animal models will be essential to confirm its efficacy and safety. Furthermore, exploring the potential of EPS in combination with standard chemotherapeutic agents may provide synergistic benefits, enhancing treatment efficacy and potentially overcoming drug resistance in cervical cancer. In summary, the present study demonstrates that EPS extract induces HeLa cell death through altering the Bax/Bcl-2 signaling pathway, thereby highlighting its therapeutic promise as a novel anticancer strategy. These findings contribute to the growing evidence supporting microbial EPS as a valuable bioactive compound, warranting further investigation for its integration into future cancer treatment regimens.

In conclusion, the findings emphasize how important the Bax and Bcl-2 genes are in triggering apoptosis after EPS extract administration. The decrease of Bcl-2 and the observed increase in Bax levels imply that EPS causes cell death via the apoptotic pathway. These results show that EPS has the potential to be a novel therapeutic method and provide opportunities for further research on its use as a therapeutic intervention for cervical cancer in humans.

Conflict of Interest

Regarding this publication, the authors affirm that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Diagnosis, staging, and surveillance of cervical carcinoma Kaur H, Silverman PM , Iyer RB , Verschraegen CF , Eifel PJ , Charnsangavej C. AJR. American journal of roentgenology.2003;180(6). CrossRef

- Cancer Chemotherapy. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Amjad MT , Chidharla A, Kasi A. 27 Feb 2023.

- Use of Bacteria in Cancer Therapy Sarotra P, Medhi B. Recent Results in Cancer Research. Fortschritte Der Krebsforschung. Progres Dans Les Recherches Sur Le Cancer.2016;209. CrossRef

- A Review of Novel Methods of the Treatment of Cancer by Bacteria Kahrarian Z, Horriat M, Khazayel S. Asian Journal of Research in Medicine and Medical Science.2019.

- Bacteria and cancer: cause, coincidence or cure? A review Mager D. Journal of Translational Medicine.2006;4(1):1-18. CrossRef

- Bax and Bcl-2 expressions predict response to radiotherapy in human cervical cancer Harima Y, Harima K, Shikata N, Oka A, Ohnishi T, Tanaka Y. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology.1998;Sep 28;124(9):503–10. CrossRef

- Regulation of Apoptosis in Health and disease: the Balancing Act of BCL-2 Family Proteins Singh R, Letai A, Sarosiek K. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology.2019;20(3):175-93. CrossRef

- Bacteria-cancer interactions: bacteria-based cancer therapy Duong MTQ , Qin Y, You SH , Min JJ . Experimental & Molecular Medicine.2019;51(12):1-15. CrossRef

- Use of Salmonella Bacteria in Cancer Therapy: Direct, Drug Delivery and Combination Approaches Badie F, Ghandali M, Tabatabaei SN , Safari M, Khorshidi A, Shayestehpour M. Frontiers in Oncology.2021;11(624759). CrossRef

- Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm-Conditioned Medium Impairs Macrophage-Mediated Antibiofilm Immune Response by Upregulating KLF2 Expression Alboslemy T, Yu B, Rogers T, Kim MH . Infection and Immunity.2019;87(4):e00643-18. CrossRef

- Bacterial exopolysaccharides – a perception Suresh Kumar A, Mody K, Jha B. Journal of Basic Microbiology.2007;47(2). CrossRef

- The Expression Pattern of Bcl-2 and Bax in the Tumor and Stromal Cells in Colorectal Carcinoma Kunac N, Filipović N, Kostić S, Vukojević K. Medicina.2022;58(8). CrossRef

- BCL-2 family isoforms in apoptosis and cancer Warren CFA , Wong-Brown MW , Bowden NA . Cell Death & Disease.2019;10(3). CrossRef

- Targeting apoptotic caspases in cancer Boice A, Bouchier-Hayes L. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research.2020;1867(6). CrossRef

- Characterization of exopolysaccharide derived from Enterobacter ludwigii and its possible role as an emulsifier Paikra SK , Panda J, Sahoo G, Mishra M. 3 Biotech.2022;12(9). CrossRef

- Evaluation of different detection methods of biofilm formation in the clinical isolates Hassan A, Usman J, Kaleem F, Omair M, Khalid A, Iqbal M. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases.2011;15(4). CrossRef

- Purification and Characterization of Biofilm-Associated EPS Exopolysaccharides from ESKAPE Organisms and Other Pathogens Bales PM , Renke EM , May SL , Shen Y, Nelson DC . PLoS ONE.2013;8(6). CrossRef

- Antitumor Exopolysaccharides Derived from Novel Marine Bacillus: Isolation, Characterization Aspect and Biological Activity Abdelnasser SM , M Yahya SM , Mohamed WF , S Asker MM , Abu Shady HM , Mahmoud MG , Gadallah MA . Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention.2017;18(7). CrossRef

- Physicochemical Properties of Extracellular Polymeric Substances Produced by Three Bacterial Isolates From Biofouled Reverse Osmosis Membranes Rehman ZU , Vrouwenvelder JS , Saikaly PE . Frontiers in Microbiology.2021;12. CrossRef

- Culture of animal cells: a manual of basic technique and specialized applications. 7th ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Freshney RI . 2015.

- Biochemical Analysis of Apoptosis to Impact of Bacterial Extracellular Polymeric Substances Extract on Human Breast Cancer Cell Line (MCF-7). Surgery Bachay I.A., Suker D.K.. Gastroenterology and Oncology.2025;29(4-Supplement):S80. CrossRef

- The interaction of two intracellular signaling network regulators and their role in cancer Bosso M, RKIP AF . Prognostic and Therapeutic Applications of RKIP in Cancer. Academic Press: United States.2020.

- Induction of Apoptosis in HeLa Cells by a Novel Peptide from Fruiting Bodies of Morchella importuna via the Mitochondrial Apoptotic Pathway Xiong C, Li P, Luo Q, Phan CW , Li Q, Jin X. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine.2021;2021. CrossRef

- Hep88 mAb-Mediated Paraptosis-Like Apoptosis in HepG2 Cells via Downstream Upregulation and Activation of Caspase-3, Caspase-8 and Caspase-9 Mitupatum T, Aree K, Kittisenachai S, Roytrakul S, Puthong S, Kangsadalampai S. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention.2015;16(5):1771-9. CrossRef

- Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method Livak KJ , Schmittgen TD . Methods.2001;Dec;25(4):402–8. CrossRef

- Molecular Identification and Probiotic Potential Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Human Vaginal Microbiota Nami Y, Haghshenas B, Yari Khosroushahi A. Advanced Pharmaceutical Bulletin.2018;8(4):683–95. CrossRef

- Quantitative expression analysis of the apoptosis-related genes BCL2, BAX and BCL2L12 in gastric adenocarcinoma cells following treatment with the anticancer drugs cisplatin, etoposide and taxol Korbakis D, Scorilas A. Tumor Biology.2012;33(3):865-75. CrossRef

- Functional and cell proliferative properties of an exopolysaccharide produced by Nitratireductor sp Priyanka P, BA AA , Ashwini P, P.D R. PRIM-31. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules.2016;85. CrossRef

- The New Age Chemopreventives: A Comprehensive Review Bhuyan PP , Nayak R, Patra S, Abdulabbas HS , Jena M, Polysaccharides PBS . Cancers.2023;15(3):715-45. CrossRef

- A Study on Characterization of EPS and Media Optimization for Bacterial Calcium Carbonate Precipitation Priya JN , Kannan M, Priyanka P, Mary SV . International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences.2016;5(4):590-5. CrossRef

- A novel purified Lactobacillus acidophilus 20079 exopolysaccharide, LA-EPS-20079, molecularly regulates both apoptotic and NF-κB inflammatory pathways in human colon cancer El-Deeb NM , Yassin AM , Al-Madboly LA , El-Hawiet A. Microbial Cell Factories.2018;17(1). CrossRef

- Apoptosis of Human Breast Cancer Cells (MCF-7) Induced by Polysacccharides Produced by Bacteria Vidhyalakshmi R. Journal of Cancer Science & Therapy.2013;05(02). CrossRef

- Bacteria in cancer therapy: a novel experimental strategy Patyar S, Joshi R, Byrav DP , Prakash A, Medhi B, Das BK . Journal of Biomedical Science.2010;17(1). CrossRef

- Targeting apoptosis in cancer therapy Carneiro BA , El-Deiry WS . Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology.2020;17(7). CrossRef

- Apoptosis and Molecular Targeting Therapy in Cancer Hassan M, Watari H, AbuAlmaaty A, Ohba Y, Sakuragi N. BioMed Research International.2014;2014. CrossRef

- Purification, partial characterization and antitumor effect of an exopolysaccharide from Rhizopus nigricans Yu W, Chen G, Zhang P, Chen K. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules.2016;82. CrossRef

- The Possible Role of p53 and bcl-2 Expression in Cervical Carcinomas and Their Premalignant Lesions Dimitrakakis C, Kymionis G, Diakomanolis E, Papaspyrou I, Rodolakis A, Arzimanoglou I, Leandros E, Michalas S. Gynecologic Oncology.2000;77(1). CrossRef

- Exopolysaccharide production by a marine Pseudoalteromonas sp. strain isolated from Madeira Archipelago ocean sediments Roca C, Lehmann M, Torres CA , Baptista S, Gaudêncio SP , Freitas F, Reis MA . New Biotechnology.2016;33(4). CrossRef

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright

© Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Biology , 2026

Author Details