Lunasin‑Rich Soybean Extract Attenuates MMP‑9 Expression in an AOM/DSS Mouse Model of Colitis‑Associated Colorectal Cancer

Download

Abstract

Background: Colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks as the third most common malignancy globally and is strongly associated with chronic inflammation, particularly colitis-associated cancer (CAC). Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) is a key enzyme in tumor invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis. Lunasin, a 44–amino acid peptide derived from soybeans, exhibits anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities, but its role in modulating MMP-9 in CAC remains unclear.

Methods: Thirty male Swiss Webster mice (12 weeks, ~25 g) were randomly assigned to six groups: normal control, negative control, positive control, and three lunasin-rich soybean extract (LRSE) groups (250, 300, 350 mg/kg). CAC was induced using a single intraperitoneal injection of azoxymethane (10 mg/kg) followed by 2% dextran sodium sulfate in drinking water for 7 days. Treatments were given orally for 4 weeks. Colon tissues were collected, and MMP-9 expression was assessed by immunohistochemistry and quantified using the H-score. Data were analyzed with Welch’s ANOVA and Games–Howell post hoc test.

Results: Azoxymethane/Dextran sodium sulfate (AOM/DSS) significantly increased MMP-9 expression compared with normal controls (p < 0.001). Aspirin reduced MMP-9 expression relative to the negative control (p = 0.001). LRSE significantly decreased MMP-9 expression at doses of 250 mg/kg (p = 0.048) and 350 mg/kg (p = 0.001), while the 300 mg/kg dose showed no significant effect. The inhibitory effect of LRSE did not display a clear dose–response pattern.

Conclusion: LRSE significantly reduced MMP-9 expression in an AOM/DSS-induced CAC mouse model, supporting its potential as a natural chemopreventive agent. Further research with larger cohorts and molecular pathway analyses is warranted.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer in terms of incidence, with more than 1.9 million new cases expected in 2020. It is also the second most deadly cancer in the world [1]. The incidence of colorectal cancer continues to rise in developing countries such as Eastern Europe, South-East Asia, South-Central Asia and South America. The increase in colorectal cancer incidence has been linked to changes in lifestyle factors, such as changes in diet and sedentary lifestyles leading to reduced physical activity, which can lead to obesity [2, 3]. Other risk factors for developing bowel cancer include heavy alcohol consumption, smoking, and eating red or processed meat [2, 4, 5].

Pharmacoeconomic studies show an upward trend in colorectal cancer-related costs [6]. This is due to the increase in targeted biological therapies [7, 8]. Currently, colorectal cancer therapies include combinations of capecitabine with oxaliplatin (CAPOX), oxaliplatin with 5-fluorouracil and folic acid (FOLFOX), single agent fluoropyrimidine, and surgery [9, 10]. Meanwhile, interventional therapies are toxic invasive therapies that may fail to prevent disease progression to metastasis.

Therefore, the development of colorectal cancer therapies is still ongoing.

One candidate for colorectal cancer prevention therapy is lunasin-rich soybean extract. Lunasin-rich soybean extract is a peptide consisting of 44 amino acids found in soybean plants [11]. It is known that soybean extract containing 0.82 mg/g of lunasin can inhibit carcinogenesis of colon cancer tissue [12]. Anti-inflammatory is the suggested mechanism, which is through suppressing nuclear factor-kappa beta (NF-Kβ) and reducing cyclooxygenase (COX) expression [13]. In addition, lunasin is also able to reduce the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOs), beta-catenin, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) [12, 14]. However, there is no research on the effect of lunasin on MMP-9 expression in colorectal cancer.

MMP-9 is a type of MMP protein in the gelatinase family located on chromosome 20q13.12 in humans [15,16]. MMP-9 proteins play an important role in cancer progression by degrading the extracellular matrix. They play a role in the process of angiogenesis, metastasis and invasion of cancer [15]. Therefore, the objective of this study was to ascertain the impact of administering a soy extract rich in lunasin on the expression of MMP-9 in mouse colon tissue induced with azoxymethane/dextran sodium sulfate (AOM/DSS).

Materials and Methods

Study Design

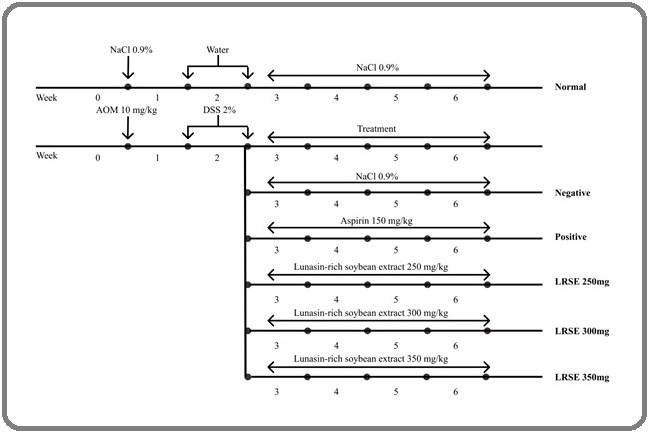

A controlled in vivo experiment was conducted using 12-week-old male Swiss-Webster mice. Colorectal carcinogenesis was induced using a combination of azoxymethane (AOM) and dextran sodium sulfate (DSS). Following carcinogen induction, mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups and received the respective treatments for 4 weeks (see Figure 1 for timeline and protocol).

Figure 1. Timeline and Protocol of the Study.

All experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia (Permit No. KET-028/UN2.F1.D1.2/PDP.01/Riset-2/2022).

Plant Materials and Extraction Techniques

Soybeans of the Grobogan variety were obtained from the Indonesian Legumes and Tuber Crops Research Institute (Malang, East Java, Indonesia). Prior to extraction, the beans were mechanically defatted at the Herbs and Medicinal Plants Research Institute (Bogor, West Java, Indonesia) using a hydraulic press operated at 100–150 atm and 50°C for 30 minutes. The resulting defatted soybeans were dried and milled into a fine powder. A total of 1,250 g of soybean powder was macerated in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a 1:5 (w/v) ratio (6,250 mL) for 60 minutes. The mixture was filtered three times through gauze to remove particulates, and the filtrate was concentrated by evaporation at 50 °C.

Analysis of Lunasin Content

Lunasin content in each extract was quantified using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Prior to analysis, the extracts were diluted with distilled water and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 30 minutes. The supernatant was then filtered through a 0.22 µm membrane filter and injected into an HPLC system equipped with a UV-Vis detector (L-2420) set at 295 nm. Chromatographic separation was carried out using an isocratic mobile phase consisting of 95% distilled water and 5% acetonitrile, with a flow rate of 2 mL/min under a linear gradient program for 35 minutes. Lunasin was identified and quantified by comparing retention times with those of a lunasin standard. Since this study used the same Grobogan soybean extract following earlier study, the lunasin content is comparable to previously reported values [17].

Experimental Animals and Housing Conditions

Twelve-weeks-old male Swiss Webster mice with an average body weight of approximately 25 g were obtained from the Research and Development Agency of the Indonesian Ministry of Health. Prior to the experiment, the mice were acclimated for one week at the Laboratory of Anatomical Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia. They were maintained under standardized conditions, including a temperature of 25 °C, relative humidity of 55%, and a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Standard laboratory chow and water were provided ad libitum. Animal care and handling followed the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee [18]. The health condition of the mice was routinely monitored, including activity level, food and water consumption, and body weight.

Carcinogenesis Induction

Colorectal carcinogenesis was initiated by a single intraperitoneal (IP) injection of AOM at a dose of 10mg/kg body weight, dissolved in 0.9% NaCl, administered during the first week of the study. One week following AOM administration, mice received 2% DSS in their drinking water for seven consecutive days. Animals were then assigned to treatment groups and observed for an additional four weeks.

Mice were randomly divided into six groups (n = 5 per group): normal control, negative control, positive control (aspirin), and three treatment groups receiving LRSE at doses of 250, 300, and 350 mg/kg body weight. One sample in the positive control group was later excluded from analysis due to tissue loss during histological processing. The normal control group received 0.9% NaCl intraperitoneal and no exposure to AOM/DSS. The negative control group underwent AOM/ DSS induction but received no further intervention. The positive control group received aspirin, while the LRSE groups received LRSE orally once daily for four weeks. At the end of the treatment period, all animals were euthanized, and colon tissues were collected for further analysis.

Immunohistochemistry Staining and Analysis

The distal third of the colon was collected, rinsed with sterile saline, and fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin (Merck, Germany) for 24 hours. Tissues were then processed, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 4 µm using a rotary microtome (Leica Biosystems, Germany). Sections were mounted on poly-L-lysine-coated slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and incubated on a slide warmer at 56.5–60 °C for 60 minutes.

Deparaffinization was performed in xylene (three changes, 5 minutes each), followed by rehydration through a graded ethanol series (95% and 80%, 5 minutes each), and rinsing in running tap water for 5 minutes. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubating slides in 0.5% hydrogen peroxide for 30 minutes, followed by washing in running water for 5 minutes.

Antigen retrieval was performed in a citrate buffer (10 mM, pH 6.0) using a microwave oven at high power for 10 minutes. Slides were allowed to cool at room temperature for 30 minutes and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 minutes.

To block non-specific binding, slides were incubated with Sniper blocking reagent (Biocare Medical, USA) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Sections were then incubated with primary antibody against MMP-9 (Abcam, UK) diluted 1:100 in antibody diluent for 60 minutes at room temperature.

After washing with PBS for 10 minutes, slides were incubated with a universal HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 15 minutes, followed by another PBS wash. Detection was performed using TrekAvidin-HRP reagent (Biocare Medical, USA) for 15 minutes at room temperature. Slides were then washed twice in PBS (10 minutes each).

Chromogenic detection was performed using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution for 20–30 seconds, followed by rinsing in running water. Counterstaining was done with Mayer’s hematoxylin for 1–2 minutes, then washed with running water and briefly immersed in saturated lithium carbonate solution for 1 minute. Finally, sections were dehydrated through graded ethanol, cleared in xylene, and mounted with an aqueous mounting medium.

Quantification of MMP-9 Expression

The expression of MMP-9 was assessed based on the intensity of brown immunostaining observed in the cytoplasm of colon epithelial cells. Cells were classified into four categories: high positive (HP, dark brown), moderate positive (MP, medium brown), low positive (LP, light brown), and negative (NC, blue). ImageJ Cell Counter was used to quantify cell counts across five randomly selected high-power fields (400× magnification), analyzed by a blinded observer to minimize bias. The percentage of cells in each category was used to calculate an H-score using the following formula:

H-score = (% HP × 4) + (% MP × 3) + (% LP × 2) + (% NC × 1)

This scoring system provides a semi-quantitative measure of MMP-9 expression in tissue sections.

Statistical Analysis

All data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using Welch’s one-way ANOVA in SPSS version 24.0, followed by the Games–Howell post hoc test to assess differences between treatment groups. Data distribution was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test, which indicated normality (p > 0.05). However, Levene’s test revealed non-homogeneous variances (p < 0.05). Therefore, due to the normal distribution but unequal variances, Welch’s ANOVA and the Games–Howell post hoc test were applied. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

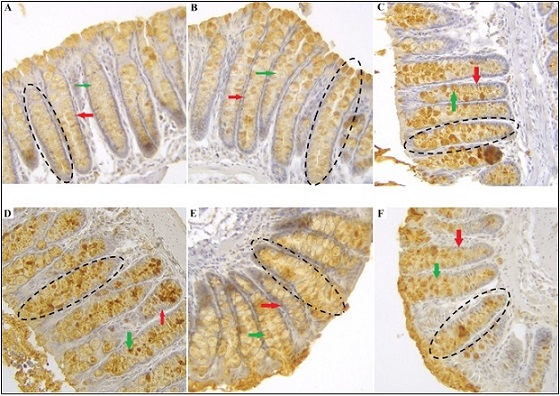

Following immunohistochemical staining, MMP-9 expression in the cytoplasm of mouse colon epithelial cells was indicated by the intensity of brown coloration, with darker staining reflecting higher expression levels. In the normal group, most epithelial cells demonstrated weak brown intensity, often appearing nearly negative. The positive control group predominantly exhibited weak to moderate brown staining, whereas the negative control group showed strong brown intensity. In the lunasin-treated groups, a dose-dependent reduction in staining intensity was observed, with the most pronounced decrease detected at doses of 250 mg/kg, 300 mg/kg, and 350 mg/kg (Figure 2).

Figure 2. MMP-9 Expression in Mouse Colonic Epithelial Cells Immunohistochemically Stained at 400X Magnification. Normal (A); positive control (B); negative control (C); LRSE 250 mg/kg (D), 300 mg/kg (E), and 350 mg/kg (F). The red, green, and dashed black arrows respectively indicate epithelial cells, goblet cells, and crypts of mouse colon tissue.

MMP-9 expression was quantified by calculating the sum and mean Histo Score (H-score) for each group (Table 1).

| Group | N | H-Score (%) | CI 95% | |

| Mean | SD | |||

| Normal | 5 | 107.17 | 1.57 | 105.22 – 109.12 |

| Positive control | 4 | 111.27 | 0.65 | 110.22 – 112.31 |

| Negative control | 5 | 126.48 | 2.96 | 122.81 – 130.15 |

| LRSE 250mg | 5 | 115.78 | 5.27 | 109.22 – 122.32 |

| LRSE 300mg | 5 | 120.55 | 1.05 | 119.25 – 121.86 |

| LRSE 350mg | 5 | 113.25 | 2.24 | 110.46 – 116.03 |

The Shapiro–Wilk test confirmed normal distribution of the data (p > 0.05), whereas Levene’s test indicated heterogeneity of variances (p < 0.05). Given the normal distribution but non-homogeneous variances, statistical analysis was conducted using Welch’s One-Way ANOVA followed by the Games–Howell post hoc test.

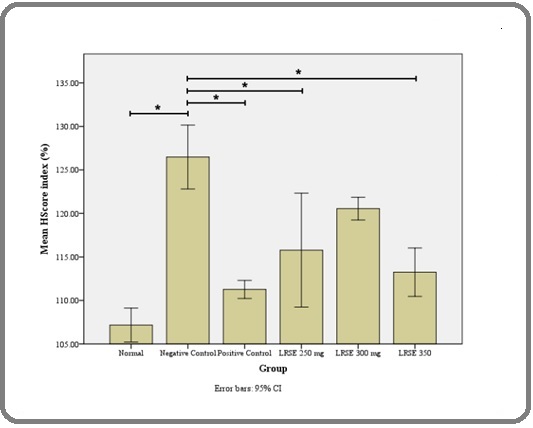

The study demonstrated a statistically significant difference in MMP-9 expression among the groups. Specifically, the negative control group differed significantly from the LRSE 250 mg group (p = 0.048), LRSE 350 mg group (p = 0.001), positive control group (p = 0.001), and the normal group (p < 0.001). The LRSE 300 mg group showed significant differences compared with the LRSE 350 mg group (p = 0.005), positive control group (p < 0.001), and normal group (p < 0.001). Additionally, significant differences were observed between the LRSE 350 mg and normal groups (p = 0.012), as well as between the positive control and normal groups (p = 0.016). These findings are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Mean H-score Index (%) of MMP-9 Expression Across Groups. The negative control group showed significantly higher MMP-9 expression compared with the normal, positive control, LRSE 250 mg, and LRSE 350 mg groups (*p < 0.05). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

The statistical analysis demonstrated a significant difference in MMP-9 expression between the normal and negative control groups (p < 0.001), confirming that AOM injection combined with DSS administration effectively induces colitis-associated cancer (CAC) in mouse colon tissue. This result is consistent with prior studies, including Parang et al. [19], who reported that a single intraperitoneal dose of 1 mg/ml AOM followed by three cycles of 3% DSS induced CAC in C57BL/6 mice. Similarly, other studies have shown that CAC can be established using a single administration of 10 µg/gBW AOM in combination with a cycle of 2.5% DSS [20].

Mechanistically, AOM acts as a procarcinogen that is metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP2E1) into methylazoxymethanol (MAM). MAM forms O6-methylguanine adducts in DNA, resulting in G-to-A transitions. After biliary excretion, these metabolites are absorbed by colonic epithelial cells, initiating mutagenesis. Concurrently, DSS, a heparin-like polysaccharide, disrupts the colonic epithelium when administered in drinking water, mimicking colitis as seen in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [19]. Tumor formation typically occurs within 8–10 weeks following AOM/DSS induction [19, 21].

Chronic inflammation is a key driver of CAC. Enhanced Wnt signaling coupled with elevated pro- inflammatory mediators, such as IL-6, increases c-Myc expression, an oncogene that regulates cell cycle progression [20, 21]. In addition, inflammatory processes alter microRNA expression, activating the PI3K pathway and promoting malignant transformation. Multiple pathways and mediators including NF-κB, JAK/STAT3, TNF-α, IL-6, COX-2, and iNOS; have been implicated in CAC pathogenesis [20]. Early carcinogenic events involve Apc/β-catenin, Kras, and c-Myc activation with global hypermethylation, while COX-2 and iNOS become prominent during adenoma-to-carcinoma progression [21].

NF-κB, in particular, plays a pivotal role in AOM/ DSS-induced tumorigenesis [22]. It regulates the expression of cytokines, inflammatory mediators, apoptosis, and cell proliferation. Its activation impedes apoptosis by upregulating anti-apoptotic proteins. Elevated NF-κB levels have been observed in epithelial cells and macrophages of patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease [23]. DSS-induced TNF-α production further amplifies inflammation through activation of the SphK1/NF-κB/STAT3 signaling axis, thereby facilitating tumorigenesis [21].

As a downstream effect, cancer cells secrete interleukins, interferons, growth factors, and extracellular MMP inducers that stimulate host cells to produce MMP-9. This enzyme contributes to invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis by degrading gelatin and collagens (types IV, V, XI, and XVI) [15]. These mechanisms explain the observed increase in MMP-9 expression in mouse colon tissue following AOM/DSS induction.

The Games–Howell post hoc analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in MMP-9 expression between the positive control and negative control groups (p = 0.001), indicating that aspirin effectively reduces MMP-9 expression in mouse colon tissue. This finding is consistent with the study by Amalia et al. [17], which demonstrated that administration of aspirin at 150 mg/kg for 4 weeks decreased inflammatory responses, as reflected by a reduction in the incidence of dysplasia in the colonic epithelium of Swiss Webster mice.

At the molecular level, aspirin has been shown to inhibit MMP-9 expression through multiple mechanisms. Xue et al. [24] reported that aspirin suppresses MMP-9 mRNA expression and protein release by enhancing PPARα/γ signaling while reducing COX-2/mPGES-1 signaling in macrophages derived from THP-1 cells. In addition, aspirin was found to upregulate tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMP-1 and TIMP-2), further contributing to MMP-9 inhibition in both cultured mouse colon macrophages and ox-LDL-stimulated human monocyte–derived macrophages [24, 25].

Another mechanism involves modulation of NF- κB signaling. Hua et al. [26] observed that aspirin administration decreased NF-κB expression in ox-LDL- stimulated macrophages. This effect is thought to occur via COX-independent pathways, including the inhibition of IκB kinase (IKK) β, thereby preventing NF-κB activation, as demonstrated in both in vivo and in vitro studies [27,28]. Additional reports further support aspirin’s anti- inflammatory actions, showing that it can suppress NF-κB signaling through TLR4 receptor inhibition, downregulate IL-6 expression via STAT3 signaling, and attenuate both COX/PGE2 and Wnt pathways [29-32].

The administration of LRSE demonstrated a significant effect on MMP-9 expression. This was evident from the comparison between the negative control and the LRSE 250 mg group (p = 0.048) as well as the LRSE 350 mg group (p = 0.001). These findings suggest that lunasin supplementation reduces MMP-9 expression in AOM/DSS-induced Swiss Webster mouse colon tissue. However, no significant difference was observed between the negative control and the LRSE 300 mg group, indicating that the inhibitory effect on MMP-9 expression may not follow a strict dose–response pattern.

Soybean was selected as the source of lunasin in this study because it contains the highest concentrations of the peptide, ranging from 0.5 to 8.1 mg/g [33]. Lunasin is a 44–amino acid peptide with three functional domains: the aspartic acid tail, the RGD (Arg–Gly–Asp) domain, and the chromatin-binding helical domain. Among these, the RGD domain is critical for cellular internalization and modulation of integrin-mediated signaling [11, 33, 34].

Lunasin has been identified as a promising anticancer agent due to its ability to suppress tumor progression by downregulating MMP-9 expression. Jiang et al. [35] reported that lunasin inhibited breast cancer cell migration and invasion by suppressing both MMP-2 and MMP-9 through FAK/Akt/ERK and NF-κB signaling pathways. Similarly, studies have shown that lunasin can bind integrin α5β1 via its RGD motif, resulting in suppression of FAK/ERK/NF-κB signaling in KM12L4 colon cancer cells [36].

FAK, a non-receptor tyrosine kinase, is a key mediator of integrin signaling. Upon extracellular matrix binding, integrins recruit and activate FAK via autophosphorylation. Activated FAK triggers downstream signaling cascades, including ERK phosphorylation. ERK then activates IκB kinase (IKK), which phosphorylates IκB, leading to its ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. This process releases the NF-κB/Rel complex, allowing NF-κB to translocate into the nucleus. Activated NF-κB regulates apoptosis, proliferation, differentiation, and inflammatory cytokine production, processes that, over time, drive carcinogenesis [23]. Cancer cells further amplify this effect by releasing cytokines, growth factors, and extracellular MMP inducers, which stimulate host cells to produce MMP-9, thereby enhancing invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis [15].

By binding to integrin α5β1, lunasin disrupts the interaction between integrins and extracellular matrix proteins, thereby attenuating FAK activation. This leads to downregulation of ERK signaling and inhibition of the NF-κB pathway. In addition, lunasin has been shown to increase IκB-α expression, further preventing NF-κB activation [36]. Through these mechanisms, lunasin suppresses carcinogenic signaling and reduces MMP-9 expression, consistent with the findings of the present study.

In conclusion, lunasin-rich soybean extract significantly reduced MMP-9 expression in AOM/DSS-induced colitis- associated colorectal cancer (CAC) mouse models, highlighting its potential as a natural chemopreventive agent. These findings warrant further investigation of lunasin as an adjunct or alternative strategy in the prevention and management of CAC.

Originality Declaration for Figures

All figures included in this manuscript are original and have been created by the authors specifically for the purposes of this study. No previously published or copyrighted images have been used. The authors confirm that all graphical elements, illustrations, and visual materials were generated from the data obtained in the course of this research or designed uniquely for this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Originality Declaration for Figures

All figures included in this manuscript are original and have been created by the authors specifically for the purposes of this study. No previously published or copyrighted images have been used. The authors confirm that all graphical elements, illustrations, and visual materials were generated from the data obtained in the course of this research or designed uniquely for this manuscript.

References

- Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL , Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.2021;71(3). CrossRef

- A Review of Colorectal Cancer in Terms of Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Development, Symptoms and Diagnosis Sawicki T, Ruszkowska M, Danielewicz A, Niedźwiedzka E, Arłukowicz T, Przybyłowicz KE . Cancers.2021;13(9). CrossRef

- Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors Rawla P, Sunkara T, Barsouk A. Gastroenterology Review.2019;14(2). CrossRef

- Role of Diet in Colorectal Cancer Incidence: Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses of Prospective Observational Studies Veettil SK , Wong TY , Loo YS , Playdon MC , Lai NM , Giovannucci EL , Chaiyakunapruk N. JAMA Network Open.2021;4(2). CrossRef

- Risk Factors for the Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer Lewandowska A, Rudzki G, Lewandowski T, Stryjkowska-Góra A, Rudzki S. Cancer Control.2022;29. CrossRef

- The Pharmacological Costs of First-Line Therapies in Unselected Patients With Advanced Colorectal Cancer: A Review of Published Phase III Trials Giuliani J, Bonetti A. Clinical Colorectal Cancer.2016;15(4). CrossRef

- Addressing Challenges in Targeted Therapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer El Hage M, Su Z, Linnebacher M. Cancers.2025;17(7). CrossRef

- Comprehensive review of targeted therapy for colorectal cancer Xie Y, Chen Y, Fang J. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy.2020;5(1). CrossRef

- Colorectal cancer: summary of NICE guidance Bromham N, Kallioinen M, Hoskin P, Davies RJ . BMJ.2020. CrossRef

- Metastatic colorectal cancer: Advances in the folate-fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy backbone Glimelius B, Stintzing S, Marshall J, Yoshino T, De Gramont A. Cancer Treatment Reviews.2021;98. CrossRef

- Development of the plant-derived peptide lunasin as an anticancer agent Vuyyuri SB , Shidal C, Davis KR . Current Opinion in Pharmacology.2018;41. CrossRef

- The Effect Of Lunasin From Indonesian Soybean Extract On Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase And Β-Catenin Expression In Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Mice Colon Kusmardi K, Nessa N, Estuningtyas A, Tedjo A, Wuyung PE . Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research.2018;11(1). CrossRef

- Inhibition of Cox-2 Expression by Lunasin-Rich Soybean Extract on Colorectal Cancer Kusmardi K, Karenina V, Estuningtyas A, Tedjo A. International Journal of Applied Pharmaceutics.2019. CrossRef

- Effect Of Lunasin-Rich Soybean Extract Upon Tnf-Α Expression On Colonic Epithelial Cells Of Mice Induced By Azoxymethane/Dextran Sodium Sulfate Kusmardi K, Tamara R, Estuningtyas A, Tedjo A. International Journal of Applied Pharmaceutics.2019. CrossRef

- Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and its inhibitors in cancer: A minireview Mondal S, Adhikari N, Banerjee S, Amin SA , Jha T. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry.2020;194. CrossRef

- Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) as a Cancer Biomarker and MMP-9 Biosensors: Recent Advances Huang H. Sensors.2018;18(10). CrossRef

- Inhibition Of Carsinogenesis By Seed And Soybean Meal Extract In Colon Of Mice: Apoptosis And Dysplasia Arsianti AA , Amalia AW , Suid K, Elya B. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research.2017;10(4). CrossRef

- Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th edn) Albus U. Laboratory Animals.2012;46(3). CrossRef

- AOM/DSS Model of Colitis-Associated Cancer Parang B, Barrett CW , Williams CS . Gastrointestinal Physiology and Diseases.2016;1422.

- Murine Model for Colitis-Associated Cancer of the Colon Snider AJ , Bialkowska AB , Ghaleb AM , Yang VW , Obeid LM , Hannun YA . Mouse Models for Drug Discovery.2016;1438.

- Mouse Models for Application in Colorectal Cancer: Understanding the Pathogenesis and Relevance to the Human Condition Li C., Lau H.C.H., Zhang X., Yu J.. Biomedicines.2022;10(7). CrossRef

- Colitis-associated neoplasia: molecular basis and clinical translation Foersch S., Neurath M.F.. Cell Mol Life Sci CMLS.2014;71(18). CrossRef

- NF-κB pathway in colitis-associated cancers Viennois E., Chen F., Merlin D.. Transl Gastrointest Cancer.2013;2(1). CrossRef

- Aspirin inhibits MMP-9 mRNA expression and release via the PPARalpha/gamma and COX-2/mPGES-1-mediated pathways in macrophages derived from THP-1 cells Xue J., Hua Y.N., Xie M.L., Gu Z.L.. Biomed Pharmacother Biomedecine Pharmacother.2010;64(2). CrossRef

- Aspirin inhibits MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression and activity through PPARalpha/gamma and TIMP-1-mediated mechanisms in cultured mouse celiac macrophages Yiqin Y., Meilin X., Jie X., Keping Z.. Inflammation.2009;32(4). CrossRef

- Aspirin inhibits MMP-2 and MMP-9 expressions and activities through upregulation of PPAR alpha/gamma and TIMP gene expressions in ox-LDL-stimulated macrophages derived from human monocytes Hua Y., Xue J., Sun F., Zhu L., Xie M.. Pharmacology.2009;83(1). CrossRef

- Mechanisms of Colorectal Cancer Prevention by Aspirin-A Literature Review and Perspective on the Role of COX-Dependent and -Independent Pathways Sankaranarayanan R., Kumar D.R., Altinoz M.A., Bhat G.J.. Int J Mol Sci.2020;21(23). CrossRef

- Molecular targets of aspirin and cancer prevention Alfonso L., Ai G., Spitale R.C., Bhat G.J.. Br J Cancer.2014;111(1). CrossRef

- Aspirin inhibited the metastasis of colon cancer cells by inhibiting the expression of toll-like receptor 4 Ying J., Zhou H.Y., Liu P., You Q., Kuang F., Shen Y.N.. Cell Biosci.2018;8. CrossRef

- Aspirin promotes apoptosis in a murine model of colorectal cancer by mechanisms involving downregulation of IL-6-STAT3 signaling pathway Tian Y., Ye Y., Gao W., Chen H., Song T., Wang D.. Int J Colorectal Dis.2011;26(1). CrossRef

- Effects of chronic low‐dose aspirin treatment on tumor prevention in three mouse models of intestinal tumorigenesis Rohwer N, Kühl AA , Ostermann AI , Hartung NM , Schebb NH , Zopf D, McDonald FM , Weylandt K. Cancer Medicine.2020;9(7). CrossRef

- Aspirin inhibits prostaglandins to prevents colon tumor formation via down-regulating Wnt production Feng Y, Tao L, Wang G, Li Z, Yang M, He W, Zhong X, et al . European Journal of Pharmacology.2021;906. CrossRef

- Lunasin as a promising health-beneficial peptide Liu J., Jia S.-H., Kirberger M., Chen N.. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences.2014;18(14). CrossRef

- “Potential Health Benefits of Lunasin: A Multifaceted Soy‐Derived Bioactive Peptide” Lule VK , Garg S, Pophaly SD , Tomar SK . Journal of Food Science.2015;80(3). CrossRef

- Lunasin suppresses the migration and invasion of breast cancer cells by inhibiting matrix metalloproteinase-2/-9 via the FAK/Akt/ERK and NF-κB signaling pathways Jiang Q, Pan Y, Cheng Y, Li H, Liu D, Li H. Oncology Reports.2016;36(1). CrossRef

- Lunasin potentiates the effect of oxaliplatin preventing outgrowth of colon cancer metastasis, binds to α5β1 integrin and suppresses FAK/ERK/NF-κB signaling Dia VP , Gonzalez De Mejia E. Cancer Letters.2011;313(2). CrossRef

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright

© Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Biology , 2026

Author Details