The Inflammatory Bone Marrow Milieu: An Association Between CML Disease Activity, Systemic Inflammation, and Bone Turnover Independent of Vitamin D

Download

Abstract

Background: Metabolic bone disease is a recognized complication of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML), often linked to tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy or vitamin D deficiency. The ‘Inflammatory Bone Marrow Niche’ hypothesis suggests the leukemic microenvironment may independently disrupt bone metabolism.

Objective: To investigate whether markers of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) disease burden, such as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and markers of inflammation and iron homeostasis, including ferritin and interleukins, are associated with bone turnover markers parathyroid hormone (PTH) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) after controlling for vitamin D levels.

Patients and Methods: This retrospective cross-sectional study involved 90 adult patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who were receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy for at least 12 months at the Oncology Teaching Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq. Data were collected from January to September 2024 through patient records, measuring serum levels of vitamin D3, LDH, ferritin, PTH, and ALP. An inflammatory score was calculated using IL-6 and IL-1β, and multiple linear regression analyses were performed to identify independent associations.

Results: Multiple linear regression analysis identified lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (β=0.35, p=0.003) and the inflammatory composite score (β=0.28, p=0.012) as significant, independent predictors of elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP). Furthermore, ferritin levels were found to be a significant positive predictor of parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels (β = 0.31, p = 0.008). These associations remained statistically significant after adjusting for vitamin D3, which did not emerge as a significant predictor in either model.

Conclusion: This study provides a novel perspective, suggesting the leukemic microenvironment may be a key contributor to bone dysregulation in CML. The findings challenge traditional paradigms by indicating that bone health may also be influenced not only by calcium homeostasis and drug toxicity but also by disease-related molecular interactions. Monitoring inflammatory biomarkers could enhance risk stratification, facilitating comprehensive management of hematological and skeletal health.

1. Introduction

Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) exemplifies a successful paradigm in targeted cancer therapy, as treatments involving BCR-ABL1-specific tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been shown to facilitate long-term survival in most affected patients [1]. This therapeutic advancement has consequently redirected the clinical emphasis toward managing long-term treatment-associated complications and elucidating the intrinsic pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the disease. Notably, metabolic bone disease has emerged as a prominent and debilitating comorbidity, significantly impairing the quality of life in a considerable subset of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) [2].

The etiology of bone loss within this population is multifactorial and remains incompletely understood, posing a significant clinical challenge. Current explanatory frameworks for skeletal morbidity in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) predominantly focus on two primary mechanisms. Firstly, the iatrogenic effects of extended tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy are well established. Agents such as imatinib have been demonstrated to interfere with critical signaling pathways involved in bone remodeling. Specifically, they inhibit osteoblast differentiation and function through targeting platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) and c-FMS signaling pathways. Concurrently, they appear to augment osteoclast activity by influencing macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) signaling, resulting in a destabilization of the bone remodeling balance and consequent reduction in bone mineral density (BMD). [3, 4].

Second, a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency has been consistently reported in cohorts with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), which can independently induce secondary hyperparathyroidism, enhance bone resorption, and lead to mineralization disturbances [5]. While these factors are undoubtedly significant, they provide only a partial perspective. Clinical observations demonstrate that bone loss frequently occurs before the initiation of TKI therapy or in patients with sufficient vitamin D levels, strongly suggesting the influence of intrinsic, leukemia-driven pathogenic mechanisms that operate independently of therapeutic interventions or nutritional status [2]. This gap in understanding directs attention towards the bone marrow (BM) microenvironment, or “niche,” which is increasingly recognized not merely as a passive scaffold but as a dynamic and integral participant in both normal hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis.

The physiological BM niche is a dynamic microenvironment that regulates normal hematopoiesis. In CML, this homeostasis is subverted by leukemic clones, which actively remodel the niche into a self-sustaining, pro-inflammatory sanctuary [6-8]. This remodeled microenvironment supports the survival of leukemic cells, facilitates their proliferation, and confers resistance to therapeutic interventions [9]. A state of chronic inflammation characterizes this remodeled leukemic niche. Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) cells produce a wide array of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β), thereby stimulating systemic acute-phase responses [10]. This pro-inflammatory state is further substantiated by elevated levels of biomarkers, such as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), which indicates a high tumor burden and increased cellular turnover, and ferritin, an acute-phase reactant whose levels are affected by both inflammatory processes and disruptions in iron homeostasis (hyperferritinemia).[11, 12].

We hereby propose the “Inflammatory Bone Marrow Niche” hypothesis to elucidate the intrinsic mechanism underlying bone dysregulation in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). This hypothesis suggests that the CML clone actively modulates a pro-inflammatory microenvironment within the bone marrow, which subsequently disrupts normal bone metabolism through the dysregulation of osteoblastic and osteoclastic activities. The inflammatory milieu, characterized by elevated cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), functions as a potent inducer of osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption via the RANKL/RANK/OPG signaling pathway [13, 14]. Concurrently, this environment has the potential to inhibit osteoblastogenesis and induce apoptosis of osteogenic cells, thereby impairing the process of new bone formation [15].

This dual assault results in a significant disruption of the bone remodeling process. Furthermore, it is hypothesized that this inflammation-induced dysregulation may operate independently of the traditional calcium-vitamin D-PTH axis. Specifically, the systemic inflammatory state, as indicated by hyperferritinemia, could directly influence parathyroid gland activity or modify its calcium set-point, thereby causing elevated PTH levels irrespective of vitamin D levels a phenomenon also observed in other chronic inflammatory diseases [16, 17].

Therefore, this cross-sectional study aims to evaluate the foundational principles of the proposed hypothesis empirically. Specifically, the study investigates whether distinct, quantifiable markers of the hypothesized inflammatory niche, LDH (a marker of disease activity), ferritin (a marker of inflammation and iron storage), and a composite score derived from pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and IL-1β), are independently associated with key systemic bone turnover markers such as alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and parathyroid hormone (PTH).

Crucially, this analysis is conducted with careful adjustment for the confounding effects of vitamin D status. By delineating these independent associations, the study aims to provide robust evidence for a paradigm shift in understanding skeletal health in CML. This shift extends the focus beyond solely drug toxicity and nutrient deficiency to encompass the direct, pathogenic contributions of the leukemic inflammatory microenvironment.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This retrospective, single-center, cross-sectional study was carried out at the Oncology Teaching Hospital in Baghdad, Iraq. The study aimed to explore the relationship between markers of CML disease activity, inflammation, and bone turnover, while considering vitamin D status. Analysis was conducted on anonymized laboratory data from 90 adult patients with CML who had been on TKI therapy for at least 12 months, collected between January 2024 and September 2024. The institutional review board approved the study and waived the requirement for informed consent, as it utilized pre-existing, anonymized data.

2.2. Study Setting and Population

The cohort comprised adults aged 18 years and older with a confirmed diagnosis of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), established by an oncologist in accordance with World Health Organization (WHO) criteria. Participants had also undergone comprehensive biochemical testing.

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria: Selected patients were required to meet all of the following criteria

Being adults aged 18 years or older; having a confirmed diagnosis of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) according to standard World Health Organization (WHO) criteria; having received continuous TKI therapy for at least 12 months prior to data collection and having comprehensive biochemical profiles during the study period, including assessments of Parathyroid Hormone (PTH), Vitamin D3 levels, serum creatinine, Alkaline Phosphatase, serum ferritin, total serum calcium, and proinflammatory cytokines.

We intentionally selected a therapy duration involving TKI of at least 12 months, given that the initial months of TKI treatment may induce significant biochemical and hematological fluctuations. Establishing a 12-month baseline ensures greater stability in patient conditions, thereby facilitating a more accurate assessment of the long-term effects of the disease and therapeutic intervention.

Due to the retrospective design of this study and its primary focus on investigating intrinsic inflammatory pathways, it was not possible to perform comprehensive statistical adjustments for the specific TKI type or molecular response in the main multivariate models. This limitation arose from incomplete data on molecular response and the risk of model overfitting, considering the sample size and number of covariates.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Patients were excluded from the analysis based on specific criteria, including the presence of known pre-existing metabolic bone diseases such as primary hyperparathyroidism, Paget’s disease of the bone, and osteogenesis imperfecta. Additional exclusions encompassed a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease (CKD Stage 4 or 5), characterized by an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of less than 30 mL/min/1.73 m², before the diagnosis of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Patients with a history of malabsorption syndromes, such as celiac disease and inflammatory bowel disease, or those who had undergone bariatric surgery conditions known to impact vitamin D and calcium metabolism independently were also excluded. Additional exclusions included current pregnancy or lactation, as well as instances of incomplete or missing laboratory data critical to key variables of interest.

Additionally, patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis of any other active malignancy (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer), chronic inflammatory or autoimmune disorders (such as rheumatoid arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease), or active systemic infections, as these conditions could independently influence systemic inflammatory and bone turnover markers.

2. 3. Data Collection and Laboratory Methods

Venous blood specimens (approximately 5 mL) were collected from each participant following an overnight fast of 8 to 12 hours. To minimize the immediate effects of TKI administration on laboratory parameters, all samples were drawn just before the patient’s daily scheduled TKI dose, ensuring measurement at trough concentration. Blood was collected into plain vacuum tubes designated for serum separation. The samples were allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 minutes, then centrifuged at 3,500 rpm for 10 minutes using a Hettich EBA 200 centrifuge. The supernatant serum was subsequently aliquoted and either analyzed immediately or stored at -20°C for batch testing within one week.

All biochemical determinations were conducted at the central laboratory of the Oncology Teaching Hospital employing standardized and validated protocols.

The particular analytical techniques and instruments employed for each parameter are detailed as follows:

1. Parathyroid Hormone (PTH): Serum intact PTH was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The commercially available Monobind PTH ELISA kit (Lake Forest, USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the absorbance was read on a BioTek ELx800 microplate reader [18].

2. Vitamin D3 (25-Hydroxyvitamin D): Total 25-Hydroxyvitamin D levels were determined using a competitive ELISA. The DiaSource 25-OH Vitamin D Total ELISA kit (Belgium) was employed, with results quantified using the same BioTek ELx800 microplate reader [19].

3. Serum creatinine: The measurement was conducted using the modified Jaffe reaction, a kinetic colorimetric assay, without deproteinization. The procedure was performed on a Mindray BS-200 Chemistry Analyzer [20].

4. Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP): ALP activity was quantified using the AMP buffer method, while Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) levels were determined via the DGKC method. Both assays were conducted on the Mindray BS-200 Chemistry Analyzer [21].

5. Serum ferritin: The measurement was conducted employing a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique utilizing a Ferritin ELISA kit (Diagnostics Automation, USA). The absorbance was read using a BioTek ELx800 microplate reader [22].

6. Total serum calcium: it was determined by a colorimetric assay (o-cresolphthalein complexone method). All tests were run on the Mindray BS-200 Chemistry Analyzer. Corrected calcium was calculated using the standard formula: Corrected Calcium (mg/dL) = measured total Ca + 0.8 * (4.0 - patient albumin g/dL) [23].

7. Pro-inflammatory Cytokines: Serum levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) were quantified using high-sensitivity ELISA kits (e.g., Diaclone SAS, France) on the BioTek ELx800 microplate reader. To create a holistic measure of inflammatory burden, an Inflammatory Composite Score was calculated.

The raw IL-6 and IL-1β concentrations were converted to Z-scores, and the composite score for each patient was derived as the sum of these Z-scores [24, 25].

Internal quality control was performed daily using commercial control sera at two levels (normal and pathological). The laboratory also participates in an external quality assurance scheme.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the medical faculty of Al-Fallujah University (Approval Number: [6 in 1-10-2025]), ensuring adherence to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Given the retrospective nature of the study using anonymized data, the requirement for individual informed consent was waived by the approving IRB to protect patient confidentiality.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Normality of continuous variables was assessed via the Shapiro-Wilk test. Descriptive statistics included means and standard deviations (SD) for normally distributed data, and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) for non-normal data. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. The primary analyses consisted of two multiple linear regression models designed to test the study’s central hypothesis. These models evaluated the independent associations between disease activity, inflammatory markers, and bone turnover markers, with adjustments for vitamin D status.

Model 1: ALP = β₀ + β₁ (Vitamin D3) + β₂ (LDH) + β₃ (Ferritin) + β₄ (Inflammatory Composite Score) Model 2: PTH = β₀ + β₁ (Vitamin D3) + β₂ (LDH) + β₃ (Ferritin) + β₄ (Inflammatory Composite Score)

The fundamental assumptions of linear regression linearity, homoscedasticity, and the normality of residuals were rigorously evaluated through graphical diagnostics and subsequently confirmed. Multicollinearity among the predictor variables was quantified using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), with a threshold of less than 5 established as acceptable, indicating the absence of significant multicollinearity.

Due to the high correlation observed between the Inflammatory Composite Score and LDH (r = 0.85) and Ferritin (r = 0.78) in bivariate analysis, which suggests the presence of multicollinearity despite acceptable VIF values, further regression analyses were conducted. These additional models, which are more parsimonious and focus solely on LDH and Ferritin clinically accessible markers were implemented to evaluate the robustness of the associations in the absence of the inflammatory score.

Furthermore, bivariate correlations among key study variables were evaluated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient for data that met normality assumptions.

A significance level of p < 0.05 (two-tailed) was applied for all statistical analyses [26].

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Cohort

A total of 90 adult patients with a confirmed diagnosis of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) were included in the final analysis. The study population had a mean age of 54.2 ± 11.8 years, with ages ranging from 28 to 78 years, reflecting a cohort primarily comprising middle-aged to older adults.

The cohort exhibited substantial heterogeneity across various parameters, including disease activity, inflammatory responses, and metabolic profiles. Notably, bone turnover markers demonstrated significant variability: Parathyroid Hormone (PTH) levels ranged from 11.9 to 446.3 pg/mL, with a median of 33.8 pg/ mL and an interquartile range (IQR) of 24.6 to 44.7 pg/ mL. Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) levels also showed considerable variation, spanning from 66.5 to 122.3 U/L, with a median of 93.2 U/L and an IQR of 84.6 to 99.0 U/L. Furthermore, vitamin D3 concentrations exhibited high dispersion, with a mean value of 32.6 ± 17.5 ng/mL, reflecting a substantial prevalence of insufficiency and deficiency within the cohort.

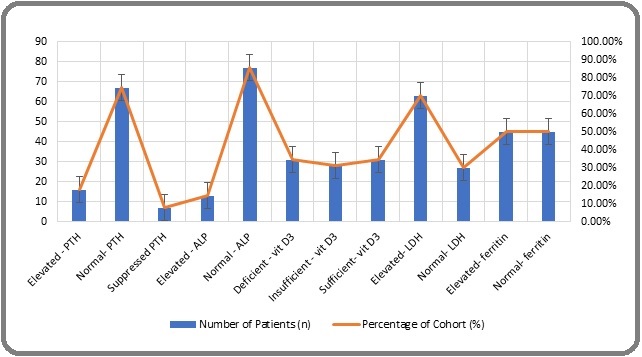

Markers of disease activity and inflammation demonstrated considerable variability. Levels of Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) and Ferritin were heterogeneous, indicating differences in tumor burden and acute-phase response among patients. Additionally, pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and IL-1β, showed a broad range of concentrations, with IL-6 levels ranging from 5.1 to 25.6 pg/mL and IL-1β from 0.6 to 3.5 pg/mL. The Inflammatory Composite Score, a derived metric combining cytokine measurements, effectively encapsulated the spectrum of inflammatory states observed (mean: 0.0 ± 1.0; range: -2.1 to 2.9). This heterogeneity highlights the diverse clinical and inflammatory profiles present within the patient cohort. See Table 1. Figure 1.

| Variable | Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | Min - Max | Reference Range |

| Demographic | ||||

| Age (Years) | 54.2 ± 11.8 | 55.0 (46.0 - 62.0) | 28.0 - 78.0 | - |

| Bone Turnover Markers | ||||

| PTH (pg/mL) | 39.1 ± 52.5 | 33.8 (24.6 - 44.7) | 11.9 - 446.3 | 15 - 65 |

| ALP (U/L) | 92.5 ± 14.8 | 93.2 (84.6 - 99.0) | 66.5 - 122.3 | 40 - 129 |

| Predictor Variables | ||||

| Vitamin D3 (ng/mL) | 32.6 ± 17.5 | 28.6 (18.5 - 39.2) | 10.2 - 74.6 | >30 (Sufficient) |

| LDH (U/L) | 266.7 ± 85.1 | 278.6 (246.2 - 322.0) | 120.3 - 572.5 | 125 - 220 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 404.3 ± 592.6 | 367.5 (298.5 - 411.2) | 22.3 - 2743.2 | 30 - 400 |

| Inflammatory Markers | ||||

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 16.8 ± 7.2 | 16.5 (11.2 - 21.8) | 5.1 - 25.6 | - |

| IL-1β (pg/mL) | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 2.4 (1.7 - 3.1) | 0.6 - 3.5 | - |

| Inflammatory Composite Score (Z-score) | 0.0 ± 1.0 | -0.1 (-0.6 - 0.6) | -5 | - |

| Other Parameters | ||||

| Corrected Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.3 ± 0.6 | 9.4 (9.1 - 9.6) | 7.8 - 10.3 | 8.6 - 10.3 |

| Serum Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.79 ± 0.16 | 0.83 (0.66 - 0.93) | 0.50 - 1.20 | 0.7 - 1.3 |

| Duration of TKI (Months) | 45.2 ± 28.1 | 42.0 (24.0 - 60.0) | 12 - 120 |

*Data are presented as Mean ± Standard Deviation (SD), Median (Interquartile Range, IQR), and Minimum-Maximum range. Reference ranges provided are based on the laboratory's standardized values. PTH, Parathyroid Hormone; ALP, Alkaline Phosphatase; LDH, Lactate Dehydrogenase; IL-6, Interleukin-6; IL-1β, Interleukin-1β.TKI, tyrosine kinase therapy. The cohort was heterogeneous in terms of TKI therapy, comprising patients on imatinib (n=63, 70.0%), nilotinib (n=18, 20.0%), and dasatinib (n=9, 10.0%).

Figure 1. Prevalence of Abnormal Bone and Inflammatory Parameters in the CML Cohort (n=90).

3.2. Correlations between Study Variables

Bivariate correlation analysis employing Pearson’s correlation coefficient identified several significant associations among the variables. The findings indicated that the disease activity marker, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), exhibited a significant positive correlation with the bone turnover marker alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (r = 0.372, p < 0.001). Additionally, the inflammatory composite score was positively correlated with ALP (r = 0.324, p = 0.002). Regarding parathyroid hormone (PTH), ferritin demonstrated a significant positive correlation (r = 0.301, p = 0.004).

Vitamin D3 concentrations did not exhibit significant correlations with either parathyroid hormone (PTH) (r = -0.125, p = 0.240) or alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (r = -0.064, p = 0.548) in the bivariate analysis. The inflammatory composite score demonstrated strong correlations with its constituent surrogate markers, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (r = 0.85, p < 0.001) and ferritin (r = 0.78, p < 0.001), thereby confirming its validity as a composite inflammatory index Table 2.

| Variable | PTH | ALP | Vitamin D3 | LDH | Ferritin | Inflammatory Score |

| PTH | 1 | - | - | - | - | |

| ALP | 0.104 | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Vitamin D3 | -0.125 | -0.064 | 1 | - | - | - |

| LDH | 0.158 | 0.372* | 0.041 | 1 | - | - |

| Ferritin | 0.301* | 0.185 | -0.088 | 0.422* | 1 | - |

| Inflammatory Score | 0.192 | 0.324* | -0.032 | 0.850* | 0.780* | 1 |

*Correlation coefficients (r-values) are derived from Pearson's correlation analysis. * Indicates a statistically significant correlation with a p-value< 0.05. PTH, Parathyroid Hormone; ALP, Alkaline Phosphatase; LDH, Lactate Dehydrogenase.

Multiple Linear Regression Analysis for Predictors of Bone Turnover: (with the impact of inflammatory score) To assess the independent associations of disease activity and inflammation with bone turnover markers while accounting for vitamin D status, two multiple linear regression models were constructed. The assumptions of linearity, homoscedasticity, and normality of residuals were verified and found to be satisfied. Additionally, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values for all predictors were below 3, indicating the absence of significant multicollinearity.

Table 3 shows the results of the regression analyses.

| Dependent Variable | Predictor Variable | Unstandardized Beta (B) | Standard Error | Standardized Beta (β) | t-value | p-value |

| Model 1: ALP | (Constant) | 70.15 | 8.92 | 7.86 | <0.001 | |

| Vitamin D3 | -0.06 | 0.08 | -0.07 | -0.76 | 0.45 | |

| LDH | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.35 | 3.08 | 0.003 | |

| Ferritin | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.12 | 1.1 | 0.274 | |

| Inflammatory Score | 4.15 | 1.61 | 0.28 | 2.58 | 0.012 | |

| Model 2: PTH | (Constant) | 25.11 | 18.21 | - | 1.38 | 0.172 |

| Vitamin D3 | -0.33 | 0.3 | -0.11 | -1.09 | 0.28 | |

| LDH | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.1 | 0.87 | 0.385 | |

| Ferritin | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.31 | 2.73 | 0.008 | |

| Inflammatory Score | 3.82 | 3.29 | 0.12 | 1.16 | 0.249 |

Two separate multiple linear regression models were constructed to identify independent predictors of bone turnover markers. Model 1: Dependent variable = Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP). Model 2: Dependent variable = Parathyroid Hormone (PTH). Bolded values indicate a statistically significant predictor (p < 0.05). B, unstandardized beta coefficient; β, standardized beta coefficient.

Model 1, with alkaline phosphatase (ALP) as the dependent variable, demonstrated statistical significance (F(4, 85) = 7.12, p < 0.001), with an adjusted R-squared of 0.22. Within this model, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (β = 0.35, p = 0.003) and the inflammatory composite score (β = 0.28, p = 0.012) emerged as significant positive predictors of ALP levels. These findings indicate that greater disease activity and heightened inflammatory states are independently associated with increased bone turnover, as evidenced by ALP levels. Conversely, vitamin D3 did not serve as a significant predictor in this model (β = -0.07, p = 0.45).

Model 2, with parathyroid hormone (PTH) as the dependent variable, was also statistically significant (F (4, 85) = 4.08, p = 0.004; Adjusted R² = 0.13). Ferritin emerged as an important positive predictor of PTH levels (β = 0.31, p = 0.008), independently of vitamin D3, which remained non-significant (β = -0.11, p = 0.28). Neither lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) nor the inflammatory composite score significantly predicted PTH in this multivariate model.

To reduce the impact of high collinearity among predictors, additional multiple linear regression analyses were performed, excluding the inflammatory composite score. In the model predicting alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (F (3, 86) = 8.94, p < 0.001; Adjusted R² = 0.21), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) remained a significant positive predictor (β = 0.40, p < 0.001), while ferritin did not reach statistical significance (β = 0.10, p = 0.30). Conversely, in the model predicting parathyroid hormone (PTH) (F (3, 86) = 5.12, p = 0.003; Adjusted R² = 0.12), ferritin continued to be a significant positive predictor (β = 0.33, p = 0.003), whereas LDH was not significantly linked (β = 0.08, p = 0.45). Vitamin D3 was not a significant predictor in either supplementary model. These results confirm the strong, independent links of LDH with ALP and ferritin with PTH, regardless of the inflammatory score, which was excluded to address multicollinearity.

Given the substantial correlation (r = 0.85) between the Inflammatory Composite Score and LDH, indicating that these markers reflect a closely related pathogenic construct, we employed parsimonious regression models excluding the inflammatory score to address multicollinearity and improve clinical relevance. In the model predicting ALP, LDH remained a significant positive predictor (β = 0.40, p < 0.001). Conversely, in the model predicting PTH, ferritin emerged as an important positive predictor (β = 0.33, p = 0.003). These findings provide robust evidence that a unified ‘disease burden/ inflammation’ axis, measurable through LDH and ferritin, is independently associated with bone turnover markers. Table 4.

| Dependent Variable | Predictor Variable | Unstandardized Beta (B) | Standard Error | Standardized Beta (β) | t-value | p-value |

| Model 1: ALP | (Constant) | 72.45 | 7.92 | - | 9.15 | <0.001 |

| Vitamin D3 | -0.05 | 0.08 | -0.06 | -0.66 | 0.509 | |

| LDH | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.4 | 4.41 | <0.001 | |

| Ferritin | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.1 | 1.04 | 0.3 | |

| Model 2: PTH | (Constant) | 26.18 | 17.21 | - | 1.52 | 0.132 |

| Vitamin D3 | -0.31 | 0.29 | -0.1 | -1.05 | 0.295 | |

| LDH | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.76 | 0.45 | |

| Ferritin | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.33 | 3.08 | 0.003 |

Two separate multiple linear regression models were developed to identify independent predictors of bone turnover markers, excluding the Inflammatory Composite Score to reduce multicollinearity. Model 1: Dependent variable = Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP). Model 2: Dependent variable = Parathyroid Hormone (PTH). Bolded values indicate a statistically significant predictor (p < 0.05). B, unstandardized beta coefficient; β, standardized beta coefficient.

4. Discussion

This investigation seeks to elucidate a critical yet frequently neglected aspect in the management of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML): the prevalence of metabolic bone disease. While the deleterious impact of prolonged tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy on skeletal integrity and the commonality of vitamin D deficiency among these patients are well-documented, our findings suggest an additional, non-exclusive factor that may be involved [27-29].

We hypothesize that the leukemic bone marrow niche, characterized by heightened disease activity and a pro-inflammatory environment, may serve as a potential contributor to dysregulation in bone metabolism. Our findings provide support for this “Inflammatory Bone Marrow Niche” hypothesis, demonstrating that markers indicative of disease burden and systemic inflammation are independently associated with abnormal bone turnover, even after adjusting for vitamin D levels.

The primary objective of this cross-sectional study was to investigate the associations among markers of CML disease activity, specifically lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), indicators of inflammation and iron homeostasis, including ferritin, IL-6, and IL-1β, as well as key bone turnover markers such as parathyroid hormone (PTH) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP).

Our findings are consistent with the primary hypothesis. The multiple regression analyses demonstrated that lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), a recognized biomarker for tumor burden and cellular turnover in hematological malignancies, serves as a significant, independent positive predictor of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels (β = 0.35, p = 0.003). This suggests that the metabolic activity and cellular turnover of the chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) clone may be implicated in increased bone remodeling. Furthermore, the inflammatory composite score, derived from the pro-osteoclastogenic cytokines IL-6 and IL-1β, was identified as a significant independent predictor of ALP (β = 0.28, p = 0.012). This result highlights the potential role of the inflammatory microenvironment within the bone marrow in the context of osteoclast activation and bone resorption processes that are pivotal to the pathogenesis of leukemia-associated bone disease [30, 31].

Equally noteworthy was the finding that ferritin, an acute-phase reactant and a marker of iron storage and inflammation, emerged as a significant independent predictor of PTH levels (β = 0.31, p = 0.008). This association persisted after adjusting for vitamin D3, which did not prove to be a significant predictor in either model. This dissociation of parathyroid hormone (PTH) from the conventional calcium-vitamin D pathway represents a novel finding within the context of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). It implies a potential link whereby the inflammatory state, as evidenced by hyperferritinemia, may influence PTH secretion or modulate its regulatory mechanisms.

Our findings enable us to propose a coherent pathogenic sequence linking systemic inflammation to bone dysregulation in CML, operating independently of the calcium-vitamin D axis. This model starts with the chronic inflammatory state characteristic of active CML, which disrupts iron homeostasis and manifests as hyperferritinemia [32, 33]. We hypothesize that this inflammatory environment, marked by elevated ferritin, directly affects parathyroid gland function. This is supported by evidence from other chronic diseases where inflammation influences PTH secretion independently of calcium and vitamin D [34, 35]. Providing a plausible explanation for our observed ferritin-PTH association, the resulting increase in PTH then directly drives increased bone turnover, completing the pathway: Systemic Inflammation → Hyperferritinemia → PTH Elevation→ Increased Bone Turnover. This model places the inflammatory bone marrow niche at the center of a systemic endocrine disturbance with direct effects on the skeleton.

This provides a plausible explanation for the observed association between elevated ferritin levels and increased parathyroid hormone (PTH). Consequently, this aberrant elevation in PTH could contribute to heightened bone turnover. Based on these findings, we propose a potential sequence of pathogenic events in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML): systemic inflammation may lead to hyperferritinemia, which could subsequently be associated with PTH elevation, potentially culminating in increased bone turnover.

The absence of a significant link between vitamin D3 and bone turnover markers in our multivariate analysis is a notable finding. This challenges the common perspective that vitamin D deficiency is the main cause of bone problems in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), suggesting a need to reevaluate the underlying biological mechanisms. Although vitamin D insufficiency is common and plays a role, our results suggest that the disturbances associated with the leukemic environment especially high disease activity and inflammation may have a stronger association with bone turnover in this specific patient group. This view aligns with emerging concepts in onco-metabolism, which regard the tumor microenvironment as an active endocrine and paracrine organ capable of inducing systemic metabolic disturbances [36-38].

When considered in the context of existing scholarly literature, our findings both support and expand on previous research. Numerous studies have documented elevated markers of bone resorption and a higher risk of osteoporosis among patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), often attributing these outcomes solely to the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) [39, 40].

However, our study design, by focusing on the disease’s intrinsic biology, reveals associations for a pathway that appears to function independently of TKI pharmacology. The involvement of inflammation in cancer-associated bone pathology is well-documented in solid tumors such as breast cancer and multiple myeloma, wherein cytokines, including IL-6 and RANKL, serve as critical mediators of osteolytic lesions [41, 42].

Our study extends this concept to CML, demonstrating an association between a corresponding pro-inflammatory milieu assessed via our composite score is associated with systemic bone turnover. Additionally, recent investigations have indicated that CML stem cells can alter the bone marrow endosteal niche [6, 43, 44]. In contrast, Our research offers a plausible mechanistic link systemic inflammation through which this altered niche may be associated with disrupted skeletal homeostasis. The robust correlation observed between our inflammatory composite score and its constituent markers, LDH and Ferritin, substantiates its utility as a comprehensive indicator of inflammatory burden. This approach surpasses reliance on a single cytokine, as it better encapsulates the complex and multifaceted nature of the inflammatory response in oncological contexts [7, 45, 46].

Our findings demonstrate a significant correlation between markers of CML disease activity and systemic inflammation, suggesting that these parameters reflect convergent aspects of the ‘Inflamed Leukemic Niche.’ The notable association between LDH and the inflammatory score indicates that an actively proliferating leukemic clone and a pro-inflammatory microenvironment are mutually reinforcing components of a unified pathogenic process. Furthermore, simplified models that identify LDH and ferritin as key predictors effectively capture this overarching axis of ‘disease burden and inflammation.’ This framework offers a clinically practical means to evaluate the influence of the leukemic microenvironment on skeletal health.

This study’s principal limitation lies in its cross- sectional design, which precludes causal inferences. Additionally, the investigation being confined to a single center limits the generalizability of the results. The absence of comprehensive statistical adjustments for specific TKI types or molecular responses further underscores this constraint. Accordingly, the reported associations necessitate validation through multicenter, longitudinal studies to establish temporal relationships and to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms. Moreover, although ALP and PTH are user-friendly and valuable, future research should incorporate more specific biomarkers such as CTX and P1NP to validate the findings.

In conclusion, metabolic bone disease remains a significant yet not fully understood complication of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML), often associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy and vitamin D deficiency. This study explores this issue by proposing and examining a new pathogenic pathway called the ‘Inflammatory Bone Marrow Niche.’

This study establishes that a unified disease burden/ inflammation axis, measurable through the accessible biomarkers lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and ferritin, is independently associated with increased bone turnover in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). This finding challenges the conventional paradigm by emphasizing the direct role of the leukemic inflammatory microenvironment in bone dysregulation, operating independently of vitamin D status. The results demonstrate that intrinsic disease activity, as indicated by LDH levels, and systemic inflammation, as reflected by ferritin concentrations and a cytokine-based composite score, are independently correlated with elevated markers of bone turnover, namely alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and parathyroid hormone (PTH), even after adjusting for vitamin D levels. These insights highlight the critical contribution of inflammation to skeletal alterations in CML and suggest potential therapeutic targets within the inflammatory pathways to mitigate bone dysregulation associated with the disease.

This study presents a novel and significant perspective, suggesting that the leukemic microenvironment directly contributes to bone dysregulation. By identifying these new associations, our research redefines the existing paradigm, indicating that bone health in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is not solely governed by calcium homeostasis or the effects of pharmacological toxicity.

These findings indicate that therapeutic interventions capable of attaining profound molecular responses may offer a dual advantage: effectively controlling leukemia while also reducing associated inflammatory osteoarticular complications. The monitoring of accessible inflammatory biomarkers could facilitate the identification of patients at increased risk, thereby enabling a more comprehensive approach to managing chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) that addresses both hematological parameters and skeletal health.

Future research should employ longitudinal, multi-center studies with advanced imaging and histomorphometry to establish causality, validate findings across diverse populations, and investigate molecular interactions, aiming to identify therapeutic targets that maintain skeletal health in leukemia.

Author Contributions

Design and development: Mohammed Amer Fayyadh, Waleed Khalid Ahmed, Youssef Shakuri. Gathering and organizing data: Wissam Mahmood Mohammed Atiyah Al-Mohammadi. Data analysis/interpretation: Azal Hamoody Jumaa, Mohammed Amer Fayyadh, Waleed Khalid Ahmed. Article composition: Waleed Khalid Ahmed. Critique the essay for significant ideas: Mohammed Amer Fayyadh. Statistical analysis expertise: Wissam Mahmood Mohammed Atiyah Al-Mohammadi. Ultimate article endorsement and guarantee: Youssef Shakuri , Mohammed Amer Fayyadh.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the nursing and administrative staff of the Oncology Teaching Hospital in Baghdad, Iraq, for their invaluable assistance with data collection and patient care. We deeply appreciate the dedicated team at the central laboratory for their meticulous work in sample processing and biochemical analysis, which greatly contributed to this study. Finally, we are profoundly grateful to the patients themselves, whose willingness to participate made this research possible.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was conducted without any direct financial support from public, commercial, or nonprofit funding bodies. The authors funded the research independently.

Conflicts of interest

The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest to report.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The authors state that this work does not utilize any generative AI or AI-assisted tools.

Abbreviations

CML, Chronic Myeloid Leukemia; ALP, Alkaline Phosphatase; BUN, Blood Urea Nitrogen; CKD, Chronic Kidney Disease; eGFR, estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate; ELISA, Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay; IL-1β, Interleukin-1 Beta; IL-6, Interleukin-6; IQR, Interquartile Range; IRB, Institutional Review Board; LDH, Lactate Dehydrogenase; PTH, Parathyroid Hormone; SD, Standard Deviation; TIBC, Total Iron-Binding Capacity; TKI, Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor

References

- Long-Term Outcomes of Imatinib Real-Life Treatment for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia- a 20-Year Review Szczepanek E, Chukwu O, Kaminska M, Wysoglad H, Cenda A, Waclaw J, Zawada M, Jakobczyk M, Sacha T. Blood.2020;136. CrossRef

- Bone health in patients of chronic myeloid leukemia on imatinib therapy Yadav A, Yadav M. Sch J Appl Med Sci.2021;9(3):390-392. CrossRef

- Impact of tyrosine kinase inhibitors and bone morphogenetic proteins on persistent leukemic stem cell dormancy in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia patients at remission: Université Claude Bernard-Lyon I Arizkane K. 2022.

- Bone Mineral Density, C-Terminal Telopeptide of Type I Collagen, and Osteocalcin as Monitoring Parameters of Bone Remodeling in CML Patients Undergoing Imatinib Therapy: A Basic Science and Clinical Review Indarwulan N, Savitri M, Ashariati A, Bintoro SUY , Diansyah MN , Amrita PNA , Romadhon PZ . Diseases (Basel, Switzerland).2024;12(11). CrossRef

- Vitamin D Deficiency, Osteoporosis and Effect on Autoimmune Diseases and Hematopoiesis: A Review De Martinis M, Allegra A, Sirufo MM , Tonacci A, Pioggia G, Raggiunti M, Ginaldi L, Gangemi S. International Journal of Molecular Sciences.2021;22(16). CrossRef

- Bone marrow niches in haematological malignancies Méndez-Ferrer S, Bonnet D, Steensma DP , Hasserjian RP , Ghobrial IM , Gribben JG , Andreeff M, Krause DS . Nature Reviews. Cancer.2020;20(5). CrossRef

- NFĸB and its inhibitors in preeclampsia: mechanisms and potential interventions Jasim MH , Mukhlif BAM , Uthirapathy S, Zaidan NK , Ballal S, Singh A, Sharma GC , Devi A, Mohammed WM , Mekkey SM . Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology.2025;398(10). CrossRef

- Characterization of the bone marrow niche in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia identifies CXCL14 as a new therapeutic option Dolinska M, Cai H, Månsson A, Shen J, Xiao P, Bouderlique T, Li X, et al . Blood.2023;142(1). CrossRef

- Wnt Signaling in Leukemia and Its Bone Marrow Microenvironment Ruan Y, Kim HN , Ogana H, Kim YM . International Journal of Molecular Sciences.2020;21(17). CrossRef

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells impair osteoblastogenesis and promote osteoclastogenesis: role of TNFα, IL-6 and IL-11 cytokines Giannoni P, Marini C, Cutrona G, Matis S, Capra MC , Puglisi F, Luzzi P, et al . Haematologica.2021;106(10). CrossRef

- IFNγ directly counteracts imatinib-induced apoptosis of primary human CD34+ CML stem/progenitor cells potentially through the upregulation of multiple key survival factors Ujvari D, Malyukova A, Zovko A, Yektaei-Karin E, Madapura HS , Keszei M, Nagy N, et al . Oncoimmunology.2022;11(1). CrossRef

- Hyperferritinemia-A Clinical Overview Sandnes M, Ulvik RJ , Vorland M, Reikvam H. Journal of Clinical Medicine.2021;10(9). CrossRef

- The JAK1/STAT3/SOCS3 axis in bone development, physiology, and pathology Sims NA . Exp Mol Med.2020;52:1185–1197. CrossRef

- The effect of cytokines on osteoblasts and osteoclasts in bone remodeling in osteoporosis: a review Xu J, Yu L, Liu F, Wan L, Deng Z. Frontiers in Immunology.2023;14. CrossRef

- Osteoimmunology: The Crosstalk between T Cells, B Cells, and Osteoclasts in Rheumatoid Arthritis Yang M, Zhu L. International Journal of Molecular Sciences.2024;25(5). CrossRef

- Body weight and its influence on hepcidin levels in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies Ndevahoma F, Mukesi M, Dludla PV , Nkambule BB , Nepolo EP , Nyambuya TM . Heliyon.2021;7(3). CrossRef

- Molecular Mechanisms of Parathyroid Disorders in Chronic Kidney Disease Hassan A, Khalaily N, Kilav-Levin R, Nechama M, Volovelsky O, Silver J, Naveh-Many T. Metabolites.2022;12(2). CrossRef

- Asymptomatic elevated parathyroid hormone level due to immunoassay interference Zanchetta MB , Giacoia E, Jerkovich F, Fradinger E. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA.2021;32(10). CrossRef

- Comparison between liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and immunoassay methods for measurement of plasma 25 (OH) vitamin D Kader S, Akdag T, Ecer B, Abusoglu S, Unlu A. Turkish Journal of Biochemistry. 2022;47(6):710-8.. CrossRef

- Evaluation of Enzymatic Sarcosine Oxidase Method and Comparison with Modified Kinetic Jaffe’s Reaction Analytical Method for Quantitative Analysis of Creatinine: JKUAT-COHES Kula SB . 2022.

- Low-Cost Point-of-Care Monitoring of ALT and AST Is Promising for Faster Decision Making and Diagnosis of Acute Liver Injury Chinnappan R, Mir TA , Alsalameh S, Makhzoum T, Alzhrani A, Al-Kattan K, Yaqinuddin A. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland).2023;13(18). CrossRef

- Comparative Analysis of Serum and Saliva Iron, Ferritin, and TIBC in Women with Iron Deficiency Anemia: Highlighting Saliva's Screening Potential Farrokhnia T, Shoorgashti R, Sadeghian M, Hasanzade S, Lesan S, Hedayati M. Middle East Journal of Rehabilitation and Health Studies.;11(4).

- Effect Of Blood Collection Tubes On Estimation Of Sodium, Potassium, Calcium And Lithium: Our Experience Saharia G, Mangaraj M. .

- Anti-inflammatory effect of interleukin-6 highly enriched in secretome of two clinically relevant sources of mesenchymal stromal cells Dedier M, Magne B, Nivet M, Banzet S, Trouillas M. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology.2023;11. CrossRef

- Associations of Blood Absolute Neutrophil Count and Cytokines With Cognitive Function in Dementia-Free Participants: A Population-Based Cohort Study Fa W, Liang X, Liu K, Wang N, Liu C, Tian N, Zhu M, et al . The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences.2024;79(1). CrossRef

- SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS: Routledge Pallant J. 2020.

- Semaglutide treatment for type 2 diabetes in a patient with chronic myeloid leukemia: A case report and review of the literature Zhang Y, Li A. Open Medicine (Warsaw, Poland).2025;20(1). CrossRef

- PML::RARα+ myeloid cells display metabolic alterations that can be targeted to treat resistant/relapse acute promyelocytic leukemias Zaza A, Zardo G, Banella C, Tucci S, Marinis E, Gentile M, Travaglini S, et al . Leukemia.2025;39(11). CrossRef

- Antiproliferative Impact of Linagliptin on the Cervical Cancer Cell Line Muafaq Said A, Abdulla KN , Ahmed NH , Yasin YS . Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP.2024;25(9). CrossRef

- Inflammasomes in Alveolar Bone Loss Li Y, Ling J, Jiang Q. Frontiers in Immunology.2021;12. CrossRef

- Sulfonylureas for Treatment of Periodontitis-Diabetes Comorbidity-Related Complications: Killing Two Birds With One Stone Yang L, Ge Q, Ye Z, Wang L, Wang L, Mashrah MA , Pathak JL . Frontiers in Pharmacology.2021;12. CrossRef

- Hyperferritinemia and inflammation Kernan KF , Carcillo JA . International Immunology.2017;29(9). CrossRef

- Ferritin in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Not Only a Marker of Inflammation and Iron Overload, but Also a Regulator of Cellular Iron Metabolism, Signaling and Communication Reikvam H, Rolfsnes MG , Rolsdorph L, Sandnes M, Selheim F, Hernandez-Valladares M, Bruserud Ø. International Journal of Molecular Sciences.2025;26(12). CrossRef

- Parathyroid gland function in chronic renal failure Felsenfeld AJ , Llach F. Kidney International.1993;43(4). CrossRef

- Parathyroid hormone, vitamin D, renal dysfunction, and cardiovascular disease: dependent or independent risk factors? Anderson JL , Vanwoerkom RC , Horne BD , Bair TL , May HT , Lappé DL , Muhlestein JB . American Heart Journal.2011;162(2). CrossRef

- Tumor macroenvironment and metabolism Al-Zoughbi W, Al-Zhoughbi W, Huang J, Paramasivan GS , Till H, Pichler M, Guertl-Lackner B, Hoefler G. Seminars in Oncology.2014;41(2). CrossRef

- Metabolites and the tumour microenvironment: from cellular mechanisms to systemic metabolism Elia I, Haigis MC . Nature Metabolism.2021;3(1). CrossRef

- Evaluation of LH, FSH, Oestradiol, Prolactin and Tumour Markers CEA and CA-125 in Sera of Iraqi Patients With Endometrial Cancer Dawood YJ , Mahdi MA , Jumaa AH , Saad R, Khadim RM . Scripta Medica.2024;55(4). CrossRef

- Hematological Adverse Events with Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis Kronick O, Chen X, Mehra N, Varmeziar A, Fisher R, Kartchner D, Kota V, Mitchell CS . Cancers.2023;15(17). CrossRef

- Long-Term Follow-Up in Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Treated With Ponatinib in a Real-World Cohort: Safety and Efficacy Analysis Mela Osorio MJ , Moiraghi B, Osycka MV , Pavlovsky MA , Varela AI , Bendek Del Prete GE , Tosin MF , et al . Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia.2024;24(3). CrossRef

- Balancing the Scales: The Dual Role of Interleukins in Bone Metastatic Microenvironments Dawalibi A, Alosaimi AA , Mohammad KS . International Journal of Molecular Sciences.2024;25(15). CrossRef

- Diabetic Wound Healing Enhancement by Tadalafil Jarad A. Int J Pharm Res Allied Sci..2025. CrossRef

- Study of the cytotoxic and genotoxic effects for fractioniated extracts of convolulus arvensis on bone marrow in mice Said AM , Numan IT , Hamad MN . International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences Received.2013;18:303-305.

- Metformin And Metformin Plus Insulin Combination Effect On Some Apoptosis Factors And Biochemical Parameters In Type 2 Diabetic Patients Zaidan NK , Saifullah PH . Biochemical & Cellular Archives.2020;20(1).

- Cancer-related inflammation and depressive symptoms: Systematic review and meta-analysis McFarland DC , Doherty M, AtkinsonTM , O'Hanlon R, Breitbart W, Nelson CJ , Miller AH . Cancer.2022;128(13). CrossRef

- Physiological Scrutiny to Appraise a Flavonol Versus Statins Hashim WS , Yasin YS , Jumaa AH , Al-Zuhairi MI , Abdulkareem AH . . Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal.;16(1):289-293. CrossRef

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright

© Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Biology , 2026

Author Details