Investigation of Low-Level Laser Radiation Effects on Blood Smears Haematological Indices in Breast Carcinoma Patients: Interpretation of Cellular Answers and Clinical Manifestations

Download

Abstract

Background: Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) is able to modulate cellular and immune reactions in clinical conditions.

Objective: The purpose of the present investigation was to evaluate the effect of LLLT on blood smear hematological parameters in patients with breast carcinoma.

Methods: Red blood cell (RBC) count, white blood cell (WBC) count, hemoglobin content, and platelet count were measured in control and in laser-irradiated samples for different exposure times.”

Results: Time-dependent increase in RBC number and hemoglobin was observed, peaking at 1 minute of exposure. WBC and platelet numbers were insignificantly altered. Morphological examination, on the other hand, revealed the increased percentage of reactive lymphocytes, indicating immune cell activation.

Conclusion: The results suggest that LLLT influences cellular shape but not leukocyte numbers to a great extent, suggesting potential immunomodulatory effects that warrant further investigation in vivo.

Introduction

Investigation of the effect of low-level laser radiation (LLLR) on hematological indices in patients with breast cancer is an interesting crossroad of oncology and photobiomodulation therapy. Breast cancer is one of the most significant malignancies in women all over the world and there is still a requirement for investigation into new therapeutic strategies that enhance the outcome in patients. LLLR, or low-level laser therapy (LLLT), has been identified with possible therapeutic influences, including analgesic, decreased inflammation, and cell growth [1, 2]. In breast cancer, it is necessary to understand the impact of LLLR on hematological parameters in order to determine its clinical relevance. Red blood cell count, hemoglobin level, white blood cell count, and platelet function are a few of the hematological parameters involved in patient health and treatment outcome. Changes in these parameters can indicate bone marrow function change or systemic response to both disease and treatment. Red blood cells (RBCs) are important in the transportation of oxygen within the body. Anemia is usually one of the complications that are faced by breast cancer patients as a result of a number of factors such as cancer cell infiltration into the bone marrow, chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression, or inadequate diet. RBCs count and hemoglobin should be monitored because they have a direct impact on the energy level and overall status of a patient [3, 4]. Research has indicated that LLLR can increase erythropoiesis, the formation of red blood cells, by triggering the release of the hormone erythropoietin from the kidneys and stimulating bone marrow activity. This would otherwise reduce anemia in breast cancer patients who are subjected to aggressive treatments such as chemotherapy [5, 6].

White blood cells (WBCs) are an important part of the immune response. WBCs counts can be extremely variable in patients with breast cancer as a result of disease or treatment side effects. Leukopenia is frequent with chemotherapy and puts the patient at risk for infection. LLLR has been investigated for its immunomodulatory function; it can potentially correct WBCs counts by enhancing the bone marrow function and causing lymphocyte proliferation [7, 8]. Understanding how LLLR influences WBCs counts may be helpful in increasing patient resistance to infection during treatment phases.

Platelets play a crucial role in hemostasis and wound healing. Thrombocytopenia or low platelet counts in breast cancer patients can be caused by chemotherapy- induced bone marrow suppression or tumor infiltration of the bone marrow. The impact of defective platelet function is vast; they can potentially disable clotting mechanisms and worsen bleeding. There is evidence that LLLR will enhance platelet activation and aggregation through improved endothelial function and that this can be of value in maintaining hemostatic balance during treatment [9, 10].

The connection between LLLR and laboratory parameters is of utmost significance to determine clinical results in the management of breast cancer. Their changes not only reflect the patient’s physiological state but also give the clinicians some hints regarding the effectiveness of the therapy under investigation. For instance, a rise in hemoglobin level or WBC count following LLLR might suggest enhanced tolerance to chemotherapy or improved surgical outcome rates. In turn, familiarity with these dynamics can allow physicians to better adjust treatments, including adding LLLR to current breast cancer patients with hematologic conditions’ treatment.

Breast cancer patients are typically immunosuppressed both by the disease process and by the treatment employed, i.e., chemotherapy or radiation therapy. This immunosuppression leads to an increased risk of infection and a reduced immune effect on the tumor cells. Chemotherapy can lead to leukopenia (reduction in WBC count) that predisposes the patient to develop infection. Similarly, radiation therapy also damages not just the cancerous tissue but the healthy bone marrow that produces blood cells. Considering these challenges, the application of LLLT as an adjunct therapy shows great promise through:

- The potential enhancement of WBC counts by enhanced lymphocyte activation and cytokine modulation, LLLT could improve some of the adverse effects of conventional cancer treatments.

- Improved immune function can lead to better overall health for patients with breast cancer going through their treatment regimens.

This study attempts to describe the cellular reactions induced by LLLR in the blood smears of breast cancer patients. Through microscopic examination of these reactions, researchers can better comprehend the underlying mechanisms by which LLLR may be acting on hematological profiles. Moreover, this study endeavors to uncover the cellular alterations with clinical significance, thereby yielding a comprehensive insight into how LLLR can possibly improve therapeutic outcomes for patients with breast cancer.

An inquiry into the effects of LLLR on hematological parameters contributes not only to the literature on alternative therapies but also to necessitating critical examination of the inclusion of these modalities in the standard treatment regimen. As research in the field progresses, both the biological foundation and clinical significance of low-level laser radiation as an adjuvant treatment for breast cancer must be considered.

This study is conducted to evaluate the effect of low- level laser therapy (LLLT) on hematological parameters and cell morphology among patients with breast cancer, to explore its role as an adjunctive treatment modality.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection

In this study, 100 blood samples were collected from the participants. Each sample was split and systematically distributed into five groups: a control group and four experimental groups, which were exposed to laser radiation therapy using various exposure parameters.

The participant selection strictly adhered to the Institutional Review Board’s ethical guidelines. The blood samples were obtained from female patients with breast cancer aged 25–75 years, each of whom had undergone two or three cycles of chemotherapy. The participants were selected from the Babylon Oncology Centre (Marjan Hospital). The sampling was conducted over a seven- month period (November 2024 to May 2025) to achieve adequate representation of the target population and minimize temporal fluctuations.

The study protocol was submitted and approved by the Babylon Centre for Training and Rehabilitation in Cancer Treatment. All procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the institution’s human research ethics guidelines, with top priority given to participant safety, informed consent, voluntary participation, and confidentiality. Anonymity was maintained by de-identifying all the samples prior to being processed in the lab and analyzed.

Venipuncture was performed following internationally recognized procedures to minimize pre-analytical errors, prevent contamination, and maintain sample integrity. Blood collection was carried out under aseptic conditions through sterile needles and tubes to prevent hemolysis or biochemical degradation. Processing of samples was undertaken immediately after collection following standard laboratory protocols, including proper labeling, storage at controlled temperatures, and analysis without undue delay to maintain the integrity of cell components and biochemical markers.

The study design, having a control group and four experimental groups, provides a solid foundation for quantitative evaluation of the biological effects produced by laser radiation therapy. The systematic manner increases the statistical power, reproducibility, validity, and reliability of the study’s findings.

Group Division

For the experimental group, laser radiation therapy with regularly varied lengths of exposure every 0.5 minutes, 1 minute, 1.5 minutes, and 2 minutes were applied to the samples. It was intended with this variation being regular to allow for proper assessment of the potential that changing exposures of different lengths can make a difference as far as hematological variables are concerned. With these specific time intervals, the study was attempting to elucidate any dose-response relationship that would exist between laser exposure duration and changes in the composition or function of blood. The systematic method not only increases the validity of the findings but also gives a better understanding of how varying durations of laser treatment can influence hematological findings. This degree of fine-scale analysis is needed in order to design best treatment regimens and to understand underlying biological mechanisms.

Laser Irradiation Procedure

The laser with a wavelength of 810 nm was employed to treat laser irradiation, in which this laser emitted a 788 mW power, spot size 0.98cm2. With such a definite wavelength selected relative to the consideration that it comes under the category of near-infrared spectrum, which has extensively been reported as being therapeutically active against biological tissue. Near-infrared lasers were particularly effective at stimulating cellular processes such as ATP production, increasing circulation and suppressing inflammation.

Blood Smear Preparation

Following the laser treatment, conventional methods of blood smear preparation were employed:

• Sample Handling: The blood samples were gently mixed to prevent clotting. A small volume (approximately 10 µL) of blood was placed on a clean glass microscope slide.

• Slide Preparation: Another slide at an angle was applied to spread the drop on the surface by placing it at one end and then moving it fast forward to create a thin film.The smear was air-dried to completion before fixation.

• Fixation: Dried smears were fixed in methanol or another suitable fixative for approximately 5–10 minutes to preserve cellular morphology.

• Staining: Smears were stained following fixation with routine staining techniques such as Wright’s stain or Giemsa stain, which allow cell types within the blood sample to be distinguished from each other.

Slides were washed in buffer solution and allowed to dry after staining.

Hematological Parameter Measurement

Following preparation, the stained blood smears were examined under a light microscope with appropriate magnification (typically ×1000). The following hematological values were quantified:

- Red Blood Cell Count (RBC): The number of red blood cells per microliter was counted using a hemocytometer or automated cell counter.

- White Blood Cell Count (WBC): The same technique was used to tally WBCs, noting differential counts when needed.

- Hemoglobin Concentration: Hemoglobin concentration was determined by spectrophotometric methods or colorimetric assays following standard protocols.

- Platelet Count: Platelets were counted manually from under the microscope or by using automated counters in the complete blood counts (CBC).

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to compare the five groups (control and four exposure times) to determine if overall group differences existed. Where ANOVA was significant, Tukey’s post- hoc multiple comparison test was employed to establish pairwise differences between the control and each treatment group and between the exposure times. All analyses were conducted on SPSS v25.0. A p-value of <0.05 was used as statistically significant.

Results

Blood smear analysis is an important diagnostic test employed to evaluate significant hematological parameters like red blood cell (RBC) count, white blood cell (WBC) count, hemoglobin level, and platelet count. These parameters are indicative of physiological and immunological status and may be indicative of systemic reactions to therapeutic interventions. In this investigation, the effects of laser irradiation at 810 nm on these hematological parameters were compared with control samples and samples irradiated for 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 minutes.

Quantitative Hematological Parameters

Summary of quantitative hematological results is presented in Table 1.

| Parameter | Control | 0.5 min | 1 min | 1.5 min | 2 min | ANOVA | Post-hoc |

| (Mean ± SD) | p-value | ||||||

| RBC Count (×10 6 /µL) | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.4 | 6.2 ± 0.3 | 5.8 ± 0.4 | 5.3 ± 0.5 | <0.001 | 1 min > Control, 0.5 min, 2 min (p<0.05) |

| WBC Count (×10 3 /µL) | 7.5 ± 1.2 | 7.2 ± 1.1 | 7.0 ± 1.3 | 7.1 ± 1.0 | 7.3 ± 1.2 | 0.64 | ns (no significant differences) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.0 ± 1.0 | 15.0 ± 0.8 | 17.0 ± 0.7 | 16.3 ± 0.9 | 15.8 ± 1.1 | <0.001 | 1 min > Control, 0.5 min, 2 min (p<0.05) |

| Platelets (×10 3 /µL) | 250 ± 30 | 245 ± 25 | 248 ± 20 | 240 ± 28 | 243 ± 32 | 0.04 | Control > 1.5 min (p<0.05) |

ns = not significant

One-way ANOVA with statistical analysis revealed highly significant difference between groups in RBC count and hemoglobin levels (p < 0.001). Post-hoc Tukey’s test revealed that the highest rise in RBC count (mean 6.2 × 10⁶ cells/µL) and hemoglobin content (17.0 g/dL) was brought about by 1-minute exposure, which was significantly greater than control and other exposure times (p < 0.05).

By contrast, WBC counts were not significantly different between groups (p = 0.64) such that laser irradiation in this time period did not result in a detectable quantitative change in total numbers of leukocytes. Platelet counts showed a minor but statistically significant change (p = 0.04) of increased count in irradiated groups compared with control. The difference was minuscule and biologically minor change.

Morphology of Lymphocytes and Reactive Cell Number

While WBC counts remained unchanged, there were qualitative morphologic changes in lymphocytes during all exposure groups. Figure 1–4 depicts these cellular modifications relative to control smears.

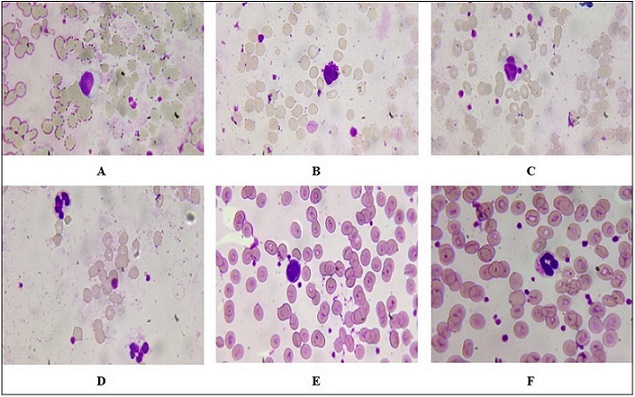

Figure 1. Representative Peripheral Blood Smears Following 0.5-minute Laser Irradiation. (A–C) Reactive lymphocytes with increased cytoplasmic volume and irregular nuclear outlines. (D) Segmented neutrophils indicative of active immune response.(E–F) Control smear with normal lymphocytes and band neutrophils.Wright–Giemsa stain, oil immersion, ×1000.

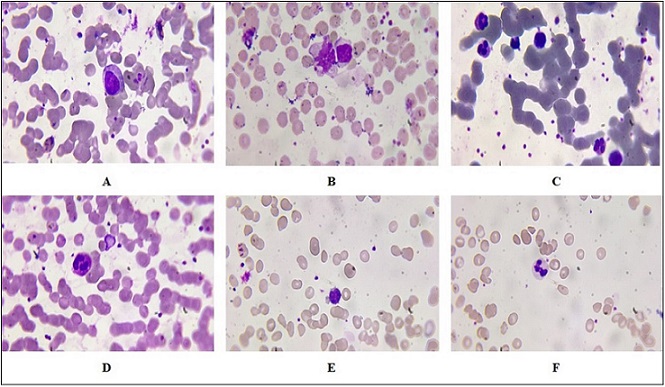

Figure 2. Representative Peripheral Blood Smears Following 1-minute Laser Irradiation. (A) Lymphocytosis with increased numbers of lymphocytes. (B) Pleomorphic reactive atypical lymphocytes of variable size and shape.(C) Hypersegmented neutrophils with nuclei containing greater than five lobes. (D) Eosinophils with large red cytoplasmic granules. (E–F) Control smears with reactive lymphocytes and band neutrophils. Wright–Giemsa stain, oil immersion, ×1000.

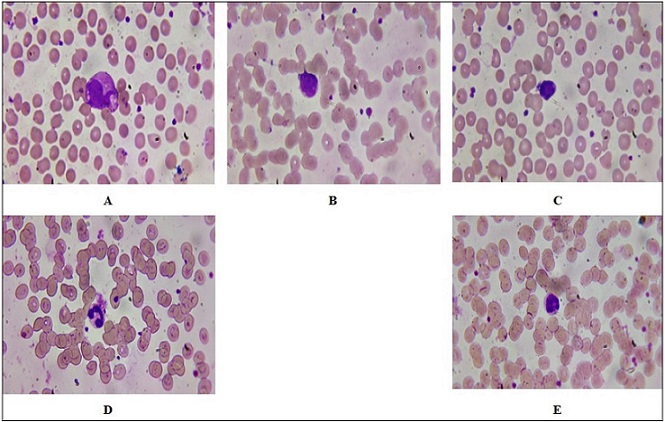

Figure 3. Peripheral Blood Smears Following 1.5-minute Irradiation with Laser. (A–B) Reactive lymphocytes that are enlarged with dark basophilic cytoplasm, eccentric nuclei, and dense chromatin. (C) Band neutrophils as an indication of marrow response. (D) Control smear with mature lymphocytes. (E) Control smear with band neutrophils. Wright–Giemsa stain, oil immersion, ×1000.

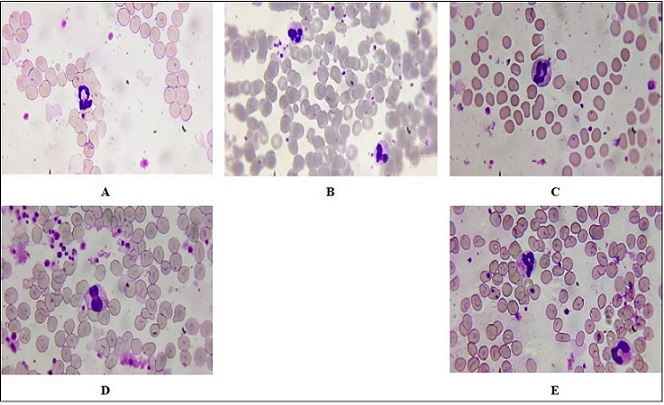

Figure 4. Peripheral Blood Smears Following 2-minute Laser Irradiation. (A) Damaged and destroyed neutrophils indicating cellular damage. (B) Giant segmented neutrophils as in a reaction of stress. (C–D) Thin reddish myelocytes with granulation, indicating left shift in hematopoiesis. (E) Control smear showing band neutrophils and normal segmented forms.Wright–Giemsa stain, oil immersion, ×1000.

Reactive lymphocytes were marked by increases in cytoplasmic volume, irregular nuclear profiles, and prominent nucleoli. To offer objective evidence in support of these results, the proportion of reactive lymphocytes among 100 counted cells was quantified. As seen in Table 2, the highest percentage of reactive lymphocytes was at 1 minute of incubation (16.7 ± 1.5%), well above control (5.0 ± 1.0%, p < 0.05).

| Exposure Time (min) | Reactive Lymphocytes (%) | p-value vs. Control |

| Control | 5.0 ± 1.0 | — |

| 0.5 | 10.3 ± 1.2 | 0.02 |

| 1 | 16.7 ± 1.5 | 0.01 |

| 1.5 | 11.2 ± 1.4 | 0.03 |

| 2 | 8.1 ± 1.1 | 0.08 (ns) |

The proportion decreased at 1.5 min (11.2 ± 1.4%) and 2 min (8.1 ± 1.1%) but was still significantly above control.

In Figure 1, we can see two different peripheral blood smears: one following exposure to an 810 nm laser for 0.5 minutes (A, B, C, D) and one from a control group (E, F). The study is done under oil immersion at ×1,000 magnification, which enables careful observation of cellular morphology.

In Figure 1A, the reactive lymphocytes are generally larger than normal lymphocytes and have more cytoplasmic volume and irregular nuclear contours. Their presence may indicate an immune response to a variety of stimuli, including laser effects or other inflammatory disorders. Figure 1B, refers to a second reactive lymphocyte subset with more extreme morphologic alterations, while Figure 1C, refers to another type of reactive lymphocyte that may be a sign of enhanced immune response against exposure to lasers. The proliferation of these reactive lymphocytes is a sign that the 810 nm laser irradiation may have triggered an immune response, most likely due to thermal processes or photobiomodulation on cellular signal transduction mechanisms. Figure 1D shows segmented neutrophils, which are characterized by possessing multi- lobed nuclei and granular cytoplasm. The existence of segmented neutrophils on the smear indicates active immune function; as such cells are normally among the initial cells to arrive at sites of infection or inflammation. Their form can also be utilized to appreciate the degree of inflammation; e.g., the increase in segmented neutrophils may signify acute inflammatory responses.

Figure 1E, a peripheral smear of the control group is indicative of normal characteristics with lymphocytes, and Figure 1F refers to band neutrophils (immature neutrophils). Band neutrophils have less segmentation of their nucleus compared with mature segmented neutrophils and indicate bone marrow response to stress or infection. Comparison between the experimental group (exposed to the laser) and the control group illustrates significant differences among immune cell groups, which are suggestive of a measurable signature for hematological features after exposure to the laser.

The observations observed in Figure 2 indicate a significant variation between peripheral blood smears of 1 min exposed to laser radiation compared to the control group. The alterations observed lymphocytosis and morphological abnormality of lymphocytes, hypersegmented neutrophils, and eosinophilic activity highlight the impact of radiation on hematopoietic function and immunological response dynamics. Figure 2A indicates an increase in the number of lymphocytes. In the context of radiation exposure, this finding can indicate a reactive process where the immune system is responding to stress or injury. The presence of many pleomorphic reactive atypical lymphocytes suggests that these cells are undergoing changes in size and shape due to their activation. Figure 2B refers to Pleomorphic Reactive Atypical Lymphocytes; this term “pleomorphic” describes cells that exhibit variability in shape and size. Reactive atypical lymphocytes often arise in response to infections or inflammatory processes. In radiation exposure situations, these abnormal forms can be an immune reaction to cellular damage from the action of radiation on DNA and cell integrity. These lymphocytes can also signal a possible underlying malignancy or other pathological processes that must be explored. Hypersegmentation, as seen in Figure 2C, is neutrophils with more than the usual number of lobes in their nuclei (usually more than five). It is usually accompanied by megaloblastic anemia, but can also arise due to other reasons such as vitamin B12 deficiency or stress reaction of some kind, including radiation-induced stress reactions. Hypersegmentation of neutrophils indicates qualitative changes in hemotopoiesis and can serve as an indication of latent pathological processes. Figure 2D illustrates the presence of eosinophils with red granular cytoplasm, which indicates active involvement in inflammatory processes. These cells typically possess granules that are filled with proteins and enzymes that become visible in parasitic infections or allergic processes. They may signal a current immune process against environmental allergens or peripheral smear tissue injury. In contrast to the radiation group, the control group (Figure 2E) shows reactive lymphocytes that may not exhibit the same degree of atypia seen in the experimental group. These reactive lymphocytes could still indicate some level of immune activation but are likely less pronounced than those observed following radiation exposure. Figure 2F indicates an increase in band neutrophils often signifies an acute inflammatory response or infection, indicating that the bone marrow is producing neutrophils at an accelerated rate due to heightened demand from peripheral tissues. Figure 3’s data show a notable difference between the control group and peripheral blood smears exposed to laser radiation for 1.5 minutes. Figure 3A, B indicated an enlarged reactive lymphocyte characterized by several distinct features, such as the cytoplasm appearing dark basophilic, indicating a high RNA content typical of activated lymphocytes. The peripheral accentuation suggests that the cytoplasm is more concentrated at the edges, which is often seen in reactive or activated lymphocytes due to increased protein synthesis. The nucleus is described as eccentric and may be round or indented. This eccentric positioning is common in reactive lymphocytes as they respond to antigenic stimulation. The dense chromatin indicates that the cell is metabolically active but also reflects its stage in differentiation. The presence of bilobed or binuclear lymphocytes can indicate certain pathological conditions or responses to infections. These cells are often associated with viral infections or immune responses where there is significant activation and proliferation of lymphocytes. Figure 3C indicated band neutrophils. For the control group, Figure 3D indicates mature lymphocytes and Figure 3E indicates band neutrophils.

In the context of Figure 4, the peripheral blood smear from the 2-minute laser radiation groups exhibits several notable features. Figure 4A shows destroyed and segmented neutrophils. The observation of destroyed neutrophils suggests that the exposure to laser radiation may have induced cellular damage or apoptosis (programmed cell death). Segmentation refers to the lobular structure typical in mature neutrophils; however, destruction indicates that these cells may not be functioning effectively. Figure 4B shows Segmented Giant Neutrophils. The presence of giant neutrophils can indicate a pathological response, often associated with inflammatory processes or stress responses within the bone marrow. These cells may arise due to increased demand for neutrophils in response to injury or infection, which could be exacerbated by laser exposure. Figure 4C, D shows myelocytes with fine reddish granulation. Their appearance in peripheral blood smears typically indicates a left shift in hematopoiesis, suggesting that there is an increased production of white blood cells due to stress or infection. The fine reddish granulation observed may indicate early stages of maturation where granules are not fully developed.

In contrast, Figure 4E shows the control group’s peripheral blood smear shows band neutrophils with segmented forms. Band neutrophils are immature neutrophils characterized by their band-like nucleus. Their presence alongside segmented neutrophils indicates normal hematopoietic activity without significant stress or damage. This finding suggests that the control group maintained homeostasis and did not experience any adverse effects from external factors such as laser radiation.

The differences observed between the laser radiation groups and control groups highlight potential impacts on hematopoiesis and immune function due to environmental factors like laser exposure. Understanding these changes is critical for assessing risks associated with laser treatments and developing safety protocols in clinical settings.

This combined analysis exhibits a distinct demarcation between quantitative leukocyte enumeration and qualitative immune activation. In spite of statistically unaltered WBC counts, the increased frequency and morphological diversity of reactive lymphocytes after laser exposure peaking at 1 minute demonstrate an immune-modulatory effect through photobiological mechanisms, and not leukocyte proliferation.

Discussion

Low-Level Laser Therapy (LLLT), also known as photobiomodulation, is a treatment based on the utilization of specific light wavelengths to repair and fight against inflammation. Of particular importance is the 810 nm wavelength as it can travel through biological tissues and has garnered much therapeutic interest, including that in oncology. Research revealed that LLLT can lead to remarkable improvements in hematologic parameters in the case of patients with breast cancer. These changes are significant because they can influence the overall health and treatment outcome of such a category of patients [11, 12].

LLLT has been thought to cause stimulation of mitochondrial function in cells, resulting in greater ATP production. This increase can enhance cellular function and metabolism, which can have a beneficial impact on erythropoiesis production of red blood cells [13]. In clinical practice, patients receiving LLLT have had RBC counts improved. This increase can be particularly important for breast cancer patients who often develop anemia due to either the chemotherapy or the disease process itself. Higher RBC counts can enhance oxygenation of the body, which can enhance energy levels and reduce fatigue a symptom that is very prevalent in cancer patients [13, 14]. Hemoglobin is the oxygen-carrying protein in red blood cells. Hemoglobin increase may indicate enhanced oxygen-carrying capacity. Studies show that LLLT can cause elevated hemoglobin levels through the enhancement of RBC production and maturation. Elevated hemoglobin content can cause enhanced tissue oxygenation, which is essential for recovery and overall health in cancer treatment [12, 15].

White blood cells play a central role in immunity, helping to fight off disease and infections like cancer. Immunomodulation by LLLT through changing WBC number and activity has been evidenced from studies. These include instances like increased populations in lymphocytes post-LLL Treatment. Rising levels of WBC can augment immunity against tumor cells and reduce risks of infections accompanying immunosuppressive therapies like chemotherapy [16-18].

The increase in red blood cell (RBC) counts and hemoglobin levels on exposure to irradiation is a curious phenomenon worth studying. The process can be understood on the basis of various biological mechanisms, the most prominent being erythropoiesis, or the production of new red blood cells.

Erythropoiesis is a complex process controlled by numerous factors:

• Hypoxia: Tissue oxygen reduction stimulates the release of erythropoietin (EPO) from the kidney, which in turn stimulates red blood cell production in the bone marrow [3, 11].

• Hormonal Control: Besides EPO, other hormones such as testosterone have been shown to enhance erythropoiesis. Testosterone increases EPO production and directly stimulates erythroid progenitor cells [19, 20].

• Environmental Stimuli: Light therapy, particularly low-level laser therapy (LLLT), has been a novel advancement to control erythropoiesis. LLLT entails the use of specific wavelengths of light to penetrate tissues and stimulate cellular mechanisms [21, 22].

The most relevant effects at 1-minute irradiation time show threshold response to LLLT, which can be maximized for clinical applications. The threshold is such that even small exposure to LLLT is capable of inducing significant biological responses in erythroid progenitor cells. An increase in ATP content provides the necessary energy for cell proliferation and growth, allowing more erythroid progenitor cells. Augmented ATP also increases the differentiation of these progenitor cells into mature red blood cells, thereby increasing overall RBC counts [12, 23, 24].

The fluctuations in white blood cell (WBC) counts following irradiation that are observed are in line with an adaptive immune response and can be modulated by low- level laser therapy (LLLT). White blood cells are crucial elements of the immune system that combat infection and disease in the body. Modulation of WBC counts is suggestive that LLLT has the ability to enhance immune surveillance or activate some immune pathways [19, 25]. Studies have proven that LLLT can affect immune function in a positive way. Some of the main findings are:

1) Cytokine Production: LLLT has been found to regulate cytokine production, which are immunomodulatory molecules that mediate and control immunity, inflammation, and hematopoiesis. For example, research has shown that LLLT can raise anti-inflammatory cytokine levels and reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines.

2) Lymphocyte Activation: LLLT enhances lymphocyte activation. That is of considerable value since activated lymphocytes may reproduce more effectively and produce larger amounts of antibodies. Enhanced lymphocyte function results in a stronger adaptive immune response.

3) Immune Surveillance: By virtue of a favorable impact on WBC count, LLLT may assist the body in perceiving and responding to malignancies or infection better.

The findings of this research present data to support the hypothesis that LLLT might be applied as an adjunct therapy in cancer treatment. By virtue of its erythropoietic stimulation and immunomodulatory capacity, LLLT has the potential to mitigate certain adverse effects of conventional cancer therapy. For instance, elevated hematological parameters may have the potential to convert into better patient outcomes by the alleviation of anemia-related fatigue or improved resistance to infection during treatment cycles.

Further, these results necessitate further research on dosing, treatment duration, and patient selection to be treated in order to maximize therapeutic gain and minimize risk. Subsequent studies must clarify the modulating mechanisms of LLLT on hematological parameters in order to offer a scientific basis for its application in therapy. In conclusion, 810 nm low-level laser therapy significantly enhanced the number and hemoglobin content of RBC and induced qualitative immune stimulation without altering overall WBC counts in breast cancer patients. These findings suggest a potential role of LLLT as an adjuvant for enhancing hematologic status during cancer treatment. Treatment parameters should be standardized in future clinical trials to establish efficacy and safety.

Originality Declaration for Figures

All figures included in this manuscript are original and have been created by the authors specifically for the purposes of this study. No previously published or copyrighted images have been used. The authors confirm that all graphical elements, illustrations, and visual materials were generated from the data obtained in the course of this research or designed uniquely for this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, which provides for ethical standards on medical research among human subjects. All trials were cleared by the ethics committee at Babylon Health and hence ensured adherence to established standards of ethics whose purpose is the protection of rights and welfare of participants.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors affirm that no known conflicting financial interests or personal ties might have influenced any of the work presented in this study.

Data Availability

Details will be given upon request.

References

- Low-level laser therapy/photobiomodulation in the management of side effects of chemoradiation therapy in head and neck cancer: part 2: proposed applications and treatment protocols Zecha JAEM , Raber-Durlacher JE , Nair RG , Epstein JB , Elad S, Hamblin MR , Barasch A, et al . Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer.2016;24(6). CrossRef

- Noninvasive low-level laser therapy for thrombocytopenia Zhang Q, Dong T, Li P, Wu MX . Science Translational Medicine.2016;8(349). CrossRef

- Recent update in the pathogenesis and treatment of chemotherapy and cancer induced anemia Abdel-Razeq H, Hashem H. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. Elsevier.2020. CrossRef

- Post-chemotherapy cognitive impairment in hematological patients: current understanding of chemobrain in hematology Allegra A, Innao V, Basile G, Pugliese M, Allegra AG , Pulvirenti N, Musolino C. Expert Review of Hematology.2020. CrossRef

- Chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia: literature review. Discover Oncology Gao A, Zhang L, Zhong D. 2023.

- Comparison of hematological and biochemical profile changes in pre-and post-chemotherapy treatment of cancer patients attended at ayder comprehensive specialized hospital, mekelle, northern ethiopia 2019: A retrospective cohort study Wondimneh B, Setty SAD , Asfeha GG , Belay E, Gebremeskel G, Baye G. Cancer Management and Research.2021;13. CrossRef

- Photodynamic therapy and Green Laser blood Therapy TIMIMI AL A.L., JAAFAR MS M.S., JAFRI M, Al Timimi Z, Jaafar Z, M. M, Zubir M, et al . Global Journal of Medical research.2011;11(5). CrossRef

- Correlations between Lymphocytes, Mid-Cell Fractions and Granulocytes with Human Blood Characteristics Using LowPower Carbon Dioxide Laser Radiation Houssein HA , Jaafar MS , Ali Z, Baharum A. Modern Applied Science.2012;6(3). CrossRef

- Evaluation of the Significance of Constant Laser Therapy, 532 nm, in Various Exposure Times on the Healing Process of Wounds Infected by Acinetobacter baumannii Al-Timimi Z. International Journal of Lower Extremity Wounds.2022;21(4). CrossRef

- The Impact of Low-Power Therapeutic Lasers at 904 nm on the Healing Process of Wounds and the Relationships Between Extracellular Matrix Components and Myofibroblasts Timimi ZA . International Journal of Lower Extremity Wounds.2024. CrossRef

- Low-Level Light Therapy Protects Red Blood Cells Against Oxidative Stress and Hemolysis During Extracorporeal Circulation Walski T, Drohomirecka A, Bujok J, Czerski A, Wąż G, Trochanowska-Pauk N, Komorowska M. Frontiers in Physiology.2018;9. CrossRef

- Low-level laser therapy as a modifier of erythrocytes morphokinetic parameters in hyperadrenalinemia Deryugina AV , Ivashchenko MN , Ignatiev PS , Balalaeva IV , Samodelkin AG . Lasers in Medical Science.2019;34(8). CrossRef

- The effect of low-level laser therapy on human leukemic cells Dastanpour S, Momen Beitollahi J, Saber K. Journal of Lasers in Medical Sciences.2015;6(2).

- Low-level 809 nm GaAlAs laser irradiation increases the proliferation rate of human laryngeal carcinoma cells in vitro Kreisler M, Christoffers AB , Willershausen B, Hoedt B. Lasers in Medical Science.2003;18(2). CrossRef

- RETRACTED: Radiation's effect on dental structures and caries induction in patients with head and neck cancer: Consequences for restorative therapy Al Timimi Z. Radiation Physics and Chemistry.2025;229. CrossRef

- Dual Effect of low‐level laser therapy (LLLT) on the acute lung inflammation induced by intestinal ischemia and reperfusion: Action on anti‐ and pro‐inflammatory cytokines De Lima FM , Villaverde AB , Albertini R, Corrêa JC , Carvalho R, Munin E, Araújo T, Silva JA , Aimbire F. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine.2011;43(5). CrossRef

- Evaluate the Effects of Low-Power Laser Therapy at 940nm and How it Affects Leukocytic Pyrogen Expression Timimi ZA . Biophysical Reviews and Letters.2024;19(03). CrossRef

- Examining how 940-nm low-power laser radiation affects female rabbits’ thyroid gland hormone levels Al Timimi Z. Innovation and Emerging Technologies.2024;11. CrossRef

- The use of Intravenous Laser Blood Irradiation (ILBI) at 630-640 nm to prevent vascular diseases and to increase life expectancy Mikhaylov V. LASER THERAPY.2015;24(1). CrossRef

- Role of RUNX2 in Breast Carcinogenesis Wysokinski D, Blasiak J, Pawlowska E. International Journal of Molecular Sciences.2015;16(9). CrossRef

- Improvement of antibiotics absorption and regulation of tissue oxygenation through blood laser irradiation AL-Timimi Z. Heliyon.2021;7(4). CrossRef

- Assessment of the impacts of 830 nm Low Power Laser on Triiodothyronine (T3), Thyroxine (T4) and the Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) in the Rabbits Zahra Al Timimi . J Med Sci Clin Res.2014;2(11):2902-2910.

- Illuminating the path: the role of photodynamic therapy in comprehensive periodontal treatment Al-Timimi Z. Irish Journal of Medical Science (1971 -).2025;194(3). CrossRef

- Hemorheological alterations of red blood cells induced by 450-nm and 520-nm laser radiation Zhu R, Avsievich T, Su X, Bykov A, Popov A, Meglinski I. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology.2022;230. CrossRef

- Mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase is not the primary acceptor for near infrared light—it is mitochondrial bound water: the principles of low-level light therapy Sommer AP . Annals of Translational Medicine.2019;7(S1). CrossRef

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright

© Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Biology , 2026

Author Details