Immunohistochemical Evaluation of EMT-related Adhesion Markers in Odontogenic Lesions: Implications for Tissue Integrity and Tumor Behavior

Download

Abstract

Background: Epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) is increasingly recognized as an important contributor to the invasive behavior of odontogenic tumors. However, comparative analyses of EMT-associated biomarkers across different odontogenic lesions remain limited. A clearer understanding of EMT-related alterations may help differentiate lesion biology and improve diagnostic interpretation.

Aim: To evaluate and compare the expression profiles of key EMT-related markers Twist, Snail, E-cadherin, and integrin-β1 in ameloblastoma (ABL), keratocystic odontogenic tumor (KOT), orthokeratinizing odontogenic keratocyst (OOK), and dental follicle (DF) tissues.

Methods: Seventy cases were analyzed: 21 ABL, 31 KOT, 8 OOK, and 10 DF. All samples underwent histopathological reevaluation followed by standardized immunohistochemical staining. Staining intensity, percentage of positive cells, and H-scores were independently assessed by two blinded pathologists. Statistical analyses included Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis tests; significant Kruskal–Wallis results were followed by Dunn–Bonferroni post hoc comparisons. Effect sizes were calculated (r for Mann–Whitney, η² for Kruskal–Wallis). Data were reported as median (IQR) or mean ± SD, depending on distribution characteristics.

Results: ABL exhibited the highest frequency of Snail positivity (42.9%) together with marked reductions in E-cadherin and integrin-β1 expression, consistent with EMT-associated alterations. Snail expression was significantly higher in ABL than in both KOT and OOK (p < 0.01). E-cadherin and integrin-β1 levels were significantly lower in ABL and KOT compared with DF (p < 0.05). Twist expression did not differ significantly among lesion types (p > 0.05). No significant differences were found between solid and unicystic ABL subtypes.

Conclusion: EMT-related markers demonstrate distinct expression patterns across odontogenic lesions. Twist shows limited discriminatory value, whereas the combined profile of elevated Snail and reduced adhesion molecules (E-cadherin, integrin-β1) more reliably reflects EMT activity in ameloblastoma. These findings underscore the heterogeneous nature of EMT involvement and highlight the need for further molecular and functional studies clarifying its mechanistic contribution to odontogenic tumor behavior.

Introduction

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a biological process in which epithelial cells lose intercellular junctions and acquire mesenchymal characteristics, resulting in increased motility and invasive potential [1-3]. Although EMT has been well characterized in embryogenesis, fibrosis, and carcinoma progression, its relevance in odontogenic pathology has only recently attracted significant scientific interest. EMT-associated transcription factors such as Snail, Slug, and Twist, as well as molecules regulating adhesion and cytoskeletal reorganization, are known to influence epithelial plasticity and tissue invasion in various neoplasms [4-9].

Ameloblastoma is a benign but locally aggressive odontogenic epithelial tumor characterized by infiltrative growth and a high recurrence rate. Several studies have reported altered expression of EMT-related molecules, including Twist and Snail, suggesting a potential contribution of EMT to its invasive behavior [10]. However, current data remain limited, fragmented, and often contradictory. Moreover, the mechanistic involvement of EMT pathways in the biological differences between solid and unicystic variants of ameloblastoma has not been fully elucidated.

Parakeratinizing odontogenic keratocyst (previously reclassified as keratocystic odontogenic tumor, KOT) represents another odontogenic lesion notable for its high recurrence rate and aggressive growth pattern. In contrast, the orthokeratinizing variant (OOK) exhibits a markedly more indolent clinical course. Despite well-recognized differences in their biological behavior, the extent to which EMT contributes to these distinctions remains unclear. The ongoing debate regarding whether parakeratinizing lesions represent true tumors or developmental cysts highlights the need for molecular-level investigations [11–13].

Taken together, the contemporary literature lacks a comprehensive comparative analysis of EMT-related proteins in ameloblastoma, KOT, OOK, and normal odontogenic epithelium.

We hypothesized that odontogenic lesions with more aggressive clinical behavior, such as ameloblastoma and KOT, would exhibit increased expression of EMT- promoting markers (Twist and Snail) and reduced expression of epithelial adhesion markers (E-cadherin), whereas OOK and normal odontogenic epithelium would retain a more epithelial molecular profile, reflecting lower invasive potential. To address this hypothesis, the present study evaluates the expression patterns of key EMT markers Twist, Snail, E-cadherin, and integrin-β1 across these lesions to better characterize their potential involvement in tumor behavior, epithelial plasticity, and differential aggressiveness.

Materials and Methods

A total of 70 cases were included in this study: 31 keratocystic odontogenic tumors (KOT), 8 orthokeratinizing odontogenic keratocysts (OOK), and 21 ameloblastomas (ABL). Ten dental follicle (DF) tissues served as the control group. All hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained slides were re-evaluated, cases were classified into histological subtypes, and corresponding paraffin blocks were selected for immunohistochemical investigation.

Histopathological assessments were performed using an Olympus BX-51 light microscope (Olympus Microsystems America, Inc.). Clinical information, including patient age, sex, and anatomical site, was recorded for all cases. The type of keratinization was assessed in odontogenic keratocysts, and tumor subtypes were documented in ameloblastoma cases.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic staining in sections stained with Twist and Snail antibodies, and membranous staining in sections stained for E-cadherin and β1-integrin, were considered positive. For Twist, Snail, and E-cadherin, the percentage of positive cells was determined by calculating the ratio of stained to total cells in four high-power fields. The percentage of stained cells was scored as follows: 1 (+) for <25%, 2 (+) for 25–50%, and 3 (+) for >50% [14].

Staining intensity was scored from 1 to 3 based on signal strength. An immunoreactive H-score was calculated by multiplying the percentage score by the intensity score [15]. For integrin-β1, assessment was based on staining intensity.

The evaluation of staining intensity followed the criteria reported by Modolo et al. and Wahlgren et al. [16, 17]. To ensure the reproducibility and validity of the sample, only cases meeting predefined criteria were included.

2.1 Inclusion criteria:

• Histopathologically confirmed diagnosis of ameloblastoma (solid or unicystic type), parakeratinizing odontogenic keratocyst (KOT), or orthokeratinizing odontogenic keratocyst (OOK).

• Availability of adequately preserved paraffin blocks suitable for repeat immunohistochemical analysis.

•Availability of complete clinical data (age, sex, anatomical site).

• Absence of prior treatment that could influence marker expression (surgery or medical therapy).

2.2 Exclusion criteria:

• Odontogenic lesions other than the three analyzed entities.

• Poor-quality samples (severe fixation artifacts, necrosis, insufficient cellularity).

• Recurrent cases lacking primary tissue material.

• Incomplete clinicopathological data.

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 4-µm paraffin sections using a standard indirect immunoperoxidase procedure. The following primary antibodies were used:

•Twist: monoclonal antibody (clone Twist2C1a), Abcam, UK; dilution 1:100

•Snail: monoclonal antibody (clone EPR17819), Abcam; dilution 1:200

•E-cadherin: monoclonal antibody (clone NCH-38), Dako/Agilent; dilution 1:100

• Integrin-β1 : monoclonal antibody (clone P5D2), Millipore/Sigma; dilution 1:150

Antigen retrieval was carried out in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95–98 °C for 20 minutes, followed by cooling to room temperature. Visualization was achieved using the EnVision™ polymer detection system (Dako) and DAB chromogen. Negative controls were prepared by omitting the primary antibody.

Immunohistochemical evaluation was independently performed by two qualified morphologists blinded to clinical data and to each other’s results. Each observer independently assessed the percentage of positive cells, staining intensity, and calculated the H-score according to a unified protocol. Interobserver agreement was evaluated using Cohen’s kappa coefficient and intraclass correlation (ICC). Discrepancies were resolved by joint re-evaluation and consensus.

Statistical Analysis

To ensure robust statistical evaluation, in addition to the nonparametric Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests, extended analytical methods were applied. When the Kruskal–Wallis test indicated a significant effect, post hoc multiple comparisons were carried out using the Dunn–Bonferroni test with correction for multiple testing. For pairwise comparisons using the Mann–Whitney test, effect sizes (r = Z/√N) were calculated to quantify the strength of differences between groups. For the Kruskal– Wallis test, effect size was expressed as η² (eta squared). Data were presented as median (IQR) or mean ± SD, depending on distribution characteristics. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, with adjustment for multiple comparisons where appropriate. This approach ensured a more precise interpretation of statistical significance and allowed quantitative assessment of the magnitude of observed effects.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted using archival, fully anonymized paraffin-embedded tissue blocks obtained during routine diagnostic procedures. No patient- identifying information was available, and no interventions or contact with human subjects were performed. According to the institutional policies of the Azerbaijan Medical University and the Department of Oral Pathology at Ankara Gazi University, such retrospective, non- interventional studies based on fully anonymized material are exempt from formal review by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

The study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision), international biomedical ethics standards, and institutional regulations regarding the confidentiality and anonymization of medical data.

Results

This study included a total of 70 cases, comprising 21 ameloblastomas (ABL), 31 keratocystic odontogenic tumors (KOT), 8 orthokeratinizing odontogenic keratocysts (OOK), and 10 dental follicles (DF), which served as the control group. Demographic characteristics of all cases, including age, sex distribution, and anatomical localization, are summarized in Table 1.

| Group | N | Mean age (years) | Male (n) | Female (n) |

| ABL | 21 | 44 | 10 | 11 |

| KOT | 31 | 36 | 18 | 13 |

| OOK | 8 | 41 | 5 | 3 |

| DF | 10 | 23 | 5 | 5 |

Quantitative analysis demonstrated marked differences in adhesion-related marker expression. The mean E-cadherin H-score was lowest in ameloblastoma (0.71), intermediate in KOT (1.42), and highest in OOK (3.50), while dental follicle tissues showed consistently strong membranous expression. Similarly, integrin-β1 expression was reduced in ameloblastoma and KOT compared with dental follicles, confirming impaired cell–matrix adhesion in biologically more aggressive lesions.

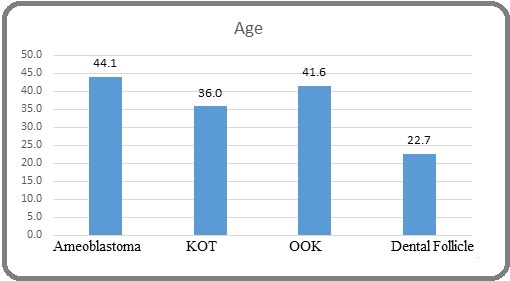

Figure 1 illustrates the mean age distribution across the study groups (ABL, KOT, OOK, and DF).

Figure 1. Mean Age Distribution Across the Study Groups.

Consistent with the demographic data summarized in Table 1, ameloblastomas (mean age 44.1 years) and OOK lesions (41.6 years) predominantly occurred in middle-aged individuals, whereas KOTs showed a slightly younger age profile (36.0 years). In contrast, dental follicles, used as the control group, were observed in significantly younger patients (mean age 22.7 years). The diagram emphasizes the distinct age-related patterns of odontogenic lesions, supporting the known epidemiological characteristics of these pathologies.

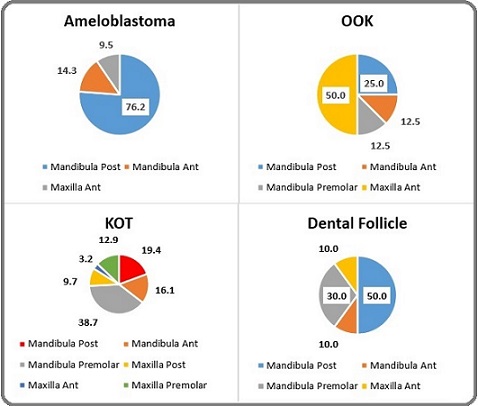

The overall distribution of dental follicle localizations is visualized in Figure 2, highlighting the predominant sites of involvement.

Figure 2. Distribution of Dental Follicle Cases According to Anatomical Localization .

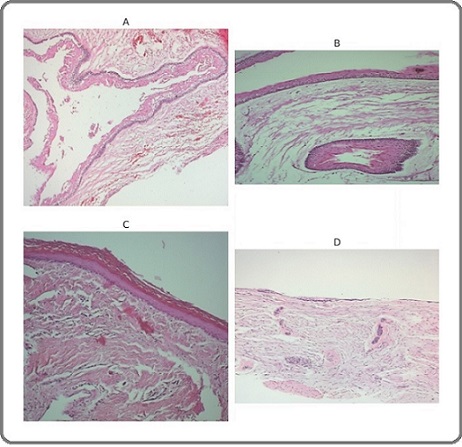

Representative histopathological features are shown in Figures 3A–D, including unicystic ameloblastoma (Figure 3A), keratocystic odontogenic tumor (Figure 3B), orthokeratinizing odontogenic keratocyst (Figure 3C), and odontogenic epithelial rests in dental follicle tissue (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Histopathological Features of Odontogenic Lesions: unicystic ameloblastoma, keratocystic odontogenic tumor (KOT), orthokeratinizing odontogenic keratocyst (OOK), and dental follicle tissue (H and E)..

Histopathological evaluation of ameloblastomas revealed marked architectural heterogeneity: 5 cases showed solid tumor islands, whereas 16 cases demonstrated unicystic morphology with luminal, intraluminal, or mural proliferation (Figures 3A–D).

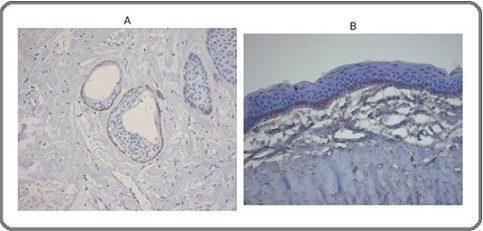

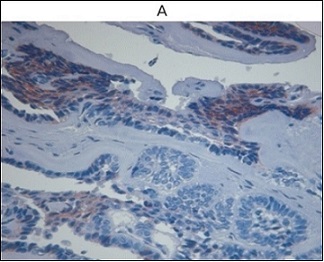

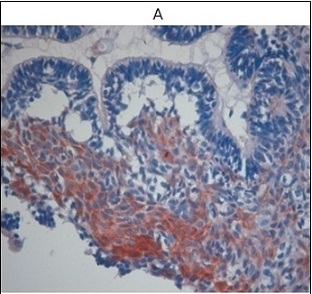

Integrin-β1 expression demonstrated a clear gradation among the lesions. Ameloblastomas exhibited weak, focal, or discontinuous basal-layer staining, whereas keratocystic odontogenic tumors showed more distinct and continuous basal positivity. Orthokeratinizing odontogenic keratocysts demonstrated intermediate staining intensity, while dental follicle tissues displayed uniformly preserved expression (Figures 4A and 4B).

Figure 4. Integrin β-1 Expression in Odontogenic Lesions (IHC). A Ameloblastoma showing weak, discontinuous basal-layer integrin-β1expression. B Keratocystic odontogenic tumor demonstrating continuous basal-layer integrin-β1positivity.

Quantitative analysis confirmed that integrin-β1 levels in ABL and KOT were significantly lower than in DF (p= 0.018 and p = 0.027, respectively).

E-cadherin expression differed markedly across the study groups. Only 33% of ameloblastoma cases showed preserved membranous staining (mean H-score 0.71; Figure 5A), whereas positivity rates were higher in keratocystic odontogenic tumors and orthokeratinizing odontogenic keratocysts (64% and 62.5%, respectively), with mean H-scores of 1.42 and 3.50 (Figures 5B and 5C). Dental follicle tissues retained strong, uninterrupted membranous E-cadherin expression (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. E-cadherin Expression in Ameloblastoma (IHC).

Comparative analysis demonstrated significantly reduced E-cadherin expression in ameloblastoma compared with dental follicles (p = 0.011) and in KOT compared with dental follicles (p = 0.034).

Snail expression demonstrated the greatest variability. Snail positivity in ameloblastoma was associated with higher immunoreactive scores, whereas KOT showed only rare weakly positive cases and OOK demonstrated complete absence of Snail expression. Dental follicle samples exhibited focal Snail positivity, reflecting physiological epithelial–mesenchymal interactions during odontogenesis. Snail positivity was detected in 42.9% of ABL cases, compared with only 3.2% positivity in KOT, and complete absence in OOK. DF samples showed Snail expression in 50% of cases. Snail expression in ABL was significantly higher than in both KOT and OOK (p = 0.009 and p = 0.005, respectively). Representative Snail staining is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Snail Expression in Ameloblastoma (IHC).

Twist expression was observed in 61% of ABL cases (mean H-score 0.81), 41.9% of KOT, 50% of OOK, and 50% of DF samples. Mean Twist H-scores were comparable across all groups, and no statistically significant intergroup differences were detected (p = 0.64), indicating that Twist may reflect a generalized regulatory role in epithelial–mesenchymal plasticity rather than serving as a discriminative marker of lesion aggressiveness. Representative Twist immunoreactivity is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Immunohistochemical Expression of Twist in Ameloblastoma..

Correlation analysis revealed no statistically significant associations among Twist, Snail, and E-cadherin expression levels (p > 0.05), indicating largely independent expression patterns of these markers. In addition, no statistically significant differences were observed between solid and unicystic ameloblastoma subtypes with respect to integrin-β1, E-cadherin, Snail, or Twist expression (p > 0.05).

Discussion

The present study provides an expanded comparative analysis of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)– related molecules in ameloblastoma, KOT, OOK, and dental follicle tissues. EMT is recognized as a key biological process contributing to tumor invasion, reduced intercellular adhesion, and the acquisition of mesenchymal properties, as described in both classical and contemporary EMT frameworks [1–4, 15]. Within odontogenic pathology, interest in EMT has increased considerably, although existing evidence remains fragmented and limited [16, 17]. Importantly, the inclusion of semi-quantitative H-score assessment in the present study allows the interpretation of EMT not only as a qualitative phenomenon but also as a graded biological continuum. The progressive changes in H-scores observed across the analyzed lesions support the concept of an EMT gradient rather than a binary epithelial–mesenchymal switch.

In this study, the transcription factor Snail emerged as the most discriminative EMT-associated marker. Snail is a well-known repressor of E-cadherin and a potent EMT inducer [10, 15], and its elevated expression in ameloblastoma aligns with previous findings showing that Snail overexpression enhances invasiveness in odontogenic tumors [12, 13, 19]. The near absence of Snail in OOK and minimal expression in KOT indicate fundamental biological differences between these entities, supporting the concept that parakeratinizing and orthokeratinizing cysts follow distinct developmental pathways [10, 12, 14]. Snail positivity in DF is expected, as EMT factors participate in physiological epithelial– mesenchymal interactions during odontogenesis [6, 7].

From a quantitative perspective, higher Snail- associated immunoreactivity in ameloblastoma, reflected by increased H-scores in positive cases, places this lesion at the mesenchymal end of the EMT spectrum, whereas OOK occupies the epithelial extreme with complete absence of Snail expression. KOT demonstrates an intermediate position, consistent with partial or incomplete EMT activation.

Reduced E-cadherin expression in ameloblastoma represents another important observation. Loss of E-cadherin is a well-established hallmark of EMT and is associated with diminished epithelial cohesion and enhanced cellular migration [5, 10, 16]. Previous studies of ameloblastoma similarly reported E-cadherin disruption, supporting its contribution to the infiltrative behavior of the tumor [16, 18]. By contrast, OOK preserved strong E-cadherin expression, consistent with its less aggressive clinical behavior. These differences reflect broader EMT patterns described in epithelial tumors of various origins [8, 9, 15].

The stepwise increase in E-cadherin H-scores from ameloblastoma to KOT and OOK further supports the presence of a biological EMT gradient. Low mean E-cadherin scores in ameloblastoma reflect weakened intercellular adhesion and enhanced plasticity, whereas high scores in OOK indicate preservation of epithelial integrity.

Twist expression showed a more uniform distribution across lesions. Although Twist is a canonical EMT driver activated under hypoxic conditions, including within tumor microenvironments [10, 15], the lack of intergroup differences suggests a more nonspecific regulatory role rather than a determinant of aggressiveness in odontogenic tumors. Twist positivity in DF further reflects its involvement in early tissue development and remodeling [1, 6, 16]. Several studies have suggested that Twist may act synergistically with other EMT factors, and thus its isolated evaluation may underestimate its biological relevance [10, 15].

Consistent mean Twist H-scores across all groups suggest that Twist expression alone does not define EMT positioning along the epithelial–mesenchymal axis in odontogenic lesions, but may instead represent a permissive or background regulatory signal within epithelial tissues.

Although elevated Snail expression and reduced E-cadherin levels in ameloblastoma may suggest a shift toward an EMT-like phenotype, these observations remain interpretive. The present study is based solely on immunohistochemical evaluation and does not provide direct mechanistic or molecular evidence confirming the functional involvement of Snail or Twist in tumor aggressiveness. Therefore, any proposed association between these transcription factors and the invasive behavior of ameloblastoma should be regarded as a hypothesis rather than an established causal mechanism. Further molecular validation, including gene-expression profiling, pathway activation assays, and functional in vitro modeling, is required to clarify their biological roles. Recent advances in EMT biology further contextualize our findings. Contemporary models describe EMT not as a binary switch but as a spectrum of intermediate and hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal states regulated by multilayered networks [15, 16]. Critical among these regulators are the transcription factors ZEB1 and ZEB2, which function in parallel with Snail and Twist and are tightly controlled by epithelial microRNA signatures particularly the miR- 200 and miR-34 families. Downregulation of miR-200 derepresses ZEB1/2 and suppresses E-cadherin, stabilizing partial EMT states [16, 19]. Although ZEB1/2 were not assessed in this study, the reduced E-cadherin expression in ameloblastoma is consistent with this regulatory axis.

The TGF-β pathway remains the most potent inducer of EMT in both developmental and pathological contexts. TGF-β/Smad signaling directly activates Snail, Twist, and ZEB transcription factors while simultaneously suppressing epithelial adhesion molecules [15, 20]. Recent transcriptomic studies of odontogenic tumors have demonstrated upregulation of TGF-β–responsive genes in ameloblastoma, suggesting that EMT activation may reflect upstream pathway modulation rather than isolated transcription factor changes [21, 22]. Similarly, studies published between 2021 and 2024 show that odontogenic tumors often exhibit partial EMT, characterized by the simultaneous retention of epithelial markers and acquisition of mesenchymal traits consistent with our observation of incomplete Twist suppression and variable Snail distribution.

Downregulation of integrin-β1 in ameloblastoma and KOT provides further insight into cell–matrix adhesion mechanisms. Integrins regulate interactions with the extracellular matrix and modulate signaling pathways that govern cell migration and proliferation [8]. Reduced β1-integrin expression has been associated with increased invasiveness in multiple tumor types [8, 9, 15]. Prior studies of odontogenic tumors have reported altered integrin expression, particularly in more aggressive ameloblastomas [16]. Preserved integrin expression in OOK aligns with its stable epithelial phenotype and supports the emerging concept of OOK as a biologically distinct entity [13, 21].

The parallel reduction of integrin-β1 and E-cadherin H-scores in ameloblastoma further strengthens the interpretation of EMT as a coordinated, multi-marker gradient affecting both cell–cell and cell–matrix adhesion systems.

Overall, the findings demonstrate marked heterogeneity in EMT activation across odontogenic lesions. Ameloblastoma exhibits the most consistent EMT profile, characterized by Snail upregulation, loss of E-cadherin, and reduced integrin-β1 expression, which corresponds to its clinically infiltrative behavior [12, 17, 23]. KOT demonstrates partial EMT features, whereas OOK largely maintains an epithelial phenotype. Together, the quantitative H-score patterns position these lesions along a continuum of EMT activation, with ameloblastoma at the mesenchymal-shifted end, OOK at the epithelial end, and KOT representing an intermediate biological state. These patterns correspond to broader EMT principles in which transcription factors, adhesion molecules, and extracellular matrix components collectively influence invasive potential [1, 4, 6, 19, 24].

The limitations of this study include the use of archival material, the semi-quantitative nature of immunohistochemistry, and the absence of molecular validation. Future investigations should incorporate functional assays assessing cell migration and invasion, advanced in vivo or three-dimensional organoid models, and emerging technologies such as spatial transcriptomics to better resolve intralesional EMT heterogeneity and microenvironmental interactions. In addition, integration of ZEB1/ZEB2 expression analysis and EMT-regulating microRNAs, particularly the miR-200 and miR-34 families, into future experimental designs may provide a more comprehensive understanding of regulatory EMT networks in odontogenic lesions. Future research using quantitative PCR, digital morphometry, and single-cell phenotyping may offer deeper insights into EMT heterogeneity in odontogenic tumors [19-21]. Nonetheless, the comparative EMT profiling presented here enhances current understanding of tumor biology and may contribute to improved diagnostic stratification and the development of targeted therapeutic strategies.

In conclusion, this comparative immunohistochemical analysis demonstrates that epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)–related markers exhibit distinct and graded expression patterns across odontogenic lesions. Ameloblastomas displayed the most pronounced EMT- associated profile, characterized by increased Snail expression together with reduced levels of the adhesion molecules E-cadherin and integrin-β1, whereas KOT showed intermediate features and OOK largely preserved an epithelial phenotype. Although Twist expression was detected across all lesion types, no statistically significant intergroup differences were observed, indicating that Twist alone is unlikely to determine lesion aggressiveness. Instead, the combined pattern of Snail upregulation and progressive loss of adhesion-related markers more accurately reflects EMT-associated biological behavior along a continuum of epithelial–mesenchymal plasticity. These findings underscore the heterogeneous and multifactorial nature of EMT activation in odontogenic lesions and highlight the need for further molecular and functional studies to clarify the mechanistic contribution of specific EMT regulatory pathways.

Conflict of Interest

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g., consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article. The authors declare no conflict of interest

Financial support

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition Kalluri R, Weinberg RA . Journal of Clinical Investigation.2009;119(6). CrossRef

- Mesenchymal to Epithelial Transition in Development and Disease Chaffer CL , Thompson EW , Williams ED . Cells Tissues Organs.2007;185(1-3). CrossRef

- Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis Zeisberg EM , Tarnavski O, Zeisberg M, Dorfman AL , McMullen JR , Gustafsson E, Chandraker A, et al . Nature Medicine.2007;13(8). CrossRef

- Alveolar epithelial cell mesenchymal transition develops in vivo during pulmonary fibrosis and is regulated by the extracellular matrix Kim KK , Kugler MC , Wolters PJ , Robillard L, Galvez MG , Brumwell AN , Sheppard D, Chapman HA . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.2006;103(35). CrossRef

- Epithelial–mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression Thiery JP . Nature Reviews Cancer.2002;2(6). CrossRef

- Differences in gene expression levels between early and later stages of human lung development are opposite to those between normal lung tissue and non-small lung cell carcinoma Kopantzev EP , Monastyrskaya GS , Vinogradova TV , Zinovyeva MV , Kostina MB , Filyukova OB , Tonevitsky AG , Sukhikh GT , Sverdlov ED . Lung Cancer.2008;62(1). CrossRef

- The epithelial–mesenchymal transition: new insights in signaling, development, and disease Lee JM , Dedhar S, Kalluri R, Thompson EW . The Journal of Cell Biology.2006;172(7). CrossRef

- SnapShot: The Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Sleeman JP , Thiery JP . Cell.2011;145(1). CrossRef

- Cancer Invasion and the Microenvironment: Plasticity and Reciprocity Friedl P, Alexander S. Cell.2011;147(5). CrossRef

- Inflammation: A driving force speeds cancer metastasis Wu Y, Zhou BP . Cell Cycle.2009;8(20). CrossRef

- Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A. Nature Reviews Cancer.2007;7(6). CrossRef

- TWIST activation by hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1): Implications in metastasis and development Yang M, Wu K. Cell Cycle.2008;7(14). CrossRef

- Unicystic Ameloblastoma: A Clinicopathologic Study of 33 Chinese Patients Li T, Wu Y, Yu S, Yu G. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology.2000;24(10). CrossRef

- Keratocystic odontogenic tumour: reclassification of the odontogenic keratocyst from cyst to tumour Madras J, Lapointe H. Texas Dental Journal.2008;125(5).

- WHO classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of head and neck tumors. Lyon: IARC Press Barnes L, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors . 2005;:430.

- Scaling and root planing vs modified Widman flap in chronic periodontitis Güllü C., Ozmeriç N., Tokman B.. J Periodontal Res.2005;40(2). CrossRef

- Aberrant Notch1/numb/snail signaling in adenomyosis Qi S., Zhao X., Li M.. Reprod Biol Endocrinol.2015;13(96). CrossRef

- Expression of integrin subunits in ameloblastoma Modolo F., Martins M.T., Loducca S.V., Araújo V.C.. Oral Dis.2004;10(5). CrossRef

- Laminin-5 γ2 chain colocalized with MMP-2 and MMP-13 in odontogenic keratocysts Wahlgren J., Väänänen A., Teronen O.. J Oral Pathol Med.2003;32(2). CrossRef

- Molecular mechanisms of EMT Lamouille S., Xu J., Derynck R.. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.2014;15(3).

- Guidelines for research on EMT Antin P. J , Berx G . Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.2020;21(6). CrossRef

- Odontogenic tumor markers - an overview Premalatha B. R., Patil S, Rao RS , Reddy NP , Indu M.. Journal of international oral health: JIOH.2013;5(2).

- Significance and prognostic value of Gli-1 and Snail/E-cadherin expression in progressive gastric cancer Wang Z, Shen Y, Li X, Zhou C, Wen Y, Jin Y, Li J. Tumor Biology.2014;35(2). CrossRef

- The ZEB/miR‐200 feedback loop—a motor of cellular plasticity in development and cancer? Brabletz S, Brabletz T. EMBO reports.2010;11(9). CrossRef

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright

© Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Biology , 2026

Author Details