Correlation between Awareness of Breast Cancer and Breast Health Awareness among Rural Women: A Cross-Sectional Study

Download

Abstract

Introduction: Breast cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer death in women. Breast health awareness through conducting breast self-examination at home, can help women identifying any changes in their breast and thereby it is beneficial for early detection and timely treatment breast cancer. This study aims to identify the correlation between awareness of breast cancer and breast health awareness among women living in rural areas.

Materials and methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted on 309 women living in three rural areas in Hai Duong province, Viet Nam by a stratified random sample method. The study questionnaire included awareness of breast cancer, knowledge about breast cancer prevention, and a checklist of women’s breast health awareness. Descriptive statistics and logistic regression were used for data analysis.

Results: The study found that most rural women have negative level of breast health awareness (82.5%), and most have low level of knowledge about breast cancer prevention. Perceived benefits of breast health awareness (p<0.001), perceived barriers to breast health awareness (p=0.033), and self-efficacy behind breast health awareness (p=0.001) were factors that affected women’s breast health awareness.

Conclusion: The study highlights the need for educational community programs, which should focus on increasing breast cancer awareness and breast health awareness for rural women.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and one of the leading causes of cancer death in women worldwide [1, 2]. In 2020, an estimated 4.4 million women died of cancer, of which breast cancer accounted for nearly 25% [3]. In Vietnam, breast cancer is also a public health problem because it is the most common cancer in women, with an average of more than 15.230 newly diagnosed women and more than 6.100 deaths each year [4]. According to the shift in population structure, Vietnam is showing an aging trend, along with changes in lifestyle, breast cancer is predicted to be the cancer with the highest incidence in women by 2025 [5].

Breast cancer survival varies between countries, with nearly 80% of deaths occurring in low- and middle-income countries [6]. Most women with breast cancer in Vietnam are diagnosed at a late stage, about 49.5% [7]. The 5-year survival rate of breast cancer patients is lowest in the late stage, but if detected and treated early, the cost is only about 20% compared to the late stage and nearly 100% of patients have a survival time of more than 5 years [8, 9]. Therefore, early detection of breast cancer is extremely important, it not only increases the survival and cure rate but also reduces the time and cost of treatment, thereby improving the quality of life for patients [7], [10].

Breast awareness is a concept where a woman is familiar with her breasts to detect any changes that may appear and proactively examines them, while breast self-examination is the monthly palpation of the breasts in a specific way that women are instructed to do. In most women of all ages, breast cancer causes fear, confusion, and anxiety [11]. These feelings are heightened by breast pain, asymmetry, discharge, lumps or thickenings, and a family history of positive breast cancer screening. Although concerns about breast health are well-documented, awareness of healthy breast characteristics, or more precisely, breast health awareness, is often lacking among women [11]. Therefore, early detection of breast cancer depends heavily on breast health awareness, which is why breast heath awareness should be included in general breast health education.

In recent years, many factors were found to be affect breast health awareness of women, but none of them concerned about the correlation between awareness of breast cancer and breast health awareness of women. Besdides, the Health Belief Model introduced by Champion in 1980 could be used to detect this relationship. The authors noted that when a woman is susceptible to breast cancer (perceived likelihood of the disease) and perceives the threat of the disease to her health (perceived severity), and also knows the benefits of screening methods (perceived benefits) rather than its barriers (perceived barriers), women are more likely to proactively perform breast self-examination at home, thereby improving their awareness of breast health [12]. With the main focus of breast cancer prevention programs focusing on early detection and screening to reduce mortality, a special center of attention is placed on breast health awareness. This study was conducted to 1) describe the awareness of breast cancer and breast health among rural women, and 2) identify the correlation between awareness of breast cancer and breast health awareness among these participants.

Materials and Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional study was conducted three rural areas in Hai Duong province, Viet Nam from October 2021 to December 2022, and this study was in accordance with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) checklist (https://www.strobe- statement.org/).

Sample/Participants

The number of participants was calculated based on the formula:

n= Z21-α/2. p (1-p)/ (pε)2

n: sample size

p: the rate of breast health awareness with the positive result; in this study, p = 0.158 [13].

α: Statistical significance level with α = 5% then coefficient Z1-α/2 = 1.96

ε: relative error between the experimental study and the population proportion (ranges from 0.1 - 0.5). The study took ε = 0.27

Applying those results, the sample size was 280. However, to increase the representativeness of the study population, the research team took an additional 10% of the calculated sample size. Therefore, the final sample size obtained was 309 women.

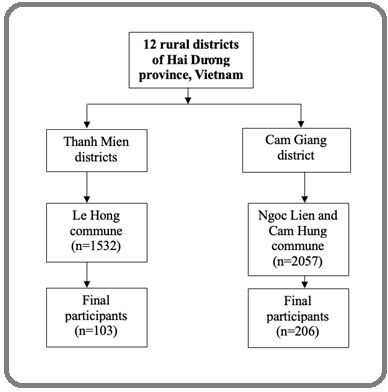

A stratified random sample of rural women was recruited (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Participant’s selection.

Inclusion criteria: rural women aged around 20-59 year old; not pregnant and not breastfeeding; able to speak, read, listen and understand Vietnamese; and volunteer to participate in the study. While, exclusion criteria included women with being diagnosed with breast cancer or were in the advanced stages of the disease.

Accordingly, after obtaining the sample size, the research team compiled a list and numbered all eligible women in each commune. This list was obtained from the Commune Women’s Union and the Commune Health Station. Then, the research team used Excel software to randomly select 103 women in each commune to send invitation letters to participate in the study.

Data collection

The questionnaire included three parts.

Part 1: Demographic information of the participants included age, education level, marital and occupational status, family history of breast cancer and other cancers. Part 2: Breast cancer awareness was measured by the Health Belief Model scale developed by Champion V [12]. The scale consisted of 6 subscales with a total of 42 items, including Perceived susceptibility to breast cancer (5 items); Perceived seriousness to breast cancer (7 items); Perceived benefits of breast self-examination (6 items); Perceived barriers to breast self-examination (6 items); Health motivation behind breast self-examination behavior (7 items); and Self-efficacy behind breast self- examination behavior (11 items). All items are based on a 5-point Likert scale with “5 - Strongly agree” to “1 - Strongly disagree”, then the total score of each subscale was counted. All participants were invited into a large meeting room of the health station, where they were given a paper questionnaire and had 20 minutes to complete it. The distance between each person was one meter to limit the communication which could affect the survey results. The final result of each subscale was divided to “Yes” if the total score of Perceived susceptibility to breast cancer ≥15 points; Perceived seriousness to breast cancer ≥21 points; Perceived benefits of breast self-examination ≥18 points; Perceived barriers to breast self-examination ≥18 points; Health motivation behind breast self-examination behavior ≥21 points; and Self-efficacy behind breast self- examination behavior ≥33; while “No” for under those scores [14]. Champion was the first author to conduct studies on the reliability and validity of this scale with Cronbach’s α coefficients reaching from 0.69-0.9 for the sub-scales. The results of the repeated test after 2 weeks showed statistical significance > 0.7 [15]. For the Vietnamese version used in this study, we conducted a pilot test with 60 women and 5 experts. The results showed that the scale had good content validity, with the score (I-CVI) for all 42 items being >0.79. The internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha for the 6 subscales ranged from 0.72 to 0.86.

Part 3: Knowledge about breast cancer prevention included 04 questions: the need for breast self-examination, the appropriate timing for breast self-examination, the need for breast cancer screening, and the need for regular breast cancer screening.

Part 4: Breast health awareness of rural women was assessed by the checklist (under direct observation by 12 obstetric nurses who attended two separate training sessions by obstetrician on the procedure and how to assess patients’ breast self-examination skills) was developed based on the cancer communication doccument of the Vietnamese Ministry of Health [16]. The checklist consists of 9 items, specifically, from the items 1 to 8 to evaluate the implementation technique, while item 9 records the participants’ self-examination results. Step 9 was used to compare with the doctor’s clinical examination results and was not counted in the total practice score. Each correct practice step awarded 1 point and 0 point for incorrect. Accordingly, the results of awareness level classification were “Possitive” if the total score was over 8.5 points, and “Negative” with under 8.5 points. After completing the assessment checklist, research team asked for comments from 5 experts in the clinical and training fields in developing the practice process checklist and received high consensus.

Ethical Considerations

The study was reviewed and approved by the Scientific and Ethics Council of Nam Dinh University of Nursing in Decision No. 2765/GCN-HDDD dated October 2021. All participants were informed about the purpose and content of the study; and if they agreed, they were asked to sign a consent form before accessing the questionnaire. They have the right to withdraw from the study whenever they want. The study does not interfere with the health or life of the participants.

Bias

To minimize recall errors (due to participants not remembering the number of times they self-examined, having had a breast examination, etc.) and random errors (due to research subjects being afraid to answer and practicing self-examination incorrectly or exchanging information with each other during the questionnaire filling process), the researchers thoroughly trained the investigators, directly supervised the investigation process, and collected data; as well as arranged seating to avoid exchanges as well as being ready to support and explain when needed. In addition, the study also checked the validity and reliability of the questionnaires before use to reduce measurement bias.

Data analysis

data. Descriptive statistics were used to describe variables.Additionally, the Chi-square test was used to test the difference between variables in breast cancer awareness and breast health awareness of rural women. A logistic regression model was used to investigate the predictive ability of breast cancer awareness related to breast health awareness. The significance level with p<0.05 was considered to have a difference/relationship between variables.

Results

General characteristic of rural women

Among 309 rural women who participated in the study, their average age was around 45.2 ± 8.4, with 94.5% getting married and 75.1% not graduating from high school. In addition, nearly half of the participants were farmers (46.9%), and 3.9% had a family history of breast cancer (Table 1).

| Contents | N=309 | % |

| Age (Mean; SD) | 45.2 ± 8.4 | |

| Education level | ||

| Under high school | 232 | 75.1 |

| High school graduate or higher | 77 | 24.9 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 17 | 5.5 |

| Married | 292 | 94.5 |

| Employment | ||

| Farmer | 145 | 46.9 |

| Officer | 72 | 23.3 |

| Worker | 57 | 18.4 |

| Others | 35 | 11.4 |

| Family history of breast cancer | ||

| Yes | 12 | 3.9 |

| No | 297 | 96.1 |

Status of breast cancer awareness among rural women

Table 2 indicated that 62.2% of rural women perceived that breast cancer is a serious disease, however only 25.6% perceived the benefits of breast self-examination at home.

| Breast cancer awareness among rural women | N=309 | % | |

| Perceived susceptibility to breast cancer | No (<15 points) | 249 | 80.6 |

| Yes (≥15 points) | 60 | 19.4 | |

| Perceived seriousness to breast cancer | No (<21 points) | 115 | 37.2 |

| Yes (≥21 points) | 194 | 62.8 | |

| Perceived benefits of breast health awareness | No (<18 points) | 230 | 74.4 |

| Yes (≥18 points) | 79 | 25.6 | |

| Perceived barriers to breast health awareness | No (<18 points) | 84 | 27.2 |

| Yes (≥18 points) | 255 | 72.8 | |

| Health motivation behind breast health awareness | No (<21 points) | 44 | 14.2 |

| Yes (≥21 points) | 265 | 85.8 | |

| Self-efficacy behind breast health awareness | No (<33 points) | 228 | 73.8 |

| Yes (≥33 points) | 81 | 26.2 |

However, most rural women (85.8%) were aware of the health motivations for breast self-examination, and a large proportion of participants (72.8%) perceived barriers to practicing breast self-examination. The percentage of women who were aware of self-efficacy behind breast self-examination behavior was low, at 26.2% (Table 2).

Knowledge of breast cancer prevention and Breast health awareness of rural women

Among 309 participants, most of them didn’t have a knowledge about breast cancer prevention, of which 70.6% indicated that no need to practice breast self-examination, and 81.2% didn’t know the appropriate timing for breast self-examination. Besides, only 20.1% agreed with the need for breast cancer screening, and 18.4% for the need of regular breast cancer screening (Table 3). For reast health awareness of rural women, the rate of participants having negative awareness was very high (82.5%) (Table 3).

| Contents | N | % | |

| Knowledge about breast cancer prevention | |||

| Do you need to practice breast self-examination at home? | Yes | 91 | 29.4 |

| No | 218 | 70.6 | |

| Should perform breast self-examination within 7-10 days after menstrual period? | Yes | 58 | 18.8 |

| No | 251 | 81.2 | |

| Should do breast cancer screening at medical facilities? | Yes | 62 | 20.1 |

| No | 247 | 79.9 | |

| Do you need to get screened for breast cancer frequently? | Yes | 57 | 18.4 |

| No | 122 | 39.5 | |

| Only go when having unusual signs | 130 | 42.1 | |

| Breast health awareness | |||

| Possitive | 54 | 17.5 | |

| Negative | 255 | 82.5 |

Correlation between breast cancer awareness and breast health awareness of rural women

The results of Table 4 indicated that three factors of breast cancer awareness, including realizing the benefits of breast health awareness (p<0.001), recognizing barriers to breast health awareness (p=0.030), and awareness of self-efficacy behind breast health awareness (p=0.001) were related to rural women’s breast health awareness (Table 4).

| Breast cancer awareness among rural women | Breast health awareness | p-value | ||||

| Negative | Positive | |||||

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Perceived susceptibility to breast cancer | No | 207 | 83.1 | 42 | 16.9 | 0.566 |

| Yes | 48 | 80 | 12 | 20 | ||

| Perceived seriousness to breast cancer | No | 101 | 87.8 | 14 | 12.2 | 0.059 |

| Yes | 154 | 79.4 | 40 | 20.6 | ||

| Perceived benefits of breast health awareness | No | 209 | 90.9 | 21 | 9.1 | 0.000** |

| Yes | 46 | 58.2 | 33 | 41.8 | ||

| Perceived barriers to breast health awareness | No | 63 | 75 | 21 | 25 | 0.030* |

| Yes | 192 | 85.3 | 33 | 14.7 | ||

| Health motivation behind breast health awareness | No | 40 | 90.9 | 4 | 9.1 | 0.114 |

| Yes | 215 | 81.1 | 50 | 18.9 | ||

| Self-efficacy behind breast health awareness | No | 198 | 86.8 | 30 | 13.2 | 0.001** |

| Yes | 57 | 70.4 | 24 | 29.6 |

Chi-square test; Significant difference of values is indicated by *p < 0.05 and **p ≤ 0.001

Accordingly, the logistic regression model results in Table 5 showed that women with high perceived benefits of breast health awareness were 7.1 times more likely to practice breast self-examination with passed results than women with no perceived benefits (p<0.001). Similarly, rural women with perceived barriers to breast health awareness were 1.9 times more likely to practice breast self-examination with passed results than women with no perceived barriers (p=0.033). Finally, participants with awareness of self-efficacy behind breast health awareness were 2.8 times more likely to practice breast self-examination with the passed result than women with no awareness of to self-efficacy (p=0.001) (Table 5).

| Breast cancer awareness among rural women | OR | CI (95%) | p-value |

| Perceived benefits of breast health awareness | 7.1 | 3.8-13.5 | 0 |

| Perceived barriers to breast health awareness | 1.9 | 1.1- 3.6 | 0.033 |

| Self-efficacy behind breast health awareness | 2.8 | 1.5 – 5.1 | 0.001 |

Logistic regression with χ2(3) = 229.6, Hosmer and Lemeshow test p=0.725>0.05. Nagelkerke R Square R2= 0.278

Discussion

The health belief model has shown that when someone believes that they are very likely to get a disease and perceive the seriousness of the disease, the benefits of health behavior that can prevent the disease, along with low barriers and high motivation and self-efficacy, they are more likely to perform that health behavior [17].

Our study found that the highest proportion of women were aware of the health motivation behind breast health awareness (85.8%), aware of barriers to breast health awareness (72.8%), and perceived seriousness of breast cancer (62.8%). This result is similar to some previous studies [18, 19].

Specifically, the rate of rural women aware of the seriousness of breast cancer was quite high (62.8%). This can be explained by the fact that currently, information related to cancer is widely disseminated, most rural households have access to the Internet and television, so it is understandable that women aware this issue. This result is also consistent with the 85.8% of participants who were aware of the health motivation behind breast health awareness. However, this result is in contrast to the very low rate (15.9%) of rural women who know that they need to performed breast self-examination at home and more than 70% of women participating in the study did not have knowledge about the necessary of breast self- examination or regular checkup breast cancer because they thought their chances of getting breast cancer were very low. This result is very worrying because the American Cancer Society predicted that one in eight women would be diagnosed with breast cancer at some point in their lives [19], while the Vietnamese Ministry of Health also listed breast cancer as one of the most common cancers in women [20]. Therefore, raising women’s awareness of the importance of breast health awareness at home and implementing training programs for women to self- examine their breasts is necessary.

Another result we found to explain the low practice of breast self-examination and regular breast self-examination in this study was that the percentage of women with perceived barriers to breast health awareness was very high (72.8%), while their confidence behind breast health awareness (26.2%) and perceived benefits of breast health awareness (25.6%) were very low. This result is quite similar to the study of Abolfotouh et al. [21] and the study of Didarloo et al. [22]. This is also completely consistent with the results of the Health Belief Model. Accordingly, people must be aware of the benefits of the breast health awareness, feel confident with the awareness, and encounter few barriers to be willing to adopt new awareness and change existing awareness [23]. These results provide an important basis for developing intervention programs that focus on analyzing and clarifying the role and benefits of breast health awareness in preventing and early detecting breast cancer, as well as supporting women to identify barriers and find appropriate solutions [24].

In addition, this study found that only 10.7% of participants had the positive awareness of breast health. This result was quite similar to the study of Pengpid and Peltzer in 24 countries in Asia, Africa, and the Americas [25], and the study of Tuyen et al. [26] and Nguyen &Vu in Vietnam [27], but lower than the study of Abolfotouh et al. [21] and Vo et al. [28]. The answers explained, for this reason, were that the participants were rural women, 75.1% of them graduated from secondary school or under, and up to 96.1% had no family history of breast cancer, so they were less interested in the behavior of practicing breast self-examination regularly at home. This result is evidence that developing an educational program on breast health awareness for rural women is really appropriate and necessary.

Regarding the relationship between rural women’s awareness of breast cancer and breast health awareness, our study showed that women with high perceived benefits of breast health awareness were 7.1 times more likely to practice breast health awareness with passed result than women with no perceived benefits (p<0.001). This result is similar to the study of Didarloo et al. (2017) in Iran, or the study of Dewi et al. (2019) in Indonesia [22],[29]. Perceived benefits mean positive results by avoiding exposure to disease. Specifically, the smallest suspicious tumor can be detected by monthly breast self-examination [11]. Self-efficacy is also a person’s belief in their ability to aware breast health successfully and accurately as well as their ability to self-detect suspicious tumors. Therefore, educational programs should focus on appropriate planning and training to increase women’s confidence and awareness of the benefits of breast health [23].

In addition, the results showed that participants in the group who perceived barriers to breast health awareness and those with awareness of self-efficacy behind breast health awareness were 1.9 times and 2.8 times more likely to aware of breast health with positive results than those with no awareness, respectively (p < 0.05). The results we found were quite similar to many previous studies, such as the study by Ahmadian et al. (2016) which also showed that high self-efficacy and low barriers were factors that not only predicted past breast health awareness but also predicted future breast health awareness intentions [30]. The study by Mousavi et al. (2018) suggested that all the constructs of the Health Belief Model could predict breast health awareness, among these constructs, perceived barriers were the most important predictors of the behavior [31]. This important result has helped the research team have a clear direction when building an educational intervention program on breast cancer awareness and breast health awareness instructions. Specifically, these programs need to focus on raising awareness of the benefits of breast health awareness, increasing self-efficacy, and reducing barriers to help participants increase their awareness about having breast health through practicing breast self-examination according to the steps recommended by the Ministry of Health, at the same time help women maintain this awareness in a sustainable way [32].

A limitation of this study is that it is only applied within the framework of the Health Belief Model structure, so it only focuses on examining the cognitive factors and personal beliefs that affect changes in breast health awareness, while some other social factors such as policies, resources, human resources, and facilities and equipment have not been fully considered. At the same time, the Health Belief Model is intuitive in nature, so it is widely used in community interventions targeting low-educated groups, this study only focuses on women in rural areas and has not been extended to women with higher education in urban or city areas.

This study is the basis for health care providers and community educators, especially community nurses, to develop and implement health education programs based on the Health Belief Model to raise awareness, remove barriers, and increase the rate of breast health awareness at home for rural women. In addition, the results are alsothe basis for professionals to integrate and proactively mention breast health awareness for women when they go for gynecological examinations and breast examinations at medical facilities. In terms of nursing training, the content of the Health Belief Model and the importance of breast health awareness should be included in the curriculum to help nursing students understand and support the community to effectively implement it.

The rate of rural women having breast health awareness with positive results was very low (17.5%). However, most rural women were aware of the health motivations for breast health awareness (85.8%), and perceived barriers to breast health awareness (72.8%). Perceived benefits of breast health awareness (p<0.001), perceived barriers to breast health awareness (p=0.033), and awareness of self-efficacy behind breast health awareness (p=0.001) were factors that affected women’s breast health awareness. Therefore, study highlights the need for educational community programs, which should focus on increasing breast cancer awareness and breast health awareness for rural women.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere thanks to the study participants for their enthusiastic cooperation.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest in this study.

References

- Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL , Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians.2021;71(3). CrossRef

- World Heaalth Organization (2021). Breast cancer now most common form of cancer: WHO taking action, available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/03-02-2021-breast-cancer-now-most-common-form-of-cancer-who-taking-action Accessed 4/11/2023.

- Global and regional estimates of orphans attributed to maternal cancer mortality in 2020 Guida F, Kidman R, Ferlay J, Schüz J, Soerjomataram I, Kithaka B, Ginsburg O, et al . Nature Medicine.2022;28(12). CrossRef

- Ministry of Health. National strategy for non-communicable disease prevention and control 2015-2025. Available at: https://vncdc.gov.vn/files/document/2016/4/chien-luoc-quoc-gia-phong-chong-benh-khong-lay-nhiem.pdf Accessed July 13, 2024.

- Projecting Cancer Incidence for 2025 in the 2 Largest Populated Cities in Vietnam Nguyen SM , Deppen S, Nguyen GH , Pham DX , Bui TD , Tran TV . Cancer Control: Journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center.2019;26(1). CrossRef

- World Health Organization. WHO launches new roadmap on breast cancer. Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/03-02-2023-who-launches-new-roadmap-on-breast-cancer. Accessed 4/11/2023 2023.

- Cancer Control in Vietnam: Where are we? - Cancer Control. Tran VT , Anh PT , Tu DV . 2016.

- Cost of treatment for breast cancer in central Vietnam Hoang Lan N, Laohasiriwong W, Stewart JF , Tung ND , Coyte PC . Global Health Action.2013;6. CrossRef

- Assessment of Factors Associated with Breast Self-Examination among Health Extension Workers in West Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia Azage M, Abeje G, Mekonnen A. International Journal of Breast Cancer.2013;2013. CrossRef

- Effects of Model-Based Interventions on Breast Cancer Screening Behavior of Women: a Systematic Review Saei Ghare Naz M, Simbar M, Rashidi Fakari F, Ghasemi V. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP.2018;19(8). CrossRef

- Breast cancer and breast health awareness as an evolving health promotion concept Plesnicar A., Kralj B., Kovac V.. 2004;38(1).

- The relationship of breast self-examination to health belief model variables Champion V. L.. Research in Nursing & Health.1987;10(6). CrossRef

- Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Regarding Breast Cancer Early Detection Among Women in a Mountainous Area in Northern Vietnam Toan DTT , Son DT , Hung LX , Minh LN , Mai DL , Hoat LN . Cancer Control: Journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center.2019;26(1). CrossRef

- Application of the Health Belief Model for Breast Cancer Screening and Implementation of Breast Self- Examination Educational Program for Female Students of Selected Medical and Non-Medical Faculties at Umm al Qura University" Mohamed H, Ibrahim Y, Lamadah S, Hassan M, El-Magd A. Life Science Journal.;13(5).

- Knowledge and practice of breast self-examination among women in Thuong Cat ward, Bac Tu Liem district, Hanoi Pham TQ , Pham VT , Tran MH , et al . J of Nurs Sci.2020;3(2):14-22. CrossRef

- Current status of breast self-examination of women in Tien Phuong commune Nguyen TDH , Vu TN . J Med Res.2020;8:144. CrossRef

- The health belief model. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice Glanz K, Rimer BK , Viswanath K. San Francisco, CA, US.2018;:94103-1741.

- Application of the Champion Health Belief Model to determine beliefs and behaviors of Turkish women academicians regarding breast cancer screening: A cross sectional descriptive study Kirag N, Kızılkaya M. BMC women's health.2019;19(1). CrossRef

- Effect of The Health Belief Model-Based Education on Preventive Behaviors of Breast Cancer Mahmoud AA ., Abosree TH , Aliem RSAE . Evidence-Based Nursing Research.2020;2(4). CrossRef

- Ministry of Health. Decision 1639/QD-BYT 2021 on promulgating the Supplementary Document on Guidelines for prevention, screening, and early detection of breast and cervical cancer in the community under Project 818 until 2030, issued on March 19, 2021. Available at: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/The-thao-Y-te/Quyet-dinh-1639-QD-BYT-2021-Tai-lieu-san-loc-ung-thu-vu-ung-thu-co-tu-cung-tai-cong-dong-468045.aspx Accessed July 13, 2024.

- Using the health belief model to predict breast self examination among Saudi women Abolfotouh MA , BaniMustafa AA , Mahfouz AA , Al-Assiri MH , Al-Juhani AF , Alaskar AS . BMC public health.2015;15. CrossRef

- Psychosocial predictors of breast self-examination behavior among female students: an application of the health belief model using logistic regression Didarloo A, Nabilou B, Khalkhali HR . BMC public health.2017;17(1). CrossRef

- Effects of Health Belief Model-Based Education on Health Beliefs and Breast Self-Examination in Nursing Students Kıssal A, Kartal B. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing.2019;6(4). CrossRef

- Breast cancer statistics, 2013 DeSantis C, Ma J, Bryan L, Jemal A. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians.2014;64(1). CrossRef

- Knowledge, attitude and practice of breast self-examination among female university students from 24 low, middle income and emerging economy countries Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP.2014;15(20). CrossRef

- Breast Self-Examination: Knowledge and Practice Among Female Textile Workers in Vietnam Tuyen DQ , Dung TV , Dong HV , Kien TT , Huong TT . Cancer Control: Journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center.2019;26(1). CrossRef

- Breast self-examination practices among women in Tien Phuong commune in 2020 Nguyen TDH , Vu TN . Medical Research Journal.2020;(8):229-235.

- Study on women's breast self-examination practices and related factors Vo TNH , Tran TT , Champion JD . Ho Chi Minh City Medicine.2016;5(20):244-254. CrossRef

- Determinants of breast self-examination practice among women in Surabaya, Indonesia: an application of the health belief model Dewi TK , Massar K, Ruiter RAC , Leonardi T. BMC public health.2019;19(1). CrossRef

- Psychosocial Predictors of Breast Self-Examination among Female Students in Malaysia: A Study to Assess the Roles of Body Image, Self-efficacy and Perceived Barriers Ahmadian M, Carmack S, Samah AA , Kreps G, Saidu MB . Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP.2016;17(3). CrossRef

- The Efficacy of Clinical Breast Exams and Breast Self-Exams in Detecting Malignancy or Positive Ultrasound Findings Huang H, Chen L, He J, Nguyen Qd . Cureus.2022;14(2). CrossRef

- Health Beliefs as Predictors of Breast Self-Examination Behavior Mousavi F. International Journal of Women's Health and Wellness.2018;4(2). CrossRef

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Copyright

© Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Care , 2025

Author Details

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 0 times

- PDF (FULL TEXT) downloaded - 0 times

- XML downloaded - 0 times